- 1CAS Key Laboratory for Behavioral Science, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

1中国科学院心理研究所行为科学国家重点实验室,北京,中国 - 2Department of Psychology, University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

2中国科学院心理学部,北京,中国

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) has impacted society in many aspects. Alongside this progress, concerns such as privacy violation, discriminatory bias, and safety risks have also surfaced, highlighting the need for the development of ethical, responsible, and socially beneficial AI. In response, the concept of trustworthy AI has gained prominence, and several guidelines for developing trustworthy AI have been proposed. Against this background, we demonstrate the significance of psychological research in identifying factors that contribute to the formation of trust in AI. Specifically, we review research findings on interpersonal, human-automation, and human-AI trust from the perspective of a three-dimension framework (i.e., the trustor, the trustee, and their interactive context). The framework synthesizes common factors related to trust formation and maintenance across different trust types. These factors point out the foundational requirements for building trustworthy AI and provide pivotal guidance for its development that also involves communication, education, and training for users. We conclude by discussing how the insights in trust research can help enhance AI’s trustworthiness and foster its adoption and application.

人工智能(AI)的快速发展在许多方面影响了社会。随着这一进展,隐私侵犯、歧视性偏见和安全风险等问题也随之出现,突显了开发伦理、负责任和社会有益的人工智能的必要性。对此,可信赖人工智能的概念日益受到重视,并提出了若干开发可信赖人工智能的指导方针。在此背景下,我们展示了心理研究在识别影响对人工智能信任形成因素方面的重要性。具体而言,我们从三维框架(即信任者、受托者及其互动背景)的角度回顾了关于人际信任、人机信任和人机智能信任的研究发现。该框架综合了与不同信任类型相关的信任形成和维持的共同因素。这些因素指出了构建可信赖人工智能的基础要求,并为其发展提供了关键指导,同时也涉及用户的沟通、教育和培训。 我们最后讨论信任研究的见解如何帮助提高人工智能的可信度,并促进其采用和应用。

1 Introduction 1 引言

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the driving force behind industry 4.0 and has profoundly affected manufacturing, business, work, and our daily life (Magd et al., 2022). The invention of generative AI technologies, such as ChatGPT, marks a particularly significant leap in AI’s competence. While bringing significant changes to society, the development of AI has also sparked various concerns, including privacy invasion, hidden biases and discrimination, security risks, and ethical issues (Yang and Wibowo, 2022). One response to these concerns is the emergence of and emphasis on trustworthy AI that aims to strike a good balance between technological advancement and societal and ethical considerations (Li et al., 2023).

人工智能(AI)是工业 4.0 的驱动力,深刻影响了制造业、商业、工作和我们的日常生活(Magd et al., 2022)。生成性 AI 技术的发明,如 ChatGPT,标志着 AI 能力的一个特别重要的飞跃。在给社会带来重大变化的同时,AI 的发展也引发了各种担忧,包括隐私侵犯、潜在偏见和歧视、安全风险以及伦理问题(Yang and Wibowo, 2022)。对此的一个回应是出现并强调可信赖的 AI,旨在在技术进步与社会和伦理考量之间取得良好平衡(Li et al., 2023)。

Trustworthy AI, defined as AI that is lawful, ethical, and robust [High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG), 2019], represents a critical focus on responsible technology deployment. To develop trustworthy AI, multiple countries and international organizations have issued guidelines. For instance, the European Union issued the “Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI” in April 2019 (High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG), 2019); China published the “Governance Principles for a New Generation of Artificial Intelligence: Develop Responsible Artificial Intelligence” in June 2019 (National Governance Committee for the New Generation Artificial Intelligence, 2019); and on October 30, 2023, President Biden of the United States signed an executive order on the “safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of artificial intelligence” (The White House, 2023). These guidelines lay out requirements for the development of AI that ensure safety and protect privacy, enhance transparency and accountability, and avoid discrimination.

可信赖的人工智能被定义为合法、伦理和稳健的人工智能 [人工智能高级专家组(AI HLEG),2019],代表了对负责任技术部署的关键关注。为了发展可信赖的人工智能,多个国家和国际组织发布了指导方针。例如,欧盟在 2019 年 4 月发布了《可信赖人工智能伦理指南》(人工智能高级专家组(AI HLEG),2019);中国在 2019 年 6 月发布了《新一代人工智能治理原则:发展负责任的人工智能》(新一代人工智能国家治理委员会,2019);2023 年 10 月 30 日,美国总统拜登签署了一项关于“安全、可靠和可信赖的人工智能发展与使用”的行政命令(白宫,2023)。这些指导方针列出了确保安全、保护隐私、增强透明度和问责制、避免歧视的人工智能发展要求。

Trust and trustworthiness are key psychological constructs that have been extensively explored in research on interpersonal, human-automation, and human-AI trust, providing many insights on how a person or an agent can become trustworthy. The aforementioned guidelines primarily outline requirements for developers and providers of AI, but do not pay sufficient attention to how end-users may develop trust in AI systems. Research on trust specifies users’ expectations of AI, thus aiding the comprehension of their concerns and needs. It also assists in identifying which attributes of AI systems are crucial for establishing trust and improving their design. Furthermore, because trust has a significant impact on the adoption of AI, trust research may also help enhance the public’s acceptance and adoption of AI technology.

信任和可信性是关键的心理构念,在人际关系、人与自动化以及人与人工智能的信任研究中得到了广泛探讨,为理解一个人或代理如何变得可信提供了许多见解。上述指南主要概述了人工智能开发者和提供者的要求,但对最终用户如何建立对人工智能系统的信任关注不足。关于信任的研究明确了用户对人工智能的期望,从而有助于理解他们的担忧和需求。它还帮助识别哪些人工智能系统的属性对建立信任至关重要,并改善其设计。此外,由于信任对人工智能的采用有显著影响,信任研究也可能有助于提高公众对人工智能技术的接受度和采用率。

In this paper, we apply trust theories to the context of trustworthy AI, aiming to shed lights on how to create reliable and trustworthy AI systems. In doing so, this paper makes several notable contributions to the field of AI trust research. First, we systematically review research on interpersonal, human-automation, and human-AI trust by viewing the perception of AI from the perspective of social cognition (Frischknecht, 2021). It serves to validate and build upon theoretical frameworks in previous literature reviews and meta-analyses from a broader, more coherent, and more inclusive angle. Second, based on a three-dimension framework of trust that encompasses trustor, trustee, and their interactive context, we compile and summarize a large number of factors that may influence trust in AI by reviewing a wide range of empirical studies. Third, by identifying and consolidating these influencing factors, our paper offers guidance on enhancing AI trustworthiness in its applications, bridging theoretical concepts and propositions with practical applications.

在本文中,我们将信任理论应用于可信赖人工智能的背景,旨在阐明如何创建可靠和可信赖的人工智能系统。在此过程中,本文对人工智能信任研究领域做出了几项显著贡献。首先,我们从社会认知的角度系统回顾了人际信任、人机信任和人-人工智能信任的研究(Frischknecht, 2021)。这有助于验证并在更广泛、更连贯和更包容的角度上构建先前文献综述和元分析中的理论框架。其次,基于涵盖信任者、受托者及其互动背景的三维信任框架,我们通过回顾大量实证研究,汇编和总结了可能影响人工智能信任的众多因素。第三,通过识别和整合这些影响因素,本文为增强人工智能在应用中的可信赖性提供了指导,架起了理论概念和命题与实际应用之间的桥梁。

Overall, we aim to build a comprehensive framework for understanding and developing trustworthy AI that is grounded in end-users’ perspectives. Here, we focus primarily on the formation of trust, and do not distinguish between specific applications in automation or AI but refer to them collectively as automation or AI (Yang and Wibowo, 2022). The following sections are organized according to the three types of trust, ending with a discussion on the implications of trust research on enhancing trustworthy AI.

总体而言,我们旨在建立一个全面的框架,以理解和发展以最终用户的视角为基础的可信赖人工智能。在这里,我们主要关注信任的形成,并不区分自动化或人工智能的具体应用,而是将它们统称为自动化或人工智能(杨和维博沃,2022)。以下部分根据三种信任类型进行组织,最后讨论信任研究对增强可信赖人工智能的影响。

2 Interpersonal trust 人际信任

Rotter (1967) first defined interpersonal trust as the trustor’s generalized expectancy for the reliability of another person’s words or promises, whether verbal or written. This generalized expectancy, commonly known as trust propensity, is considered a personality characteristic that significantly influences actual behavior (Evans and Revelle, 2008). Trust typically arises in contexts characterized by risk and uncertainty. Mayer et al. (1995) framed interpersonal trust as a dyadic relationship between a trustor, the individual who extends trust, and a trustee, the entity being trusted, and treated trust as the willingness of the trustors to make themselves vulnerable despite knowing that the trustees’ actions could significantly impact them and irrespective of the trustors’ ability to monitor or control those actions. This section outlines critical factors that shape interpersonal trust.

罗特(1967) 首次将人际信任定义为信任者对另一个人言语或承诺(无论是口头还是书面)可靠性的普遍期待。这种普遍期待通常被称为信任倾向,被视为一种显著影响实际行为的人格特征(埃文斯和雷维尔,2008)。信任通常在风险和不确定性特征的环境中产生。梅耶等(1995) 将人际信任框架化为信任者(即扩展信任的个体)与受托者(即被信任的实体)之间的二元关系,并将信任视为信任者在知道受托者的行为可能对他们产生重大影响的情况下,愿意使自己处于脆弱状态的意愿,而不论信任者监控或控制这些行为的能力如何。本节概述了塑造人际信任的关键因素。

2.1 Characteristics of interpersonal trust

2.1 人际信任的特征

Trust is a term frequently encountered in daily life, characterized by a multitude of definitions and generally regarded as a multidimensional concept. McAllister (1995) identified two dimensions of interpersonal trust: cognitive and affective, while Dirks and Ferrin (2002) expanded this to include vulnerability and overall trust. Jones and Shah (2016) further categorized trust into three dimensions: trusting actions, trusting intentions, and trusting beliefs. Different theories capture distinct characteristics of trust but exhibit several key commonalities.

信任是日常生活中经常遇到的一个术语,具有多种定义,通常被视为一个多维概念。McAllister (1995) 确定了人际信任的两个维度:认知和情感,而 Dirks 和 Ferrin (2002) 将其扩展为包括脆弱性和整体信任。Jones 和 Shah (2016) 进一步将信任分类为三个维度:信任行为、信任意图和信任信念。不同的理论捕捉到信任的不同特征,但表现出几个关键的共性。

First, trust is dyadic, involving a trustor and a trustee, each with certain characteristics. From a dyadic perspective, interpersonal trust can be categorized into three types: reciprocal trust, highlighting the dynamic interactions between parties; mutual trust, reflecting a shared and consistent level of trust; and asymmetric trust, indicating imbalances in trust levels within interpersonal relationships (Korsgaard et al., 2015). The propensity to trust of the trustors exhibits significant individual differences, influenced by gender (Dittrich, 2015; Thielmann et al., 2020), age (Bailey et al., 2015; Bailey and Leon, 2019), and personality traits (Ito, 2022). Trust propensity influences trust at an early stage, and the assessment of the trustworthiness of trustees (trust beliefs) may ultimately determine the level of trust (McKnight et al., 1998).

