Abstract 抽象的

In an era where artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping workplace dynamics, this study addresses the pressing need to understand the intricate relationships between job insecurity, psychological safety, and employee depression. Despite extensive research in this domain, significant gaps remain, particularly in comprehending how technological advancements influence these relationships. This research overcomes these challenges by introducing a novel approach that incorporates the mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating influence of employee self-efficacy in AI use. To empirically test our hypotheses, we employed a stratified random sampling method to collect data from 408 employees across various South Korean firms. Also, we utilized 3 wave time-lagged research design to enhance the robustness of the findings. The results which were based on the structural equation modeling analysis indicate that all study hypotheses are supported. The findings not only bridge a crucial gap in the existing literature but also offer a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological impacts of job insecurity in an AI-integrated work environment. This research marks a significant contribution by elucidating the nuanced mechanisms through which job insecurity affects employee well-being in the context of rapid technological change.

在人工智慧 (AI) 正在重塑工作場所動態的時代,這項研究解決了了解工作不安全感、心理安全感和員工憂鬱之間複雜關係的迫切需求。儘管在這一領域進行了廣泛的研究,但仍存在重大差距,特別是在理解技術進步如何影響這些關係方面。這項研究透過引入一種新穎的方法克服了這些挑戰,該方法結合了心理安全的中介作用和員工自我效能在人工智慧使用中的調節影響。為了實證檢驗我們的假設,我們採用分層隨機抽樣方法收集了韓國各公司 408 名員工的資料。此外,我們也利用了 3 波時滯研究設計來增強研究結果的穩健性。基於結構方程模型分析的結果顯示所有研究假設均得到支持。研究結果不僅彌補了現有文獻中的一個關鍵空白,而且還提供了對人工智慧整合工作環境中工作不安全感的心理影響的更全面的理解。這項研究闡明了在快速技術變革的背景下工作不安全感影響員工福祉的微妙機制,並做出了重大貢獻。

Similar content being viewed by others

其他人正在查看類似內容

Explore related subjects 探索相關主題

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.發現相關學科頂尖研究人員的最新文章、新聞和故事。

使用我們的預提交清單

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

避免手稿中的常見錯誤。

Introduction 介紹

The evolving landscape of modern workplaces, characterized by rapid technological advancements and shifting economic paradigms, presents new challenges in understanding the psychological well-being of employees. This research emerges from a critical need to address gaps in our understanding of how contemporary workplace stressors, particularly job insecurity impact employee mental health (Wu et al., 2022; Yam et al., 2023). The issue of job insecurity has become increasingly salient in recent years, particularly in the context of economic globalization, technological advancements, and the COVID-19 pandemic (Oluwatayo et al., 2022). Job insecurity refers to a perception or fear of losing one’s job and includes feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, and powerlessness (Vander Elst et al., 2016). The prevalence of job insecurity has increased, with many workers experiencing precarious employment conditions, such as temporary contracts, part-time work, and freelance work (Jiang et al., 2022; Langerak et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2021; Peltokorpi & Allen, 2023).

以快速的技術進步和不斷變化的經濟範式為特徵的現代工作場所不斷變化的格局,給理解員工的心理健康帶來了新的挑戰。這項研究的出現是為了解決我們對當代工作場所壓力源,特別是工作不安全感如何影響員工心理健康的理解上的差距(Wu 等人, 2022 年;Yam 等人, 2023 年)。近年來,工作不穩定問題變得越來越突出,特別是在經濟全球化、技術進步和 COVID-19 大流行的背景下(Oluwatayo 等人, 2022 )。工作不安全感是指對失去工作的感覺或恐懼,包括不確定感、焦慮感和無力感(Vander Elst et al., 2016 )。工作不安全感日益普遍,許多工人的就業條件不穩定,例如臨時合約、兼職工作和自由職業(Jiang 等, 2022 年;Langerak 等, 2022 ;Lin 等, 2021 年)佩爾托科皮和艾倫, 2023 )。

Considering the significance of job insecurity in the workplace, many scholars have investigated its influence on employee perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. For example, close associations have been identified between job insecurity, employee well-being, and performance at work, as well as productivity and employee turnover. Additionally, previous studies have consistently reported that job insecurity is a significant stressor that can lead to negative outcomes, such as burnout and increased absenteeism and turnover, as well as decreased job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational identification, organizational trust, work engagement, creativity, innovative behaviors, in-role/extra-role behaviors, intrinsic motivation, and productivity (De Witte et al., 2016; Jiang & Lavaysse, 2018; Jiang et al., 2022; Kim & Kim, 2020; Langerak et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2021; Peltokorpi & Allen, 2023; Richter & Näswall, 2019; Shoss, 2017; Shoss et al., 2023; Sverke et al., 2019; Vander Elst et al., 2016).