首先,信任是双向的,涉及一个信任者和一个受托者,每个都有特定的特征。从双向的角度来看,人际信任可以分为三种类型:互惠信任,强调双方之间的动态互动;相互信任,反映出共享和一致的信任水平;以及不对称信任,表明人际关系中信任水平的不平衡(Korsgaard et al., 2015)。信任者的信任倾向表现出显著的个体差异,受性别(Dittrich, 2015; Thielmann et al., 2020)、年龄(Bailey et al., 2015; Bailey and Leon, 2019)和个性特征(Ito, 2022)的影响。信任倾向在早期阶段影响信任,而对受托者可信度的评估(信任信念)最终可能决定信任的水平(McKnight et al., 1998)。

Second, interpersonal trust can be influenced by interactive contexts, such as social networks and culture (Baer et al., 2018; Westjohn et al., 2022). The trustworthiness of strangers is frequently evaluated through institutional cues, including their profession, cultural background, and reputation (Dietz, 2011). Third, trust occurs within uncertain and risky contexts, and it is closely linked to risk-taking behavior (Mayer et al., 1995). Fourth, trust is usually dynamic. Trust propensity embodies a belief in reciprocity or an initial trust, ultimately triggering a behavioral primitive (Berg et al., 1995). Trustors will determine whether to reinforce, decrease, or restore trust based on the outcomes of their interactions with trustees. Individuals form expectations or anticipations about the future behavior of the trusted entity based on various factors, such as past experience and social influences. Thus, the trust dynamic is a process of social learning that often evolves gradually and changes with interactive experiences (Mayer et al., 1995).

其次,人际信任可以受到互动环境的影响,例如社交网络和文化(Baer et al., 2018; Westjohn et al., 2022)。陌生人的可信度通常通过制度线索进行评估,包括他们的职业、文化背景和声誉(Dietz, 2011)。第三,信任发生在不确定和风险的环境中,并与冒险行为密切相关(Mayer et al., 1995)。第四,信任通常是动态的。信任倾向体现了对互惠或初始信任的信念,最终触发一种行为原始冲动(Berg et al., 1995)。信任者将根据与受信者互动的结果来决定是加强、减少还是恢复信任。个人根据各种因素(如过去的经验和社会影响)形成对受信实体未来行为的期望或预期。因此,信任动态是一个社会学习的过程,通常是逐渐演变并随着互动经验而变化(Mayer et al., 1995)。

The above analysis shows that factors influencing interpersonal trust can be examined from three dimensions: the trustor, the trustee, and their interactive context. Interpersonal interactions correlate with changes in variables related to these three dimensions, ultimately leading to variations in the levels of trust and actual behavior.

上述分析表明,影响人际信任的因素可以从三个维度进行考察:信任者、受信者及其互动背景。人际互动与这三个维度相关的变量变化相关,最终导致信任水平和实际行为的变化。

2.2 Measurement of interpersonal trust

2.2 人际信任的测量

Trust, especially trust propensity, can be quantified using psychometric scales. These scales evaluate an individual’s specific trust or disposition toward trusting others via a set of questions (Frazier et al., 2013). Example items include, “I am willing to let my partner make decisions for me” (Rempel et al., 1985), and “I usually trust people until they give me a reason not to trust them” (McKnight et al., 2002). Meanwhile, economic games, such as trust game, dictator game, public goods game, and social dilemmas, provide a direct and potentially more accurate means to assess trust by observing individual actions in well-defined contexts (Thielmann et al., 2020). This approach is beneficial for deducing levels of trust from real decisions and minimizing the impact of social desirability bias (Chen et al., 2023). When integrated, behavioral observations from economic games and self-reported beliefs yield a more comprehensive perspective on trust by combining the strengths of observed actions and declared beliefs.

信任,特别是信任倾向,可以通过心理测量量表进行量化。这些量表通过一系列问题评估个体对他人的特定信任或信任倾向(Frazier et al., 2013)。示例项目包括:“我愿意让我的伴侣为我做决定”(Rempel et al., 1985),以及“我通常信任人们,直到他们给我一个不信任他们的理由”(McKnight et al., 2002)。与此同时,经济游戏,如信任游戏、独裁者游戏、公共物品游戏和社会困境,通过观察个体在明确情境中的行为,提供了一种直接且可能更准确的评估信任的方式(Thielmann et al., 2020)。这种方法有助于从真实决策中推导信任水平,并最小化社会期望偏差的影响(Chen et al., 2023)。当结合时,经济游戏中的行为观察和自我报告的信念通过结合观察到的行为和声明的信念的优势,提供了对信任的更全面的视角。

The aforementioned methods represent traditional approaches to assessing interpersonal trust. Alternative methods for measuring interpersonal trust also exist. To avoid redundancy, these methods are reviewed in the “Measurement of Trust in Automation” section.

上述方法代表了评估人际信任的传统方法。也存在其他测量人际信任的方法。为避免重复,这些方法将在“自动化中的信任测量”部分进行回顾。

3 Trust in automation 3 对自动化的信任

Trust extends beyond human interactions. Its importance is notable in interactions between humans and automated systems (Hoff and Bashir, 2015). According to Gefen (2000), trust in automation is the confidence, based on past interactions, in expecting actions from automation that align with one’s expectations and benefit oneself. In a similar vein, Lee and See (2004) characterize trust in automation as a quantifiable attitude that determines the extent of reliance on automated agents. Consequently, human-automation trust, akin to interpersonal trust, constitutes a psychological state that influences behaviors.

信任超越了人际互动。在人类与自动化系统之间的互动中,其重要性尤为显著(Hoff and Bashir, 2015)。根据Gefen (2000)的说法,对自动化的信任是基于过去互动的信心,期望自动化的行为与个人的期望一致并对自己有利。同样,Lee and See (2004)将对自动化的信任描述为一种可量化的态度,决定了对自动化代理的依赖程度。因此,人机信任类似于人际信任,构成了一种影响行为的心理状态。

Trust is crucial for the adoption of automation technologies, and a deficiency of trust in automation can lead to reduced reliance on these systems (Lee and See, 2004). Since the 1980s, with the widespread adoption of automation technology and its increasing complexity, research in human-automation interaction, technology acceptance models, and human-automation trust has drastically expanded. This section offers a brief overview of research in this field.

信任对于自动化技术的采用至关重要,而对自动化的信任不足可能导致对这些系统的依赖减少(Lee and See, 2004)。自 1980 年代以来,随着自动化技术的广泛采用及其复杂性的增加,人机自动化交互、技术接受模型和人机自动化信任的研究大幅扩展。本节将简要概述该领域的研究。

3.1 Automation 3.1 自动化

Automation usually refers to the technology of using devices, such as computers, to replace human execution of tasks in modern society, where automated technologies increasingly take over functions for efficiency, accuracy, and safety purposes (Kohn et al., 2021). Based on system complexity, autonomy, and necessary human intervention, automation can be divided into 10 levels, with level 0 signifying full manual control and level 10 denoting complete automation (Parasuraman et al., 2000). Furthermore, Parasuraman et al. (2000) identified four principal functions of automation within a framework of human information processing: information acquisition, information analysis, decision making, and action execution. An automation system may exhibit varying degrees of automation across these distinct functions.

自动化通常指的是在现代社会中使用设备(如计算机)来替代人类执行任务的技术,其中自动化技术越来越多地接管功能,以提高效率、准确性和安全性(Kohn et al., 2021)。根据系统复杂性、自主性和必要的人类干预,自动化可以分为 10 个级别,级别 0 表示完全手动控制,级别 10 表示完全自动化(Parasuraman et al., 2000)。此外,Parasuraman et al. (2000)在一个人类信息处理框架内识别了自动化的四个主要功能:信息获取、信息分析、决策和行动执行。一个自动化系统可能在这些不同功能中表现出不同程度的自动化。

The field of human-automation interaction has evolved alongside advances in computer technology, as reflected in the progress of its terminology: from HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) and HRI (Human-Robot Interaction) to HAI (Human-AI Interaction) (Ueno et al., 2022). Initially, research on automation trust was concentrated in sectors such as military, aviation, banking, and industrial manufacturing. With advancing computer technology, the focus of automation trust research has expanded to encompass office settings and the service sector. Furthermore, in the context of the internet, the pivotal importance of trust in the adoption of e-commerce, e-governance, and social media platforms has also been extensively investigated (Gefen, 2000; Featherman and Pavlou, 2003; Khan et al., 2014).

人机交互领域随着计算机技术的进步而发展,这在其术语的演变中得到了体现:从 HCI(人机交互)和 HRI(人机器人交互)到 HAI(人机智能交互)(Ueno et al., 2022)。最初,关于自动化信任的研究集中在军事、航空、银行和工业制造等领域。随着计算机技术的进步,自动化信任研究的重点已扩展到办公室环境和服务行业。此外,在互联网背景下,信任在电子商务、电子治理和社交媒体平台采纳中的关键重要性也得到了广泛研究 (Gefen, 2000; Featherman and Pavlou, 2003; Khan et al., 2014)。

3.2 Similarities between interpersonal trust and human-automation trust

3.2 人际信任与人机信任之间的相似性

Being a cornerstone of sustained human cooperation, trust is equally crucial to human-automation collaboration (Xie et al., 2019). Trust in humans and automation shares similarities, supported by both empirical and neurological evidence (Lewandowsky et al., 2000; Hoff and Bashir, 2015). For instance, a three-phase experiment study by Jian et al. (2000) that included tasks of word elicitation and meaning comparison showed that the constructs of trust in human-human and human-automation interactions are analogous. This resemblance may stem from the similar perceptions that individuals hold toward automated agents and fellow humans (Frischknecht, 2021).

作为持续人类合作的基石,信任对人机协作同样至关重要(Xie et al., 2019)。人类与自动化之间的信任有相似之处,这得到了实证和神经学证据的支持(Lewandowsky et al., 2000; Hoff and Bashir, 2015)。例如,Jian et al. (2000)进行的一项三阶段实验研究,包括词语引导和意义比较的任务,显示出人际互动和人机互动中的信任构念是相似的。这种相似性可能源于个体对自动化代理和同伴人类的相似认知(Frischknecht, 2021)。

Despite their non-human appearance, computers are often subject to social norms and expectations. Nass et al. (1997) demonstrated that assigning male or female voices to computers elicits stereotypical perceptions. In a similar vein, Tay et al. (2014) reported that robots performing tasks aligned with gender or personality stereotypes—such as medical robots perceived as female or extroverted, and security robots as male or introverted—received higher approval ratings. Moreover, studies in economic games like the ultimatum and public goods games have shown that people display prosocial behaviors toward computers, suggesting a level of social engagement (Nielsen et al., 2021; Russo et al., 2021).

尽管计算机看起来不像人类,但它们常常受到社会规范和期望的影响。Nass 等人 (1997) 证明,为计算机分配男性或女性声音会引发刻板印象的感知。同样,Tay 等人 (2014) 报告称,执行与性别或个性刻板印象相符的任务的机器人——例如被视为女性或外向的医疗机器人,以及被视为男性或内向的安全机器人——获得了更高的认可度。此外,在经济游戏如最后通牒游戏和公共物品游戏中的研究表明,人们对计算机表现出亲社会行为,这表明了一定程度的社会参与 (Nielsen 等人, 2021; Russo 等人, 2021)。

The Computers Are Social Actors (CASA) paradigm posits that during human-computer interactions, individuals often treat computers and automated agents as social beings by applying social norms and stereotypes to them (Nass et al., 1997). Such anthropomorphization usually happens subconsciously, leading to automated agents being perceived with human-like qualities (Kim and Sundar, 2012). In reality, intelligent devices exhibit anthropomorphism by mimicking human features or voices, setting them apart from traditional automation (Troshani et al., 2021; Liu and Tao, 2022). Although AI lacks emotions and cannot be held accountable for its actions, it is usually perceived through the lens of social cognition, making it difficult to regard AI as merely a machine or software; instead, AI is often viewed as an entity worthy of trust (Ryan, 2020).

计算机作为社会行为者(CASA)范式认为,在人机交互过程中,个体常常将计算机和自动化代理视为社会存在,通过对它们应用社会规范和刻板印象(Nass et al., 1997)。这种拟人化通常是潜意识中发生的,导致自动化代理被赋予类人特征(Kim and Sundar, 2012)。实际上,智能设备通过模仿人类特征或声音表现出拟人化,使其与传统自动化区分开来(Troshani et al., 2021; Liu and Tao, 2022)。尽管人工智能缺乏情感,且其行为无法被追责,但通常通过社会认知的视角来看待人工智能,这使得很难将人工智能仅仅视为机器或软件;相反,人工智能常常被视为值得信任的实体(Ryan, 2020)。

3.3 Importance of trust in automation

3.3 自动化中信任的重要性

Automation differs significantly from machines that operate specific functions entirely and indefinitely without human intervention (Parasuraman and Riley, 1997). For example, traditional vehicle components such as engines, brakes, and steering systems are generally regarded as highly reliable; in contrast, autonomous vehicles often evoke skepticism regarding their capabilities (Kaplan et al., 2021). While tasks performed by automation could also be executed by humans, the decision to rely on automation is contingent upon trust. For instance, individuals may refrain from using a car’s autonomous driving feature if they distrust its reliability. Moreover, the complexity of automation technologies may lead to a lack of full understanding by users (Muir, 1987), a gap that trust can help to bridge. Additionally, automation systems are also known to be particularly vulnerable to unexpected bugs (Sheridan, 1988), making the effectiveness of such systems heavily reliant on users’ trust in their performance (Jian et al., 2000).

自动化与完全独立且无限期运行特定功能的机器有显著不同,而无需人类干预(Parasuraman and Riley, 1997)。例如,传统的车辆组件如发动机、刹车和转向系统通常被认为是高度可靠的;相比之下,自动驾驶汽车常常引发对其能力的怀疑(Kaplan et al., 2021)。虽然自动化执行的任务也可以由人类完成,但依赖自动化的决定取决于信任。例如,如果个人不信任汽车的自动驾驶功能,他们可能会避免使用该功能。此外,自动化技术的复杂性可能导致用户缺乏充分理解(Muir, 1987),而信任可以帮助弥补这一差距。此外,自动化系统也被认为特别容易受到意外错误的影响(Sheridan, 1988),这使得此类系统的有效性在很大程度上依赖于用户对其性能的信任(Jian et al., 2000)。

Because of different individual understandings of automation and the complexity of automated systems, people may exhibit inappropriate trust in automation (Lee and See, 2004), which may lead to misuse or disuse. Misuse refers to the inappropriate use of automation, such as automation bias, that is, people relying on the recommendations of automated systems too much instead of exercising careful information search and processing. They may ignore information that contradicts the suggestions of the automation system, even if that information may be correct (Parasuraman and Manzey, 2010). Disuse refers to people refusing to use automation (Venkatesh et al., 2012). For instance, in decision-making tasks, algorithm aversion, which refers to skepticism toward algorithms, the core of automated systems, often takes place (Burton et al., 2020). The lack of public acceptance impedes advanced technology from achieving its full potential and practical application (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Similarly, inappropriate trust compromises the effectiveness of automated systems. Aligning the public’s trust level with the developmental stage of automation represents an ideal scenario. Thus, it is crucial to investigate the factors that shape trust in automation.

由于对自动化的不同个人理解以及自动化系统的复杂性,人们可能会对自动化表现出不恰当的信任(Lee and See, 2004),这可能导致误用或不使用。误用是指不恰当地使用自动化,例如自动化偏见,即人们过于依赖自动化系统的建议,而不是进行仔细的信息搜索和处理。他们可能会忽视与自动化系统建议相矛盾的信息,即使这些信息可能是正确的(Parasuraman and Manzey, 2010)。不使用是指人们拒绝使用自动化(Venkatesh et al., 2012)。例如,在决策任务中,算法厌恶,即对算法的怀疑,通常会发生,而算法是自动化系统的核心(Burton et al., 2020)。公众接受度的缺乏阻碍了先进技术实现其全部潜力和实际应用(Venkatesh et al., 2012)。同样,不恰当的信任也会影响自动化系统的有效性。 将公众的信任水平与自动化的发展阶段对齐代表了一个理想的情景。因此,调查影响对自动化信任的因素至关重要。

In human-automation trust, viewing trust as an attitude is widely accepted. However, in the context of interpersonal trust, the term attitude is not often used, whereas willingness is commonly employed. This distinction likely stems from technology acceptance theories, which posit that attitude shapes behavioral intentions and in turn influences actual behavior (Gefen et al., 2003). Hence, the importance of trust in automation is underscored by its effect on users’ behavior toward automated systems.

在人机信任中,将信任视为一种态度是广泛接受的。然而,在人际信任的背景下,态度这个术语并不常用,而意愿则被普遍使用。这一区别可能源于技术接受理论,该理论认为态度塑造行为意图,进而影响实际行为(Gefen et al., 2003)。因此,信任在自动化中的重要性通过其对用户对自动化系统行为的影响得到了强调。

3.4 Measurement of trust in automation

3.4 自动化信任的测量

Kohn et al. (2021) conducted a comprehensive review of methods for measuring human trust in automation, classifying these into self-reports, behavioral measures, and physiological indicators. Self-report methods typically involve questionnaires and scales, while behavioral measures include indicators like team performance, compliance and agreement rate, decision time, and delegation. Despite varied terminologies, these measures are based on the same principle: individuals demonstrating trust in an automation system are more inclined to follow its recommendations, depend on it, comply with its advice, lessen their oversight of the system, and delegate decision-making authority to it. Such behaviors are more evident when the automation system demonstrates high accuracy, potentially improving group performance. In dual-task situations, systems that are trusted usually result in faster decision-making and response times for ancillary tasks, whereas distrust can lead to slower responses.

Kohn 等人 (2021) 对人类对自动化信任的测量方法进行了全面的综述,将这些方法分为自我报告、行为测量和生理指标。自我报告方法通常涉及问卷和量表,而行为测量包括团队表现、合规性和一致性率、决策时间和委托等指标。尽管术语各异,这些测量基于相同的原则:对自动化系统表现出信任的个体更倾向于遵循其建议、依赖于它、遵从其建议、减少对系统的监督,并将决策权委托给它。当自动化系统表现出高准确性时,这种行为更为明显,可能会提高团队表现。在双任务情况下,受信任的系统通常会导致辅助任务的决策和响应时间更快,而不信任则可能导致响应变慢。

Physiological indicators include those from skin conductance, EEG (electroencephalography), fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), and fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy). A notable finding is that a reduction in skin conductance, suggesting lower cognitive load and emotional arousal, is associated with increased trust in automation (Khawaji et al., 2015). Moreover, employing methodologies like EEG, fMRI, and fNIRS to investigate the brain regions engaged in processing trust has demonstrated notable alterations (Ajenaghughrure et al., 2020).

生理指标包括皮肤电导、脑电图(EEG)、功能性磁共振成像(fMRI)和功能性近红外光谱(fNIRS)等。一个显著的发现是,皮肤电导的降低表明认知负荷和情感唤起较低,这与对自动化的信任增加有关(Khawaji et al., 2015)。此外,采用 EEG、fMRI 和 fNIRS 等方法研究处理信任的脑区已显示出显著的变化(Ajenaghughrure et al., 2020)。

Self-reporting methods, such as questionnaires measuring trust, capture static aspects of trust but cannot reflect its dynamic nature. Ayoub et al. (2023) introduced a dynamic measurement of trust during autonomous driving. Drivers’ physiological measures, including galvanic skin response, heart rate indices, and eye-tracking metrics, are recorded in real-time. Machine learning algorithms were then used to estimate trust based on these data. This real-time assessment of trust is critical for capturing its dynamic changes, thereby facilitating trust calibration.

自我报告方法,如测量信任的问卷,捕捉信任的静态方面,但无法反映其动态特性。Ayoub et al. (2023) 引入了在自动驾驶过程中对信任的动态测量。驾驶员的生理指标,包括皮肤电反应、心率指数和眼动追踪指标,实时记录。然后使用机器学习算法根据这些数据估计信任。这种对信任的实时评估对于捕捉其动态变化至关重要,从而促进信任的校准。

3.5 The relationship between automation and AI

3.5 自动化与人工智能的关系

3.5.1 AI: a next generation of automation

3.5.1 人工智能:下一代自动化

AI typically refers to the simulation of human intelligence by computers (Gillath et al., 2021). This simulation process encompasses learning (acquiring information and using it to acquire rules), reasoning (using rules to reach conclusions), and self-correction. In essence, AI represents a sophisticated form of automation, enhancing its domain and efficacy. In this paper, we refer automation as traditional automated technologies that are distinct from AI. The distinction lies in automation being systems that perform repetitive tasks based on static rules or human commands, while AI involves systems skilled in dealing with uncertainties and making decisions in novel situations (Cugurullo, 2020; Kaplan et al., 2021).

人工智能通常指的是计算机对人类智能的模拟(Gillath et al., 2021)。这一模拟过程包括学习(获取信息并利用这些信息来获取规则)、推理(使用规则得出结论)和自我纠正。实质上,人工智能代表了一种复杂的自动化形式,增强了其领域和效率。在本文中,我们将自动化定义为与人工智能不同的传统自动化技术。二者的区别在于,自动化是基于静态规则或人类指令执行重复任务的系统,而人工智能则涉及能够处理不确定性并在新情况中做出决策的系统(Cugurullo, 2020; Kaplan et al., 2021)。

Interestingly, in the initial research on human-automation interaction, AI was considered a technology difficult to implement (Parasuraman and Riley, 1997). However, in the 21st century and especially after 2010, AI technology has progressed significantly. Nowadays, the impact of AI technology and its applications pervade daily life and professional environments, encompassing speech and image recognition, autonomous driving, smart homes, among others. AI can autonomously deliver personalized services by analyzing historical human data (Lu et al., 2019). Particularly, the recent advancements in generative AI have provided a glimpse of the potential for achieving general AI. That said, understanding how current AI arrives at specific decisions or outcomes can be complex due to its reliance on vast amounts of data and intricate algorithms.

有趣的是,在最初的人机交互研究中,人工智能被认为是一种难以实施的技术(Parasuraman and Riley, 1997)。然而,在 21 世纪,尤其是 2010 年之后,人工智能技术取得了显著进展。如今,人工智能技术及其应用渗透到日常生活和专业环境中,包括语音和图像识别、自动驾驶、智能家居等。人工智能可以通过分析历史人类数据自主提供个性化服务(Lu et al., 2019)。特别是,最近在生成性人工智能方面的进展让人们看到了实现通用人工智能的潜力。也就是说,理解当前人工智能如何得出特定决策或结果可能是复杂的,因为它依赖于大量数据和复杂的算法。

3.5.2 From trust in automation to trust in AI

3.5.2 从对自动化的信任到对人工智能的信任

With the advancement and widespread applications of AI, trust in AI has indeed become a new focal point in the study of human-automation interaction. This transition redefines relationships between humans and automation, moving from reliance on technologies for repetitive, accuracy-driven tasks to expecting AI to demonstrate capabilities in learning, adapting, and collaborating (Kaplan et al., 2021). This evolution in trust requires AI systems to demonstrate not only technical proficiency but also adherence to ethical standards, legal compliance, and socially responsible behavior. As AI becomes more integrated into daily life and crucial decision making tasks, establishing trust in AI is essential. This necessitates a focus on enhancing transparency, explainability, fairness, and robustness within AI systems, which is also central to trustworthy AI.

随着人工智能的进步和广泛应用,对人工智能的信任确实成为人机交互研究的新焦点。这一转变重新定义了人类与自动化之间的关系,从依赖技术进行重复、以准确性为驱动的任务,转向期望人工智能展示学习、适应和协作的能力(Kaplan et al., 2021)。这种信任的演变要求人工智能系统不仅要展示技术熟练度,还要遵循伦理标准、法律合规和社会责任行为。随着人工智能越来越多地融入日常生活和关键决策任务,建立对人工智能的信任至关重要。这需要关注增强人工智能系统的透明度、可解释性、公平性和稳健性,这也是可信赖人工智能的核心。

While AI represents a new generation of automation technology with unique characteristics, research on trust in earlier forms of automation remains relevant. This historical perspective can inform the development of trust in AI by highlighting the important trust factors. Incorporating lessons from the past, the transition to AI additionally demands a renewed focus on ethical considerations, transparency, and user engagement to foster a deeper and more comprehensive trust.