考慮到工作場所工作不安全感的重要性,許多學者研究了其對員工認知、態度和行為的影響。例如,工作不安全感、員工福祉、工作績效以及生產力和員工流動率之間有密切關聯。此外,先前的研究一致表明,工作不安全感是一個重大壓力源,可能導致負面結果,例如倦怠、缺勤和流動率增加,以及工作滿意度、組織承諾、組織認同、組織信任、工作投入和創造力道下降。 . , 2022 ;Lin等人, 2021 ; Richter和Näswall , 2017 ;Sverke 等人, 2019 ;等, 2016 )。

As mentioned, although several previous academic studies have investigated the impact of job insecurity on organizational outcomes, significant research gaps remain. First, previous research on job insecurity has given little attention to the importance of employee depression, and only a few studies have addressed the influence of job insecurity on employee depression (Lin et al., 2021; Shoss et al., 2023). Nonetheless, scholars have reported that globally one-fifth of people have experienced depressive symptoms (Aekwarangkoon & Thanathamathee, 2022; Daly & Robinson, 2022; Goodwin et al., 2022; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Rotenstein et al., 2016). Depression is a significant predictor of low psychological adjustment levels and major health issues (Fried et al., 2022; Herrman et al., 2022; Marwaha et al., 2023; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Thapar et al., 2022). Moreover, employee depression can significantly and negatively affect workers’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors, both directly and indirectly (Adler et al., 2006; Birnbaum et al., 2010; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lerner & Henke, 2008; Lin et al., 2018; Rotenstein et al., 2016), so investigating this relationship is essential (Shoss et al., 2023).

如前所述,儘管先前的幾項學術研究調查了工作不安全感對組織成果的影響,但仍存在重大研究空白。首先,以往關於工作不安全感的研究很少關注員工憂鬱的重要性,只有少數研究探討了工作不安全感對員工憂鬱的影響(Lin等, 2021 ;Shoss等, 2023 )。儘管如此,學者報告稱,全球五分之一的人經歷過憂鬱症狀(Aekwarangkoon & Thanathamathee, 2022 ;Daly & Robinson, 2022 ;Goodwin 等, 2022 ;Jacobson & Newman, 2017 ;Lin 等, 2018 ;Rotenstein等 ;Rotenstein等 ;人, 2016 )。憂鬱症是低心理適應程度和重大健康問題的重要預測因子(Fried et al., 2022 ; Herrman et al., 2022 ; Marwaha et al., 2023 ; Jacobson & Newman, 2017 ; Lin et al., 2018 ; Thapar等人, 2022 )。此外,員工憂鬱症會直接或間接地對員工的看法、態度和行為產生顯著的負面影響(Adler 等人, 2006 年;Birnbaum 等人, 2010 年;Evans–Lacko 和 Knapp, 2016 年 2016 年;Jacobson 和Newman, 2017 年) ;Lerner & Henke, 2008 ;Lin 等人, 2018 ;Rotenstein 等人, 2016 ),因此研究這種關係至關重要(Shoss 等人, 2023 )。

Second, few prior studies have examined the job insecurity–employee depression link, and few of the underlying mechanisms (i.e., mediators) and contextual variables (i.e., moderators) of the relationship (Jiang et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2021; Shoss et al., 2023). By identifying these underlying mechanisms and contingent factors, we can better understand, predict, and potentially regulate the influence of job insecurity on depression. Thus, it is crucial to investigate the relationship’s mediating and moderating factors to comprehensively understand this association.