虽然人工智能代表了一代具有独特特征的自动化技术,但对早期自动化形式的信任研究仍然具有相关性。这种历史视角可以通过强调重要的信任因素来为人工智能的信任发展提供指导。在借鉴过去经验的同时,向人工智能的过渡还需要重新关注伦理考虑、透明度和用户参与,以促进更深层次和更全面的信任。

3.5.3 A framework of trust in automation

3.5.3 自动化中的信任框架

Early theoretical models of trust in automation focused on attributes related to automation’s performance or competence, such as reliability, robustness, capability, and predictability (Sheridan, 1988; Malle and Ullman, 2021). In these models, trust was primarily grounded in the systems’ technical performance and their ability to meet user expectations reliably. Trust varied directly with the system’s demonstrated competence in executing tasks (Malle and Ullman, 2021). However, the progress of AI has broadened the scope of research on trust determinants to include considerations of automation’s inferred intentions and the ethical implications of its actions (Malle and Ullman, 2021).

早期的自动化信任理论模型主要关注与自动化性能或能力相关的属性,如可靠性、稳健性、能力和可预测性(Sheridan, 1988; Malle and Ullman, 2021)。在这些模型中,信任主要基于系统的技术性能及其可靠满足用户期望的能力。信任与系统在执行任务时展示的能力直接相关(Malle and Ullman, 2021)。然而,人工智能的发展扩大了对信任决定因素的研究范围,纳入了对自动化推断意图和其行为的伦理影响的考虑(Malle and Ullman, 2021)。

Individual differences are critical to human-automation trust. Some individuals apply frequently the machine heuristic, which is similar to trust propensity and represents the tendency to perceive automation as safer and more trustworthy than humans (Sundar and Kim, 2019). Moreover, an individual’s self-efficacy in using automation—the confidence in their ability to effectively utilize automation technologies—also plays a crucial role in shaping trust (Kraus et al., 2020); a higher sense of self-efficacy correlates with greater trust and willingness to use automated systems (Latikka et al., 2019). Furthermore, the degrees of familiarity and understanding of automated systems contribute to a more accurate evaluation of these systems’ competence, promoting a well-calibrated trust (Lee and See, 2004). Trust in automation, therefore, is a dynamic process, continuously recalibrated with the input of new information, knowledge, and experience (Muir, 1987).

个体差异对人机信任至关重要。一些个体经常应用机器启发式,这类似于信任倾向,代表了将自动化视为比人类更安全和更值得信赖的倾向(Sundar 和 Kim, 2019)。此外,个体在使用自动化方面的自我效能感——对有效利用自动化技术能力的信心——在塑造信任方面也起着至关重要的作用(Kraus 等, 2020);更高的自我效能感与更大的信任和使用自动化系统的意愿相关(Latikka 等, 2019)。此外,对自动化系统的熟悉程度和理解程度有助于更准确地评估这些系统的能力,从而促进良好校准的信任(Lee 和 See, 2004)。因此,对自动化的信任是一个动态过程,随着新信息、知识和经验的输入不断重新校准(Muir, 1987)。

Initial research on trust in automation adopted frameworks from interpersonal trust studies, positing a similar psychological structure in them (Muir, 1987). In practical research, factors affecting human-automation trust can also be categorized into trustor (human factors), trustee (automation factors), and the interaction context. This tripartite framework has been validated across various studies, affirming its applicability in understanding trust dynamics (Hancock et al., 2011; Hoff and Bashir, 2015; Drnec et al., 2016). Automation technology has evolved into the era of AI, inheriting characteristics of traditional automation while also exhibiting new features such as learning capabilities and adaptability. Factors influencing trust in AI based on this three-dimension framework are analyzed in detail in the next section from a sociocognitive perspective.

初步研究自动化中的信任采用了人际信任研究的框架,假设它们具有类似的心理结构(Muir, 1987)。在实际研究中,影响人机信任的因素也可以分为信任者(人类因素)、受托者(自动化因素)和互动背景。这一三方框架在各种研究中得到了验证,确认了其在理解信任动态中的适用性(Hancock et al., 2011; Hoff and Bashir, 2015; Drnec et al., 2016)。自动化技术已经发展到人工智能时代,继承了传统自动化的特征,同时也展现出学习能力和适应性等新特征。基于这一三维框架,影响对人工智能信任的因素将在下一节中从社会认知的角度进行详细分析。

4 A three-dimension framework of trust in AI

人工智能信任的三维框架

AI, nested within the broad category of automation technology, benefits from existing trust research in automation, despite its unique characteristics. The algorithmic black-box nature of AI poses challenges in understanding its operational mechanisms, and its ability for autonomous learning compounds the difficulty in predicting its behavior. According to theories of technology acceptance, trust plays a pivotal role in the development and adoption of AI (Siau and Wang, 2018). Moreover, it is crucial for both enduring human collaborations and effective cooperation with AI (Xie et al., 2019). Furthermore, AI’s limitations in understanding human intentions, preferences, and values present additional challenges (Dafoe et al., 2021). Thus, research on trust in AI can guide the development of trustworthy AI, promote its acceptance and human interaction, and reduce the risks of misuse and disuse.

人工智能作为自动化技术的一个广泛类别,尽管具有独特的特征,但仍受益于现有的自动化信任研究。人工智能的算法黑箱特性使得理解其操作机制面临挑战,而其自主学习的能力进一步增加了预测其行为的难度。根据技术接受理论,信任在人工智能的发展和采用中发挥着关键作用(Siau and Wang, 2018)。此外,信任对于持久的人类合作和与人工智能的有效合作至关重要(Xie et al., 2019)。此外,人工智能在理解人类意图、偏好和价值观方面的局限性带来了额外的挑战(Dafoe et al., 2021)。因此,关于人工智能信任的研究可以指导可信赖人工智能的发展,促进其接受和人机互动,并减少误用和不当使用的风险。

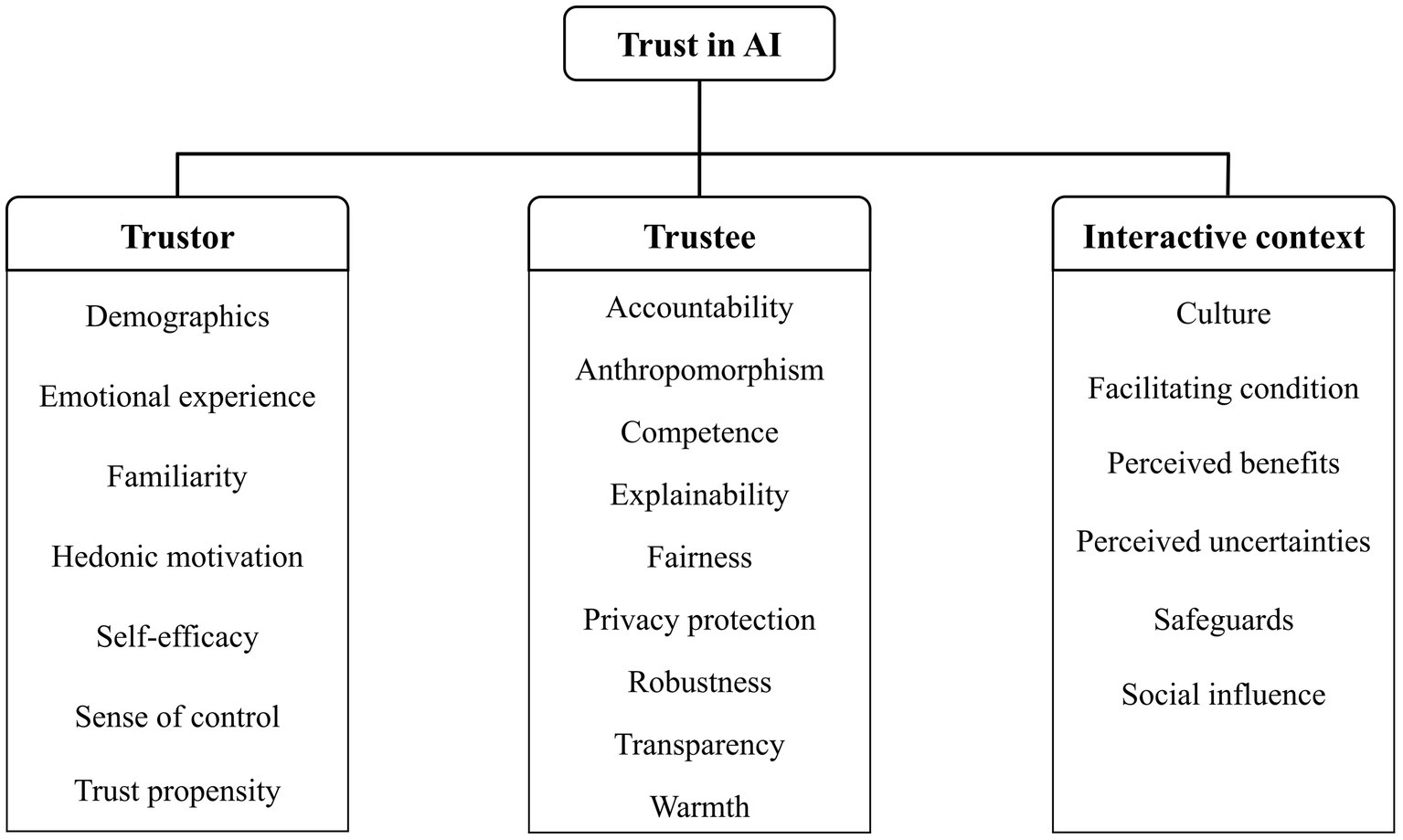

It is evident from our above review that trust, whether in interpersonal relationships or human-automation interactions, operates within a dyadic framework against an interactive context. Kaplan et al. (2021) also validated a similar framework through a meta-analysis of trust in AI, suggesting that the antecedents influencing trust in AI can be classified into three categories: human-related, AI-related, and context-related. In the following, we review factors influencing trust in AI related to these three dimensions, and Figure 1 shows what these factors are and to which dimension each of them belongs.

从我们上述的回顾中可以明显看出,无论是在个人关系还是人机交互中,信任都在一个双边框架内运作,并且处于一个互动的背景中。Kaplan et al. (2021) 通过对人工智能信任的元分析也验证了类似的框架,建议影响人工智能信任的前因可以分为三类:与人相关的、与人工智能相关的和与背景相关的。接下来,我们将回顾与这三个维度相关的影响人工智能信任的因素,图 1 显示了这些因素是什么以及它们各自属于哪个维度。

Figure 1. A three-dimension framework of trust that specifies the critical factors in each dimension that can affect trust in AI.

图 1。一个三维信任框架,指定了每个维度中可以影响对人工智能信任的关键因素。

4.1 Factors related to the trustor

4.1 与委托人相关的因素

4.1.1 Demographic variables

4.1.1 人口统计变量

The impacts of demographic variables on trust in AI are complicated. In a recent worldwide survey study conducted in 17 countries, Gillespie et al. (2023) found that gender differences in trust toward AI were generally minimal, with notable exceptions in a few countries (i.e., the United States, Singapore, Israel, and South Korea). Regarding age, while a trend of greater trust among the younger generation was prevalent, this pattern was reversed in China and South Korea, where the older population demonstrated higher levels of trust in AI. Additionally, the data indicated that individuals possessing university-level education or occupying managerial roles tended to exhibit higher trust in AI, pointing to the significant roles of educational background and professional status in shaping trust dynamics. The study further showed pronounced cross-country variations, identifying a tendency for placing more trust in AI in economically developing nations, notably China and India. Previous research has also found that culture and social groups can influence trust in AI (Kaplan et al., 2021; Lee and Rich, 2021). Therefore, the impact of demographic variables on trust in AI may be profoundly influenced by socio-cultural factors.

人口变量对人工智能信任的影响是复杂的。在最近的一项在 17 个国家进行的全球调查研究中,Gillespie et al. (2023)发现,性别差异对人工智能的信任通常较小,但在一些国家(即美国、新加坡、以色列和韩国)有显著例外。关于年龄,尽管年轻一代普遍表现出更高的信任趋势,但在中国和韩国,这一模式被逆转,老年人群体对人工智能表现出更高的信任水平。此外,数据表明,拥有大学学历或担任管理职位的个人往往对人工智能表现出更高的信任,这表明教育背景和职业地位在塑造信任动态中起着重要作用。研究进一步显示出明显的跨国差异,发现经济发展中国家(特别是中国和印度)对人工智能的信任倾向更高。以往的研究也发现,文化和社会群体可以影响对人工智能的信任(Kaplan et al., 2021; Lee and Rich, 2021)。 因此,人口变量对对人工智能信任的影响可能受到社会文化因素的深刻影响。

4.1.2 Familiarity and self-efficacy

4.1.2 熟悉度与自我效能感

An individual’s familiarity with AI, rooted in their knowledge and prior interactive experience, plays a pivotal role in trust formation (Gefen et al., 2003). Such familiarity not only reduces cognitive complexity by supplying essential background information and a cognitive framework, but also enables the formation of concrete expectations regarding the AI’s future behavior (Gefen, 2000). Additionally, a deeper understanding of AI can reduce the perceived risks and uncertainties associated with its use (Lu et al., 2019). Relatedly, AI use self-efficacy, or individuals’ confidence in their ability to effectively use AI, significantly influences acceptance and trust (REF). Familiarity and self-efficacy are both related to past interactive experience with AI, and both are positively correlated with a precise grasp of AI, thereby facilitating appropriate trust in AI.

个体对人工智能的熟悉程度,根植于他们的知识和先前的互动经验,在信任形成中发挥着关键作用(Gefen et al., 2003)。这种熟悉程度不仅通过提供必要的背景信息和认知框架来减少认知复杂性,还使得对人工智能未来行为的具体期望得以形成(Gefen, 2000)。此外,对人工智能的更深入理解可以减少与其使用相关的感知风险和不确定性(Lu et al., 2019)。相关地,人工智能使用的自我效能感,即个体对有效使用人工智能能力的信心,显著影响接受度和信任(REF)。熟悉程度和自我效能感都与过去与人工智能的互动经验相关,并且都与对人工智能的准确理解呈正相关,从而促进对人工智能的适当信任。

4.1.3 Hedonic motivation and emotional experience

4.1.3 享乐动机与情感体验

Hedonic motivation, an intrinsic form of motivation, can lead people to use AI in pursuit of enjoyment. Venkatesh et al. (2012) recognized this by incorporating hedonic motivation into the expanded Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model as a key determinant of technology acceptance. This form of motivation is instrumental in increasing user satisfaction and enjoyment derived from AI, thereby positively influencing their attitudes toward technology and enhancing their intention to use it (Gursoy et al., 2019).

享乐动机是一种内在的动机形式,可以促使人们使用人工智能以追求乐趣。Venkatesh et al. (2012) 通过将享乐动机纳入扩展的统一技术接受与使用理论(UTAUT)模型,认识到这一点,并将其作为技术接受的关键决定因素。这种动机形式在提高用户满意度和从人工智能中获得的乐趣方面起着重要作用,从而积极影响他们对技术的态度,并增强他们使用技术的意图(Gursoy et al., 2019)。

Emotional experience in the context of AI refers to the sense of security and comfort users feel when relying on AI, often described as emotional trust. It can reduce people’s perception of uncertainties and risks, and thus increase trust in AI. The acceptance and utilization of AI are guided by both cognitive judgments and affective responses. As such, it is crucial for trust research in AI to address both the cognitive and the emotional components (Gursoy et al., 2019). Specifically, emotional experience has been shown to directly impact the willingness to adopt AI-based recommendation systems, as seen in the context of travel planning (Shi et al., 2020).

在人工智能的背景下,情感体验指的是用户在依赖人工智能时所感受到的安全感和舒适感,通常被描述为情感信任。它可以减少人们对不确定性和风险的感知,从而增加对人工智能的信任。人工智能的接受和利用受到认知判断和情感反应的双重引导。因此,人工智能信任研究必须同时关注认知和情感成分(Gursoy et al., 2019)。具体而言,情感体验已被证明直接影响采用基于人工智能的推荐系统的意愿,这在旅行规划的背景中得到了体现(Shi et al., 2020)。

4.1.4 Sense of control 4.1.4 控制感

Sense of control represents individuals’ perception of their ability to monitor and influence AI decision-making processes. Dietvorst et al. (2018) found that algorithm aversion decreased when participants were allowed to adjust the outcomes of an imperfect algorithm, even if the adjustments were minimal. This finding underscores the importance of a sense of control in enhancing user satisfaction and trust in algorithms that are fundamental components of AI. Aoki (2021) found that AI-assisted nursing care plans that explicitly informed individuals that humans retained control over the decision-making processes significantly boosted trust in AI, compared to those who were not provided with this information. This highlights the importance of communicating human oversight in AI applications to enhance public trust. Similarly, Jutzi et al. (2020) found a favorable attitude toward AI in medical diagnosis when AI acted in a supportive capacity, reinforcing the value of positioning AI as an adjunct to human expertise.

控制感代表个体对其监控和影响人工智能决策过程能力的感知。Dietvorst et al. (2018) 发现,当参与者被允许调整不完美算法的结果时,即使调整很小,算法厌恶感也会减少。这个发现强调了控制感在增强用户满意度和对算法信任中的重要性,而算法是人工智能的基本组成部分。Aoki (2021) 发现,明确告知个体人类对决策过程保持控制的 AI 辅助护理计划显著提高了对人工智能的信任,相比之下,那些没有提供此信息的人信任度较低。这突显了在人工智能应用中传达人类监督的重要性,以增强公众信任。同样,Jutzi et al. (2020) 发现,当人工智能在支持性角色中发挥作用时,医疗诊断中对人工智能的态度较为积极,进一步强调了将人工智能定位为人类专业知识的辅助工具的价值。

4.1.5 Trust propensity 4.1.5 信任倾向

The propensity to trust refers to stable internal psychological factors affecting an individual’s inclination to trust, applicable to both people and technology. Research indicates that individuals with high trust propensity are more inclined to place trust in others, including strangers, and hold a general belief in the beneficial potential of technology (Brown et al., 2004). This tendency enables them to rely on technological systems without extensive evidence of their reliability. Attitudes toward new technologies vary significantly; some individuals readily adopt new technologies, while others exhibit skepticism or caution initially. This variation extends to AI, where trust propensity influences acceptance levels (Chi et al., 2021). Furthermore, trust propensity may intersect with personality traits. For instance, individuals experiencing loneliness may show lower trust in AI, whereas those with a penchant for innovation are more likely to trust AI (Kaplan et al., 2021).

信任倾向是指影响个体信任倾向的稳定内部心理因素,适用于人和技术。研究表明,具有高信任倾向的个体更倾向于信任他人,包括陌生人,并普遍相信技术的潜在益处(Brown et al., 2004)。这种倾向使他们能够在没有广泛可靠性证据的情况下依赖技术系统。对新技术的态度差异显著;一些个体乐于接受新技术,而另一些个体则最初表现出怀疑或谨慎。这种差异也延伸到人工智能,信任倾向影响接受程度(Chi et al., 2021)。此外,信任倾向可能与个性特征交叉。例如,感到孤独的个体可能对人工智能表现出较低的信任,而那些具有创新倾向的人更可能信任人工智能(Kaplan et al., 2021)。

4.2 Factors related to the trustee

4.2 与受托人相关的因素

4.2.1 Accountability 4.2.1 责任追究

Because of the complexity and potential wide-ranging impacts of AI, accountability is a key factor in establishing public trust in AI. Fears that AI cannot be held responsible hinder trust in AI. Therefore, people need assurance that clear processes exist to handle AI issues and that specific parties, like developers, providers, or regulators, are accountable.

由于人工智能的复杂性和潜在的广泛影响,问责制是建立公众对人工智能信任的关键因素。人们担心人工智能无法被追责,这阻碍了对人工智能的信任。因此,人们需要确保存在明确的流程来处理人工智能问题,并且特定的相关方,如开发者、提供者或监管者,需承担责任。

When people think that AI cannot be held accountable, they are less willing to let AI make decisions and tend to blame it less. Research has found that in the service industry when service providers make mistakes that result in customer losses, participants believe that the robot responsible for the mistake bears less responsibility compared to a human service provider, and the service-providing company should bear more responsibility (Leo and Huh, 2020). This occurs probably because people perceive that robots have poorer controllability over tasks. People are reluctant to allow AI to make moral decisions because AI is perceived to lack mind perception (Bigman and Gray, 2018). Bigman et al. (2023) found that algorithmic discrimination elicits less anger, with people showing less moral outrage toward algorithmic (as opposed to human) discrimination and being less inclined to blame the organization, but it does lower the evaluation of the company. This might be because people perceive algorithms as lacking prejudicial motivation.

当人们认为人工智能无法承担责任时,他们更不愿意让人工智能做出决策,并且倾向于较少指责它。研究发现,在服务行业中,当服务提供者犯错导致客户损失时,参与者认为负责错误的机器人相比于人类服务提供者承担的责任较少,而提供服务的公司应该承担更多责任(Leo 和 Huh, 2020)。这可能是因为人们认为机器人对任务的可控性较差。人们不愿意让人工智能做出道德决策,因为人工智能被认为缺乏心智感知(Bigman 和 Gray, 2018)。Bigman 等人 (2023) 发现,算法歧视引发的愤怒较少,人们对算法(而非人类)歧视表现出较少的道德愤慨,并且不太倾向于指责组织,但这确实降低了对公司的评价。这可能是因为人们认为算法缺乏偏见动机。

4.2.2 Anthropomorphism 4.2.2 拟人化

Anthropomorphism, the tendency to ascribe human-like qualities to non-human entities such as computers and robots, significantly affects individuals’ trust in these technologies (Bartneck et al., 2009). Cominelli et al. (2021) found that robots perceived as highly human-like are more likely to be trusted by individuals. Beyond physical appearance and vocal cues, emotional expression is a crucial aspect of anthropomorphism. Troshani et al. (2021) found that robots exhibiting positive emotions are more likely to receive increased trust and investment from people. Similarly, Li and Sung (2021) demonstrated through a network questionnaire that anthropomorphized AI correlates with more positive attitudes toward the technology. Experimental studies have corroborated these findings, suggesting that psychological distance plays a mediating role in how anthropomorphism influences perceptions of AI (Li and Sung, 2021).

拟人化,即将人类特质赋予计算机和机器人等非人类实体的倾向,显著影响个体对这些技术的信任(Bartneck et al., 2009)。Cominelli et al. (2021)发现,被认为高度拟人化的机器人更容易获得个体的信任。除了外观和声音线索,情感表达是拟人化的一个关键方面。Troshani et al. (2021)发现,表现出积极情感的机器人更有可能获得人们的信任和投资。同样,Li and Sung (2021)通过网络问卷调查证明,拟人化的人工智能与对该技术更积极的态度相关。实验研究证实了这些发现,表明心理距离在拟人化如何影响对人工智能的感知中起到中介作用(Li and Sung, 2021)。

4.2.3 Competence and warmth

4.2.3 能力与温暖

The key to evaluating trustworthy AI is whether AI does what it claims to do (Schwartz et al., 2022). The claims of AI can be analyzed from two perspectives: one is whether it fulfills the functional requirements of its users, and the other is whether it demonstrates good intentions toward its users. This directly corresponds to the perceptions of competence and warmth of AI.