其次,先前很少研究檢視工作不安全感與員工憂鬱之間的聯繫,也很少研究這種關係的潛在機制(即中介因素)和背景變數(即調節因素)(Jiang et al., 2022 ;Lin et al., 2021 ;肖斯等人, 2023 )。透過識別這些潛在機制和偶然因素,我們可以更好地理解、預測和潛在地調節工作不安全感對憂鬱症的影響。因此,研究這種關係的中介和調節因素對於全面理解這種關聯至關重要。

Third, and more importantly, the extant job insecurity research has insufficiently explored employees’ interactions with artificial intelligence (AI) in the workplace (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Tambe et al., 2019). Thus, there are relatively few studies exploring the effects of AI within organizations from the perspective of job insecurity. Although AI’s rise has resulted in revolutionary changes at work, scant research attention has been given to the psychological and social influences of AI in the workplace. Because AI has continuously and rapidly altered traditional ways of performing tasks, it is critical to investigate how technological changes influence employee perceptions and attitudes concerning job insecurity. For example, AI can amplify the negative influences of job insecurity by automating various tasks that traditionally have been performed by humans. In contrast, AI will likely mitigate the negative impact of job insecurity by enabling employees to perform tasks more efficiently and effectively. Therefore, investigating the interactions or the moderating effects of AI from a job-insecurity perspective is necessary.

第三,更重要的是,現有的工作不安全感研究尚未充分探討員工在工作場所與人工智慧(AI)的互動(Ayyagari 等人, 2011 ;Tambe 等人, 2019 )。因此,從工作不安全感的角度探討人工智慧在組織內的影響的研究相對較少。儘管人工智慧的興起為工作帶來了革命性的變化,但人們對人工智慧對工作場所的心理和社會影響的研究卻很少。由於人工智慧持續快速地改變了執行任務的傳統方式,因此研究技術變革如何影響員工對工作不安全感的看法和態度至關重要。例如,人工智慧可以透過自動化傳統上由人類執行的各種任務來放大工作不安全感的負面影響。相較之下,人工智慧可能會讓員工更有效率地執行任務,從而減輕工作不安全感的負面影響。因此,有必要從工作不安全的角度研究人工智慧的相互作用或調節作用。

In light of these gaps, the primary goals of this research are as follows. The first goal is to empirically examine the role of psychological safety as a mediator in the relationship between job insecurity and employee depression. This involves exploring how job insecurity may lead to a reduction in psychological safety, which in turn, could increase the risk of depression among employees. By achieving this goal, the research aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which job insecurity impacts employee well-being. The second goal is to investigate the moderating role of employee self-efficacy in AI use on the relationship between job insecurity and psychological safety. This involves understanding how proficiency and confidence in using AI technologies might buffer the negative psychological impacts of job insecurity. In doing so, the study seeks to illuminate how individual capabilities in AI can influence employees’ perceptions and reactions to job insecurity in a technologically evolving workplace.

鑑於這些差距,本研究的主要目標如下。第一個目標是實證檢驗心理安全在工作不安全感和員工憂鬱之間關係的中介效果。這涉及探討工作不安全感如何導致心理安全感降低,進而可能增加員工憂鬱的風險。透過實現這一目標,該研究旨在更全面地了解工作不安全感影響員工福祉的機制。第二個目標是調查人工智慧使用中員工自我效能感對工作不安全感和心理安全感之間關係的調節效果。這涉及了解使用人工智慧技術的熟練程度和信心如何緩衝工作不安全感的負面心理影響。在此過程中,該研究旨在闡明人工智慧中的個人能力如何影響員工在技術不斷發展的工作場所中對工作不安全感的看法和反應。

The current study addresses these research gaps by examining the impacts of job insecurity on depression and its intermediating procedures (mediators) and contingent variables (moderators). Specifically, we propose that job insecurity might increase depression based on three primary mechanisms that explain the effects of job insecurity on depression: physiological, cognitive, and behavioral perspectives (Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Rotenstein et al., 2016). First, the current paper proposes that job insecurity might reduce psychological safety (Kim, 2020). According to Edmondson (1999) and Kahn (1990), psychological safety involves an individual feeling comfortable expressing themselves without fearing negative reactions that influence their self-image, position, or career. Employees who perceive that their jobs are secure and guaranteed within an organization are more likely to feel psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999; Kahn, 1990; Kim, 2019, 2020).