评估可信赖人工智能的关键在于人工智能是否能够实现其所声称的功能(Schwartz et al., 2022)。人工智能的声明可以从两个角度进行分析:一个是它是否满足用户的功能需求,另一个是它是否对用户表现出良好的意图。这直接对应于人们对人工智能的能力和温暖的感知。

In both interpersonal trust and human-automation trust, competence and warmth are pivotal in shaping perceptions of trustworthiness (Kulms and Kopp, 2018). The stereotype content model (SCM) posits that stereotypes and interpersonal perceptions of a group are formed along two dimensions: warmth and competence (Fiske et al., 2002). Warmth reflects how one perceives the intentions (positive or negative) of others, while competence assesses the perceived ability of others to fulfill those intentions.

在人际信任和人机信任中,能力和温暖在塑造信任感知方面至关重要(Kulms 和 Kopp, 2018)。刻板印象内容模型(SCM)认为,群体的刻板印象和人际感知是沿着两个维度形成的:温暖和能力(Fiske 等, 2002)。温暖反映了一个人对他人意图(积极或消极)的感知,而能力则评估他人实现这些意图的能力。

Trust and stereotype share a foundational link through the attitudes and beliefs individuals hold toward others (Kong, 2018). Moreover, in Mayer et al.’s (1995) trust model, the trustworthiness dimensions of ability and benevolence align closely with the competence and warmth dimensions in the SCM, respectively. Therefore, warmth and competence may be two core components of trustworthiness affecting interpersonal trust. The significance of these two dimensions is evident in their substantial influence on individuals’ evaluations and behaviors toward others (Mayer et al., 1995; Fiske, 2012).

信任和刻板印象通过个体对他人的态度和信念共享一个基础联系(Kong, 2018)。此外,在Mayer 等人(1995)的信任模型中,能力和善意的信任维度与 SCM 中的能力和温暖维度紧密对齐。因此,温暖和能力可能是影响人际信任的信任 worthiness 的两个核心组成部分。这两个维度的重要性在于它们对个体对他人的评估和行为的显著影响(Mayer 等人,1995;Fiske, 2012)。

Competence is the key factor influencing trust in automation (Drnec et al., 2016). When users observe errors in the automated system, their trust in it decreases, leading them to monitor the system more closely (Muir and Moray, 1996). However, an AI agent that is competent but not warm might not be trusted, because, in certain situations, intention is a crucial influencing factor of trust (Gilad et al., 2021). For instance, although users may recognize the technical proficiency of autonomous vehicles (AVs) in navigating complex environments, concerns that AVs may compromise safety for speed or prioritize self-preservation in emergencies can undermine trust (Xie et al., 2019). Thus, AI needs to demonstrate good intentions to build trust. This is exemplified by AI’s social intelligence, such as understanding and responding to user emotions, which significantly bolsters trust in conversational agents (Rheu et al., 2021). Moreover, trust in AI is generally lower in domains traditionally dominated by human expertise, potentially due to concerns about the intentions of AI (Lee, 2018).

能力是影响对自动化信任的关键因素 (Drnec et al., 2016)。当用户观察到自动化系统中的错误时,他们对系统的信任会下降,从而使他们更加密切地监控该系统 (Muir and Moray, 1996)。然而,一个能力强但缺乏温暖的人工智能代理可能不会被信任,因为在某些情况下,意图是信任的重要影响因素 (Gilad et al., 2021)。例如,尽管用户可能会认可自动驾驶汽车(AVs)在复杂环境中导航的技术能力,但对自动驾驶汽车可能为了速度而妥协安全或在紧急情况下优先考虑自我保护的担忧可能会削弱信任 (Xie et al., 2019)。因此,人工智能需要展示良好的意图以建立信任。这可以通过人工智能的社交智能来体现,例如理解和回应用户情感,这显著增强了对对话代理的信任 (Rheu et al., 2021)。此外,在传统上由人类专业知识主导的领域,对人工智能的信任通常较低,这可能是由于对人工智能意图的担忧 (Lee, 2018)。

4.2.4 Privacy protection 4.2.4 隐私保护

The rapid development of AI, facilitated greatly by network technology, raises privacy concerns, especially when third parties access data through networks without user consent, risking privacy misuse (Featherman and Pavlou, 2003). Additionally, while AI’s ability to tailor services to individual needs can enhance user satisfaction, this often requires accessing personal information, thus creating a dilemma between personalization benefits and privacy risks (Guo et al., 2016). Network technologies have amplified privacy risks, resulting in individuals losing control over the flow of their private data. As a result, privacy concerns play a crucial role in establishing online trust, and internet users are highly concerned about websites’ privacy policies, actively seeking clues to ensure the protection of their personal information (Ang et al., 2001). Research has found that providing adequate privacy protection measures directly influences people’s trust in AI and their willingness to use it (Vimalkumar et al., 2021; Liu and Tao, 2022).

人工智能的快速发展在网络技术的推动下引发了隐私担忧,尤其是当第三方在没有用户同意的情况下通过网络访问数据时,存在隐私被滥用的风险(Featherman and Pavlou, 2003)。此外,虽然人工智能能够根据个人需求定制服务,从而提高用户满意度,但这通常需要访问个人信息,因此在个性化利益和隐私风险之间形成了两难局面(Guo et al., 2016)。网络技术加剧了隐私风险,导致个人失去对私人数据流动的控制。因此,隐私问题在建立在线信任中起着至关重要的作用,互联网用户对网站的隐私政策高度关注,积极寻求线索以确保个人信息的保护(Ang et al., 2001)。研究发现,提供足够的隐私保护措施直接影响人们对人工智能的信任以及他们使用人工智能的意愿(Vimalkumar et al., 2021; Liu and Tao, 2022)。

4.2.5 Robustness and fairness

4.2.5 鲁棒性和公平性

Sheridan (1988) argued that robustness should be an important determinant of trust. The robustness of AI refers to the reliability and consistency of its operations and results, including its performance under diverse and unexpected conditions (High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG), 2019). The fairness of AI involves treating all users equitably, making unbiased decisions, and not discriminating against any group (Shin and Park, 2019). Robustness is a key factor influencing trust in AI. Rempel et al. (1985) identified three components of trust from a dynamic perspective, including predictability (the consistency of actions over time), dependability (reliability based on past experience), and faith (belief in future behavior). Based on the definitions, these components also correspond to the formation of the perception of robustness. Compared to trust in humans, building trust in AI takes more time; moreover, when AI encounters problems, the loss of trust in it happens more rapidly (Dzindolet et al., 2003). Furthermore, the simpler the task in which the error occurs, the greater the loss of trust (Madhavan et al., 2006).

谢里丹 (1988) 认为,稳健性应该是信任的重要决定因素。人工智能的稳健性指的是其操作和结果的可靠性和一致性,包括在多样和意外条件下的表现 (人工智能高级专家组 (AI HLEG), 2019)。人工智能的公平性涉及公平对待所有用户,做出无偏见的决策,并且不歧视任何群体 (申和朴, 2019)。稳健性是影响对人工智能信任的关键因素。伦佩尔等 (1985) 从动态角度识别了信任的三个组成部分,包括可预测性(行动的一致性)、可靠性(基于过去经验的可靠性)和信念(对未来行为的信任)。根据这些定义,这些组成部分也对应于稳健性感知的形成。与对人类的信任相比,建立对人工智能的信任需要更多时间;此外,当人工智能遇到问题时,对其信任的丧失发生得更快 (津多莱特等, 2003)。 此外,错误发生的任务越简单,信任的损失就越大(Madhavan et al., 2006)。

Because robustness and fairness are vulnerable to data bias, from both theoretical and practical standpoints, these two factors are closely related. Robustness serves as a crucial foundation for fairness, with the presence of discrimination and bias often signaling a lack of robustness. For example, the training data used for developing large language models often contain biases, and research has found that ChatGPT replicates gender biases in reference letters written for hypothetical employees (Wan et al., 2023). Such disparities underscore the importance of aligning AI with human values, as perceived fairness significantly influences users’ trust in AI technologies (Angerschmid et al., 2022).

由于鲁棒性和公平性容易受到数据偏见的影响,从理论和实践的角度来看,这两个因素密切相关。鲁棒性是公平性的关键基础,歧视和偏见的存在往往表明鲁棒性不足。例如,用于开发大型语言模型的训练数据通常包含偏见,研究发现 ChatGPT 在为假设员工撰写的推荐信中复制了性别偏见(Wan et al., 2023)。这种差异突显了将人工智能与人类价值观对齐的重要性,因为感知的公平性显著影响用户对人工智能技术的信任(Angerschmid et al., 2022)。

4.2.6 Transparency and explainability

4.2.6 透明度和可解释性

Users need to understand how and why AI makes specific decisions, which corresponds, respectively, to transparency and explainability, before trusting in it. However, this is not an easy task for AI practitioners and stakeholders. Because of the mechanisms of algorithms, particularly the opacity of neural networks, it is difficult for humans to fully comprehend their decision-making process (Shin and Park, 2019).

用户需要理解人工智能如何以及为什么做出特定决策,这分别对应于透明度和可解释性,才能信任它。然而,这对人工智能从业者和利益相关者来说并不是一项简单的任务。由于算法的机制,特别是神经网络的复杂性,人类很难完全理解它们的决策过程(Shin and Park, 2019)。

Transparent AI models with clear explanations of their decision-making processes help users gain confidence in the system’s capabilities and accuracy. Moreover, transparency in AI design and implementation helps identify potential sources of bias, allowing developers to address these issues and ensure the AI system treats all users fairly. The concepts of transparency and explainability are deeply interconnected; explainability, in particular, plays a crucial role in reducing users’ perceived risks associated with AI systems (Qin et al., 2020). Additionally, providing reasonable explanations after AI errors can restore people’s trust in AI (Angerschmid et al., 2022).

透明的人工智能模型及其决策过程的清晰解释帮助用户增强对系统能力和准确性的信心。此外,人工智能设计和实施中的透明度有助于识别潜在的偏见来源,使开发者能够解决这些问题,确保人工智能系统公平对待所有用户。透明性和可解释性的概念密切相关;尤其是可解释性在降低用户对人工智能系统的感知风险方面发挥着关键作用(Qin et al., 2020)。此外,在人工智能出现错误后提供合理的解释可以恢复人们对人工智能的信任(Angerschmid et al., 2022)。

That said, the impact of transparency and explainability on trust in AI shows mixed results. Leichtmann et al. (2022) found that displaying AI’s decision-making process through graphical and textual information enhances users’ trust in the AI program. However, Wright et al. (2020) found no significant difference in trust levels attributed to varying degrees of transparency in simulated military tasks for target detection. Furthermore, in a task of using AI assistance to rate movies, Schmidt et al. (2020) observed that increased transparency in AI-assisted movie rating tasks paradoxically reduced user trust.

尽管如此,透明度和可解释性对人工智能信任的影响结果不一。Leichtmann et al. (2022)发现,通过图形和文本信息展示人工智能的决策过程可以增强用户对人工智能程序的信任。然而,Wright et al. (2020)发现,在模拟军事任务中,针对目标检测的不同透明度并未显著影响信任水平。此外,在使用人工智能辅助评分电影的任务中,Schmidt et al. (2020)观察到,人工智能辅助电影评分任务中透明度的增加反而降低了用户的信任。

Therefore, the relationship between transparency and trust in AI is intricate. Appropriate levels of transparency and explainability can enhance people’s trust in AI, but excessive information might be confusing (Kizilcec, 2016), thereby reducing their trust in AI. The absence of clear operational definitions for AI’s transparency and explainability complicates the determination of the optimal transparency levels that effectively build trustworthy AI. In general, lack of transparency indeed hurts trust in AI, but high levels of transparency do not necessarily lead to good results.

因此,透明度与对人工智能信任之间的关系是复杂的。适当的透明度和可解释性可以增强人们对人工智能的信任,但过多的信息可能会造成困惑(Kizilcec, 2016),从而降低他们对人工智能的信任。缺乏对人工智能透明度和可解释性的明确操作定义,使得确定有效建立可信赖人工智能的最佳透明度水平变得复杂。一般来说,缺乏透明度确实会损害对人工智能的信任,但高水平的透明度并不一定会带来良好的结果。

4.3 Factors related to the interactive context of trust

4.3 与信任互动背景相关的因素

4.3.1 Perceived uncertainties and benefits

4.3.1 感知的不确定性和利益

AI is surrounded by various unknowns, including ethical and legal uncertainties, that are critical evaluations of the interactive environment. Lockey et al. (2020) emphasized uncertainties as a key factor influencing trust in AI. Similarly, Jing et al. (2020) conducted a literature review and discovered a negative correlation between perceived uncertainties and risks with the acceptance of autonomous driving. Furthermore, perceived uncertainties in the application of AI vary across different applications, particularly pronounced in medical expert systems and vehicles (Yang and Wibowo, 2022).

AI 周围存在各种未知因素,包括伦理和法律的不确定性,这些都是对互动环境的关键评估。Lockey et al. (2020) 强调不确定性是影响对 AI 信任的关键因素。同样,Jing et al. (2020) 进行了一项文献综述,发现感知的不确定性与风险与对自动驾驶的接受之间存在负相关。此外,AI 应用中的感知不确定性在不同应用中有所不同,尤其在医疗专家系统和车辆中表现得尤为明显 (Yang and Wibowo, 2022)。

Perceived benefits, such as time savings, cost reductions, and increased convenience, highlight the recognized advantages of using AI (Kim et al., 2008). Liu and Tao (2022) found that perceived benefits, such as usefulness, could facilitate the use of smart healthcare services. Although perceived benefits can be viewed as characteristics of AI the trustee, they can also be highly socially dependent, mainly because the impacts of these benefits are not uniform across all users: For instance, while AI applications may enhance work efficiency for some, they could pose a risk of unemployment for others (Pereira et al., 2023). Therefore, perceived benefits are intricately linked to the social division of labor, underscoring their importance within the broader interactive context of AI usage.

感知的好处,如节省时间、降低成本和增加便利性,突显了使用人工智能的公认优势(Kim et al., 2008)。Liu and Tao (2022)发现,感知的好处,如有用性,可以促进智能医疗服务的使用。尽管感知的好处可以被视为人工智能受托人的特征,但它们也可能高度依赖于社会,主要是因为这些好处的影响在所有用户中并不均匀:例如,虽然人工智能应用可能提高某些人的工作效率,但对其他人来说可能会带来失业风险(Pereira et al., 2023)。因此,感知的好处与社会分工密切相关,强调了它们在人工智能使用的更广泛互动背景中的重要性。

4.3.2 Safeguards 4.3.2 保障措施

Drawing from the concept of institution-based trust, safeguards are understood as the belief in existing institutional conditions that promote responsible and ethical AI usage (McKnight et al., 1998). Because AI is perceived as lacking agency and cannot be held accountable for its actions (Bigman and Gray, 2018), safeguards play a crucial role in ensuring human trust in AI.

基于制度信任的概念,保障被理解为对促进负责任和伦理的人工智能使用的现有制度条件的信任(McKnight et al., 1998)。由于人工智能被认为缺乏自主性,无法对其行为负责(Bigman and Gray, 2018),保障在确保人类对人工智能的信任中发挥着至关重要的作用。

Lockey et al. (2020), however, found that a mere 19–21% of Australians considered the current safety measures adequate for AI’s safe application, underscoring a significant trust gap. Their analysis further showed that perception of these safeguards was a strong predictor of trust in AI. In today’s AI landscape, establishing legal frameworks to protect human rights and interests is crucial for fostering trust. A prime example is the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Enacted in 2018, GDPR introduces stringent privacy protections and sets clear standards for algorithmic transparency and accountability (Felzmann et al., 2019).

Lockey 等人 (2020) 发现,仅有 19%–21% 的澳大利亚人认为当前的安全措施足以确保人工智能的安全应用,这突显了信任的重大缺口。他们的分析进一步表明,这些安全措施的认知是信任人工智能的强有力预测因素。在当今的人工智能环境中,建立法律框架以保护人权和利益对于促进信任至关重要。一个典型的例子是欧盟的通用数据保护条例 (GDPR)。GDPR 于 2018 年实施,引入了严格的隐私保护,并为算法透明度和问责制设定了明确的标准 (Felzmann 等人, 2019)。

4.3.3 Social influence and facilitating condition

4.3.3 社会影响与促进条件

Social influence is defined by the extent to which an individual perceives endorsement of specific behaviors by their social network, including encouragement from influential members to adopt new technologies (Gursoy et al., 2019). It is a crucial construct in the UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Social influence theory posits that individuals tend to conform to the norms and beliefs of their social network (Shi et al., 2020). When individuals perceive that the use of AI is socially acceptable, they are more likely to experience positive emotions toward it, leading to an increase in their emotional trust in AI.

社会影响被定义为个体感知其社交网络对特定行为的支持程度,包括来自有影响力成员的鼓励,以采用新技术(Gursoy et al., 2019)。这是 UTAUT 中的一个关键构念(Venkatesh et al., 2003)。社会影响理论认为,个体倾向于遵循其社交网络的规范和信念(Shi et al., 2020)。当个体感知到使用人工智能是社会可接受的,他们更可能对其产生积极情绪,从而增加对人工智能的情感信任。

Facilitating condition is another critical variable in the UTAUT model, referring to the extent to which individuals perceive organizational, group, or infrastructural support in using AI (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Chi et al. (2021) found that facilitating robot-use conditions could improve users’ trust in social robots in service scenarios.

促进条件是 UTAUT 模型中的另一个关键变量,指的是个人在使用人工智能时感知到的组织、群体或基础设施支持的程度 (Venkatesh et al., 2003)。Chi et al. (2021)发现,促进机器人使用的条件可以提高用户在服务场景中对社交机器人的信任。

4.3.4 Culture 4.3.4 文化

Cultural factors can significantly influence trust and acceptance of AI. For instance, cultures with high uncertainty avoidance are more inclined to trust and depend on AI (Kaplan et al., 2021), and the level of trust in AI also varies between individualistic and collectivistic cultures (Chi et al., 2023). Moreover, cultural influences may interact with economic factors to affect AI trust. Gillespie et al. (2023) found that individuals in the emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, China, and South Africa, exhibit higher levels of trust, in comparison to developed nations, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, and France. Furthermore, the impact of culture on AI trust can be mediated through social influence, highlighting the importance of social norms (Chi et al., 2023).

文化因素可以显著影响对人工智能的信任和接受度。例如,高不确定性规避的文化更倾向于信任和依赖人工智能(Kaplan et al., 2021),而对人工智能的信任水平在个人主义和集体主义文化之间也有所不同(Chi et al., 2023)。此外,文化影响可能与经济因素相互作用,从而影响对人工智能的信任。Gillespie et al. (2023)发现,像巴西、印度、中国和南非等新兴经济体的个体表现出比英国、澳大利亚、日本和法国等发达国家更高的信任水平。此外,文化对人工智能信任的影响可以通过社会影响进行中介,突显了社会规范的重要性(Chi et al., 2023)。

5 Implications for enhancing trustworthy AI

增强可信赖人工智能的五个启示

While intention is pivotal in interpersonal trust, competence is paramount in human-automation trust. Nonetheless, research on trust in AI encompasses both competence and intention, indicating that AI is perceived through a combination of human-like and automated characteristics, reflecting a sociocognitive perspective on trust in AI (Kulms and Kopp, 2018). Understanding how trust in AI forms from this perspective and integrating the resulting knowledge into the design and applications of AI systems will be critical to foster their effective use and the collaboration between humans and AI.

虽然意图在人际信任中至关重要,但能力在人机信任中更为重要。然而,关于人工智能信任的研究涵盖了能力和意图,表明人工智能是通过人类特征和自动化特征的结合来感知的,反映了对人工智能信任的社会认知视角(Kulms and Kopp, 2018)。理解从这一视角形成的人工智能信任,并将所获得的知识整合到人工智能系统的设计和应用中,将对促进其有效使用以及人类与人工智能之间的合作至关重要。

The proposed three-dimension framework of trust in AI not only encompasses the desired characteristics of AI but also emphasizes enhancing AI literacy among users and refining the interactive context. The framework highlights users’ expectations of AI and can help developers and managers grasp user concerns and needs. In addition, given the imperative to reduce perceived uncertainties associated with AI, it becomes critical to address concerns related to privacy protection in AI applications, ensure accountability, and meet the demand for enhanced safeguard measures.

所提出的三维信任框架不仅涵盖了对人工智能的期望特征,还强调了提高用户的人工智能素养和完善互动环境。该框架突出了用户对人工智能的期望,可以帮助开发者和管理者理解用户的关注和需求。此外,鉴于减少与人工智能相关的感知不确定性的必要性,解决与人工智能应用中的隐私保护相关的担忧、确保问责制以及满足对增强保护措施的需求变得至关重要。

The three-dimension framework also provides a solid foundation for developing ethical standards and policies that can enhance trustworthy AI. In social psychology, competence and warmth are critical for assessing trustworthiness. These dimensions are equally vital in evaluating AI. Specifically, robustness and safety illustrate competence, whereas fairness and privacy protection embody warmth. Thus, in formulating ethical standards for trustworthy AI, we would recommend focusing on the key dimensions of competence and warmth. For example, in developing and deploying AI applications, it is critical to conduct an ethical evaluation based on their competence and warmth. This evaluation ensures that the applications are functionally effective and possess benevolent intentions toward humanity. In addition, as AI technology advances, its potential to infringe upon human rights intensifies, underscoring the increasing importance of evaluating its warmth.

三维框架还为制定能够增强可信赖人工智能的伦理标准和政策提供了坚实的基础。在社会心理学中,能力和温暖是评估可信赖性的关键。这些维度在评估人工智能时同样至关重要。具体而言,稳健性和安全性体现了能力,而公平性和隐私保护则体现了温暖。因此,在制定可信赖人工智能的伦理标准时,我们建议关注能力和温暖这两个关键维度。例如,在开发和部署人工智能应用时,基于其能力和温暖进行伦理评估至关重要。这一评估确保应用在功能上有效,并对人类怀有善意。此外,随着人工智能技术的进步,其侵犯人权的潜力加剧,进一步凸显了评估其温暖的重要性。

Recognizing how individual characteristics influence trust in AI can guide the development of personalized and adaptive AI interaction strategies. These strategies, tailored to meet the specific needs and preferences of diverse users, can foster a sustained and appropriate trust in AI. While some individuals may place excessive trust in AI because of a high trust propensity, others, hindered by limited understanding of AI and a lower sense of self-efficacy, may demonstrate a lack of trust. Lockey et al. (2020) discovered a widespread desire among individuals to learn more about AI. Therefore, in developing trustworthy AI, it is crucial to acknowledge the varying levels of trust people have toward AI and to devise effective communication strategies, engaging in AI education to bridge this knowledge gap.