目前的研究透過研究工作不安全感對憂鬱症的影響及其中介程序(中介)和偶然變數(調節)來彌補這些研究空白。具體來說,我們基於解釋工作不安全感對憂鬱症影響的三種主要機制提出,工作不安全感可能會增加憂鬱症:生理、認知和行為角度(Jacobson & Newman, 2017 ;Lin 等, 2018 ;Rotenstein 等, 2018 )。首先,目前的論文提出工作不安全感可能會降低心理安全感(Kim, 2020 )。根據埃德蒙森(Edmondson, 1999 )和卡恩(Kahn, 1990 )的觀點,心理安全涉及個人在表達自己時感到舒適,而不擔心影響其自我形象、地位或職業的負面反應。認為自己的工作在組織內有保障且有保障的員工更有可能感到心理安全(Edmondson, 1999 ; Kahn , 1990 ;Kim, 2019,2020 )。

Next, this research proposes that decreased psychological safety at work results in an increased risk of depression. Employees who do not feel psychologically safe in their workplace may experience increased job stress, anxiety, and fear, all of which can lead to a wide range of negative mental states, such as depression (Birnbaum et al., 2010; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Newman et al., 2017).

接下來,這項研究提出,工作中心理安全感下降會導致憂鬱風險增加。在工作場所感到心理不安全的員工可能會經歷更大的工作壓力、焦慮和恐懼,所有這些都可能導致各種負面心理狀態,例如憂鬱(Birnbaum 等, 2010 ;Evans–Lacko 和納普, 2016 ;雅各森和紐曼, 2017 ;紐曼等人, 2017 )。

Moreover, and more importantly, this paper suggests that members’ self-efficacy in AI use will mitigate job insecurity's harmful impacts on psychological safety. For instance, workers with high self-efficacy in AI use may more easily adopt and effectively and efficiently utilize new technologies (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Tambe et al., 2019), thereby experiencing a sense of competence and mastery at work (Bandura, 1982). Such a sense of mastery is likely to facilitate feelings of psychological safety because employees would feel more confident in their ability to resolve work-related challenges and uncertainties. These positive perceptions would buffer and decrease the detrimental impact of job insecurity on psychological safety. The significance of this research lies in its potential to bridge these identified gaps. By focusing on the mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of AI self-efficacy, the study offers new insights into the complex dynamics of job insecurity in modern workplaces. This research not only contributes to academic discourse but also provides practical implications for organizational leaders and HR practitioners in managing employee well-being in an age marked by rapid technological change and uncertainty.

此外,更重要的是,本文表明,成員在人工智慧使用中的自我效能將減輕工作不安全感對心理安全的有害影響。例如,在人工智慧使用中自我效能感高的員工可能更容易採用並有效且有效率地利用新技術(Ayyagari et al., 2011 ;Tambe et al., 2019 ),從而在工作中體驗到能力感和掌控感(班杜拉, 1982 )。這種掌控感可能會促進心理安全感,因為員工會對自己解決工作相關挑戰和不確定性的能力更有信心。這些正面的看法將緩衝和減少工作不安全感對心理安全的不利影響。這項研究的意義在於它有可能彌補這些已確定的差距。透過關注心理安全的中介作用和人工智慧自我效能的調節作用,該研究為現代工作場所工作不安全感的複雜動態提供了新的見解。這項研究不僅有助於學術討論,也為組織領導者和人力資源從業人員在技術快速變革和不確定性的時代管理員工福祉提供了實際意義。

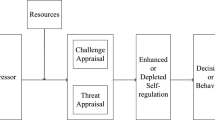

This study is grounded in a conceptual framework that intertwines theories from organizational behavior and psychology, aiming to fill a notable gap in the current understanding of how technological advancements impact employee well-being. The focus is twofold: to elucidate the mediating role of psychological safety in the job insecurity-depression nexus and to examine how employee self-efficacy in AI use moderates this relationship. First, drawing upon the Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) Model (Jex, 1998), the research begins by examining job insecurity as a primary stressor leading to psychological strain and consequent depressive outcomes. The relationship between job insecurity and employee mental health, particularly depression, is well-documented in the literature (e.g., Shoss, 2017; Sverke et al., 2002). However, this study extends this examination by integrating psychological safety as a key mediator in this relationship. Second, the concept of psychological safety, as described by Edmondson (1999), is central to this research. The role of psychological safety in mediating the impact of job stressors on employee outcomes is supported by Kahn’s (1990) psychological conditions of engagement and Deci and Ryan's (2000) Self-Determination Theory. This study seeks to empirically test and extend these theoretical propositions within the context of job insecurity and depression. Lastly, Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory (1977) provides the foundation for understanding how an individual’s belief in their capabilities, particularly in using AI, can influence their psychological responses to job insecurity. The moderating role of self-efficacy in AI use is a novel approach in this field and is informed by the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), which emphasizes the importance of perceived ease of use and usefulness in technology adoption.

這項研究建立在一個概念框架的基礎上,該框架將組織行為和心理學的理論交織在一起,旨在填補當前對技術進步如何影響員工福祉的理解中的顯著差距。重點有二:闡明心理安全感在工作不安全感與憂鬱關係中的中介作用,並研究人工智慧使用中員工的自我效能感如何調節這種關係。首先,利用壓力源-壓力-結果(SSO)模型(Jex, 1998 ),研究首先將工作不安全感視為導致心理壓力和隨之而來的憂鬱結果的主要壓力源。工作不安全感與員工心理健康(特別是憂鬱症)之間的關係在文獻中有詳細記載(例如,Shoss, 2017 ;Sverke 等, 2002 )。然而,這項研究透過將心理安全作為這種關係中的關鍵中介因素來擴展這項檢查。其次,埃德蒙森(Edmondson, 1999 )所描述的心理安全概念是本研究的核心。 Kahn ( 1990 ) 的敬業心理條件以及 Deci 和 Ryan ( 2000 ) 的自我決定理論支持心理安全在調節工作壓力源對員工結果的影響中的作用。本研究試圖在工作不安全和憂鬱的背景下實證檢驗和擴展這些理論命題。最後,班杜拉的自我效能理論( 1977 )為理解個人對其能力(尤其是使用人工智慧的能力)的信念如何影響他們對工作不安全感的心理反應提供了基礎。 自我效能在人工智慧使用中的調節作用是該領域的一種新穎方法,並受到技術接受模型(Davis, 1989 )的啟發,該模型強調了感知易用性和有用性在技術採用中的重要性。

To summarize the above, existing literature has extensively explored the direct effects of job insecurity on various psychological outcomes, including employee depression. However, there is a conspicuous paucity of research examining the intricate mechanisms through which these effects are mediated and moderated. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating not only the direct impact of job insecurity on depression but also how this relationship is mediated by psychological safety – a concept representing an individual’s perception of being safe to take risks and express oneself in the workplace. Moreover, the research extends to examine how employee self-efficacy in AI use, a critical skill in the contemporary technology-driven work environment, moderates this relationship. By integrating theoretical models such as Self-Efficacy Theory, the Technology Acceptance Model, and the Job Demands-Resources Model, this study offers a novel perspective in understanding these dynamics. The research advances knowledge in the field by (1) elucidating the complex interplay between job insecurity, psychological safety, and employee depression, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological impacts of job insecurity, (2) highlighting the role of employee self-efficacy in AI use as a significant moderating factor, thereby recognizing the importance of individual capabilities in adapting to technological advancements in the workplace, and (3) providing empirical evidence to support theoretical frameworks in a contemporary context, thereby bridging the gap between theory and the evolving realities of modern work environments.

綜上所述,現有文獻廣泛探討了工作不安全感對各種心理結果(包括員工憂鬱症)的直接影響。然而,目前對調節和調節這些影響的複雜機制的研究明顯較少。這項研究旨在填補這一空白,不僅調查工作不安全感對憂鬱症的直接影響,還調查這種關係如何透過心理安全感來調節——心理安全感代表了個人對在工作場所安全地冒險和表達自己的看法。此外,該研究也探討了員工在人工智慧使用中的自我效能感(當代科技驅動的工作環境中的一項關鍵技能)如何調節這種關係。透過整合自我效能理論、技術接受模型和工作需求資源模型等理論模型,本研究為理解這些動態提供了一個新穎的視角。研究透過以下方式增進了該領域的知識:(1)闡明工作不安全感、心理安全感和員工憂鬱之間複雜的相互作用,從而更全面地了解工作不安全感的心理影響,(2)強調員工自我保護的角色人工智慧使用的有效性作為一個重要的調節因素,從而認識到個人能力在適應工作場所技術進步方面的重要性,以及(3)提供經驗證據來支持當代背景下的理論框架,從而彌合理論與現實之間的差距現代工作環境不斷變化的現實。