认识到个体特征如何影响对人工智能的信任,可以指导个性化和自适应人工智能互动策略的发展。这些策略旨在满足不同用户的特定需求和偏好,可以促进对人工智能的持续和适当的信任。虽然一些个体可能因为高信任倾向而对人工智能过度信任,但另一些人由于对人工智能的理解有限和自我效能感较低,可能表现出缺乏信任。Lockey et al. (2020) 发现个体普遍渴望了解更多关于人工智能的信息。因此,在开发可信的人工智能时,承认人们对人工智能的信任程度差异至关重要,并制定有效的沟通策略,参与人工智能教育以弥补这一知识差距。

Moreover, hedonic motivation plays a critical role in shaping trust in AI, with the potential to cause users to overtrust AI systems. For example, algorithms behind short video apps often leverage this motivation, leading to excessive requests for user data (Trifiro, 2023). Despite users’ general inclination to protect their privacy, they often adopt a pragmatic approach toward privacy protection, a discrepancy referred to as the privacy paradox (Sundar and Kim, 2019). Therefore, it is essential to be vigilant against the overtrust in AI that may result from an excessive pursuit of enjoyment and entertainment.

此外,享乐动机在塑造对人工智能的信任方面发挥着关键作用,可能导致用户对人工智能系统的过度信任。例如,短视频应用背后的算法通常利用这种动机,导致对用户数据的过度请求(Trifiro, 2023)。尽管用户通常倾向于保护他们的隐私,但他们往往采取务实的隐私保护方法,这种差异被称为隐私悖论(Sundar and Kim, 2019)。因此,必须警惕因过度追求享乐和娱乐而可能导致的对人工智能的过度信任。

Furthermore, power asymmetry often results in trust asymmetry. The prevailing trust in AI serves as a pertinent example of this asymmetry, where interactions with AI-driven technologies may engender a perceived sense of power or dominance among users. Such perceptions significantly influence the dynamics of trust in AI (Fast and Schroeder, 2020). Consequently, the influence of this sense of power on human interactions with AI necessitates further investigation.

此外,权力不对称往往导致信任不对称。对人工智能的普遍信任就是这种不对称的一个相关例子,在与人工智能驱动的技术互动时,用户可能会产生一种权力或主导感。这种感知显著影响了人们对人工智能的信任动态(Fast and Schroeder, 2020)。因此,这种权力感对人类与人工智能互动的影响需要进一步研究。

Gaining insight into the factors affecting AI’s trustworthiness enables a more sophisticated approach to identifying and managing the inherent risks associated with its application. Notably, anthropomorphism, the attribution of human-like qualities to AI, significantly influences users’ emotional trust, potentially enhancing AI’s acceptance and trustworthiness (Glikson and Woolley, 2020). Anthropomorphized AI might be more readily accepted and trusted by users, yet this could also mask its inherent limitations and potential risks. Further, attributing human traits to AI can lead to unrealistic expectations about its capabilities, including agency and moral judgment, thereby fostering misconceptions about its competence. Thus, cultivating trustworthy AI requires ensuring that users possess an accurate understanding of AI’s anthropomorphic features.

深入了解影响人工智能可信度的因素,使我们能够更复杂地识别和管理与其应用相关的固有风险。值得注意的是,人性化,即将类人特质归于人工智能,显著影响用户的情感信任,可能增强人工智能的接受度和可信度(Glikson and Woolley, 2020)。人性化的人工智能可能更容易被用户接受和信任,但这也可能掩盖其固有的局限性和潜在风险。此外,将人类特征归于人工智能可能导致对其能力的非现实期望,包括代理性和道德判断,从而助长对其能力的误解。因此,培养可信的人工智能需要确保用户对人工智能的人性化特征有准确的理解。

Policymakers focused on trustworthy AI must recognize the significant influence of social, organizational, and institutional factors in shaping AI perceptions within the interactive context of trust. The mass media plays a pivotal role in influencing public attitudes toward AI, either by highlighting uncertainties or by raising awareness of new technological advancements. A series of studies have shown the significant role of media in promoting emerging technologies (Du et al., 2021). Media headlines can influence people’s emotional responses, thereby affecting their willingness to adopt technology (Anania et al., 2018). Mass media can also influence trust in AI by impacting social influence and self-efficacy. Given these dynamics, regulating mass media to ensure accurate representation of AI is crucial. Policymakers should additionally prioritize the establishment of clear laws and regulations, define responsibilities for AI failures, and engage in transparent communication with the public to mitigate perceived uncertainties.

政策制定者关注可信赖的人工智能,必须认识到社会、组织和制度因素在信任的互动背景中塑造人工智能认知的重要影响。大众媒体在影响公众对人工智能的态度方面发挥着关键作用,既可以通过突出不确定性来影响公众,也可以通过提高对新技术进步的认识来实现。一系列研究表明,媒体在促进新兴技术方面发挥了重要作用(Du et al., 2021)。媒体标题可以影响人们的情感反应,从而影响他们采用技术的意愿(Anania et al., 2018)。大众媒体还可以通过影响社会影响力和自我效能感来影响对人工智能的信任。鉴于这些动态,规范大众媒体以确保对人工智能的准确表述至关重要。政策制定者还应优先建立明确的法律法规,定义人工智能失败的责任,并与公众进行透明沟通,以减轻感知的不确定性。

For example, trust in autonomous vehicles is dynamic (Luo et al., 2020) and easily swayed by mass media (Lee et al., 2022). Furthermore, media portrayals often lack objectivity, with companies overstating autonomy levels in promotions, whereas media primarily reports on accidents. Therefore, ensuring balanced and factual media representations is essential to foster an environment where people can develop informed trust in autonomous vehicles. Moreover, implementing sensible legislation and regulations, as well as clarifying responsibility in accidents involving autonomous vehicles, is vital for public endorsement.

例如,对自动驾驶汽车的信任是动态的(Luo et al., 2020),并且容易受到大众媒体的影响(Lee et al., 2022)。此外,媒体的描绘往往缺乏客观性,企业在宣传中夸大了自主性水平,而媒体主要报道事故。因此,确保媒体的平衡和事实的表现对于培养人们对自动驾驶汽车的知情信任至关重要。此外,实施合理的立法和法规,以及明确在涉及自动驾驶汽车的事故中的责任,对于公众的支持至关重要。

High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG) (2019) delineated seven crucial requirements for trustworthy AI: human agency and oversight, technical robustness and safety, privacy and data governance, transparency, diversity, non-discrimination and fairness, societal and environmental wellbeing, and accountability. The factors influencing trust in AI as we have reviewed (see Figure 1) are generally consistent with these requirements. High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG) (2019) also proposes communication, education, and training as key non-technical strategies for promoting trustworthy AI, again consistent with our recommendations derived from the literature.

人工智能高级专家组 (AI HLEG) (2019) 划定了七个可信赖人工智能的关键要求:人类代理和监督、技术稳健性和安全性、隐私和数据治理、透明度、多样性、非歧视和公平、社会和环境福祉,以及问责制。我们回顾的影响人工智能信任的因素(见 图 1)通常与这些要求一致。人工智能高级专家组 (AI HLEG) (2019) 还提出沟通、教育和培训作为促进可信赖人工智能的关键非技术策略,这与我们从文献中得出的建议一致。

Generative AI has emerged as the most noteworthy development in AI technologies in recent years, with products such as GPT and Sora showing impressive capabilities in content generation and analysis (Yang et al., 2024). For instance, videos created by Sora can be indistinguishably realistic. Even large language models are being utilized to explain other AI models, enhancing AI’s explainability (Bills et al., 2023). As AI’s capabilities grow, so does its impact on society, including potential negative effects, such as the ease of generating fraudulent content through generative AI. Concurrently, governments worldwide are introducing laws and regulations to guide AI development responsibly. On March 13, 2024, the European Union passed The AI Act, the world’s first comprehensive regulatory framework for AI (European Parliament, 2024). It categorizes AI usage by risk levels, banning its use in certain areas such as social scoring systems and the remote collection of biometric information and highlighting the importance of fairness and privacy protection. While the competence of AI is advancing, skepticism about its warmth also grows. Simultaneously, the emphasis on its warmth and the need for safeguards will increase.

生成性人工智能在近年来已成为人工智能技术中最引人注目的发展,像 GPT 和 Sora 这样的产品在内容生成和分析方面展现了令人印象深刻的能力(杨等,2024)。例如,Sora 创建的视频可以达到难以区分的真实感。甚至大型语言模型也被用来解释其他人工智能模型,从而增强人工智能的可解释性(比尔斯等,2023)。随着人工智能能力的增长,其对社会的影响也在加大,包括潜在的负面影响,例如通过生成性人工智能轻易生成虚假内容。同时,全球各国政府正在推出法律法规,以负责任地引导人工智能的发展。2024 年 3 月 13 日,欧盟通过了人工智能法案,这是全球首个全面的人工智能监管框架(欧洲议会,2024)。该法案根据风险等级对人工智能的使用进行分类,禁止在某些领域使用,如社会评分系统和远程收集生物识别信息,并强调公平性和隐私保护的重要性。 随着人工智能能力的提升,人们对其温暖性的怀疑也在增加。同时,对其温暖性的重视和对安全保障的需求也将增加。

Overall, we review factors influencing trust formation from the user’s perspective via a three-dimension model of trust in AI. The framework, with its detailed examination of factors impacting the trustor, the trustee, and their interaction context, is instrumental in guiding the creation of targeted educational and training programs that are essential for enabling users to understand and engage with AI more effectively. Furthermore, trustworthy AI could benefit from the adoption of trust measurement methods to assess the effectiveness of these initiatives. These assessments should include both subjective self-report methods and objective indicators of engagement with AI technologies, including reliance, compliance, and decision-making behavior and time.

总体而言,我们从用户的角度通过一个三维信任模型审视影响信任形成的因素。该框架详细考察了影响信任者、受信者及其互动背景的因素,对于指导制定针对性的教育和培训项目至关重要,这些项目对于使用户更有效地理解和参与人工智能至关重要。此外,可信的人工智能可以通过采用信任测量方法来评估这些举措的有效性。这些评估应包括主观自我报告方法和与人工智能技术的互动的客观指标,包括依赖、遵从和决策行为及时间。

6 Summary and conclusion 6 摘要与结论

This article provides a comprehensive review and analysis of factors influencing trust in AI and offers insights and suggestions on the development of trustworthy AI. The three-dimension framework of trust is applicable for understanding trust in interpersonal relationships, human-automation interactions, and human-AI systems. The framework can also help understand user needs and concerns, guide the refinement of AI system designs, and aid in the making of policies and guidelines on trustworthy AI. All of these shall lead to AI systems that are more trustworthy, increasing the likelihood for people to accept, adopt, and use them properly.

本文提供了对影响人工智能信任的因素的全面回顾和分析,并对可信赖人工智能的发展提出了见解和建议。三维信任框架适用于理解人际关系、人与自动化交互以及人与人工智能系统中的信任。该框架还可以帮助理解用户需求和关注点,指导人工智能系统设计的完善,并协助制定关于可信赖人工智能的政策和指南。所有这些都将导致更可信赖的人工智能系统,增加人们正确接受、采用和使用它们的可能性。

Author contributions 作者贡献

YL: Writing – original draft. BW: Writing – original draft. YH: Writing – original draft. SL: Writing – review & editing.

YL:撰写 – 原始草稿。BW:撰写 – 原始草稿。YH:撰写 – 原始草稿。SL:撰写 – 审阅与编辑。

Funding 资金

The authors declare financial support was received for the research and publication of this article. This work was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 32171074] and the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences [grant number E1CX0230] awarded to SL.

作者声明本研究及本文章的出版得到了财务支持。本研究得到了中国国家自然科学基金[资助编号 32171074]和中国科学院心理研究所[资助编号 E1CX0230]的研究资助,资助者为 SL。

Acknowledgments 致谢

We thank members of the Risk and Uncertainty Management Lab for their helpful comments and suggestions during the study.

我们感谢风险与不确定性管理实验室的成员在研究期间提供的有益意见和建议。

Conflict of interest 利益冲突

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

作者声明,研究是在没有任何商业或财务关系的情况下进行的,这些关系可能被视为潜在的利益冲突。

Publisher’s note 出版商的说明