Given the identified research gaps, this study presents three notable contributions to the literature on job insecurity and depression. First, it expands the extant scholarship on job insecurity by probing its influence on employee depression, a topic that until now remains largely unaddressed (Lin et al., 2021; Shoss et al., 2023). By evaluating this association, this analysis offers valuable revelations regarding the ramifications of job insecurity vis-à-vis employee mental health, which, in turn, both directly and indirectly affects their perceptions, attitudes, and conduct within the workplace (Adler et al., 2006; Birnbaum et al., 2010; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lerner & Henke, 2008; Lin et al., 2018; Rotenstein et al., 2016).

鑑於已發現的研究空白,本研究對工作不安全感和憂鬱症的文獻提出了三項顯著貢獻。首先,它透過探討工作不安全感對員工憂鬱的影響,擴大了現有的關於工作不安全感的學術研究,而這個主題到目前為止在很大程度上仍未解決(Lin 等人, 2021 ;Shoss 等人, 2023 )。透過評估這種關聯,分析提供了關於工作不安全感與員工心理健康的影響的寶貴啟示,而這反過來又直接或間接影響他們在工作場所的看法、態度和行為(Adler 等人,2017 ) 。

Second, this inquiry elucidates the fundamental mechanisms (i.e., mediators) and contingent variables (i.e., moderators) that form the nexus between job insecurity and employee depression (Lin et al., 2021; Shoss et al., 2023). By clarifying these mediating and moderating factors, this research facilitates a more holistic understanding of operational dynamics, thereby facilitating enhanced prognoses and the potential modulation of the impact of job insecurity on depression.

其次,這項調查闡明了形成工作不安全感和員工憂鬱之間聯繫的基本機制(即中介變數)和偶然變數(即調節變數)(Lin et al., 2021 ;Shoss et al., 2023 )。透過闡明這些中介和調節因素,本研究有助於更全面地理解運作動態,從而促進改善預後並潛在調節工作不安全感對憂鬱症的影響。

Third, this investigation redresses a striking absence in the literature by scrutinizing the interplay between job insecurity and the advent of AI within the workplace. This examination is of particular pertinence and currency given AI technology’s rapid evolution and its concomitant transformation of work procedures and task execution (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Tambe et al., 2019). Furthermore, research has largely overlooked the psychological and societal ramifications of AI on employees. By analyzing the moderating function of AI in the job insecurity–employee depression nexus, this research illuminates both potential positive and adverse outcomes of AI incorporation within organizations and yields a more sophisticated understanding of the intricate dynamics between job insecurity and AI.

第三,這項調查透過仔細研究工作不安全感與人工智慧在工作場所的出現之間的相互作用,彌補了文獻中的一個顯著缺失。鑑於人工智慧技術的快速發展以及隨之而來的工作程序和任務執行的轉變,這種檢查具有特別的針對性和流行性(Ayyagari 等人, 2011 ;Tambe 等人, 2019 )。此外,研究在很大程度上忽略了人工智慧對員工的心理和社會影響。透過分析人工智慧在工作不安全感與員工憂鬱關係中的調節功能,這項研究闡明了人工智慧在組織中納入的潛在正面和不利結果,並對工作不安全感和人工智慧之間錯綜複雜的動態關係有了更深入的理解。

Furthermore, this study distinctively contributes to the existing literature by providing a nuanced exploration of the moderating role of employee self-efficacy in AI use within the job insecurity-psychological safety relationship, an area that has received limited scholarly attention. Unlike previous research that primarily focuses on the direct effects of job insecurity on psychological outcomes, this study delves into the intricacies of how personal capabilities in AI usage can buffer the detrimental impact of job insecurity on psychological safety. By integrating and applying theoretical models such as Self-Efficacy Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model in a novel context, this research not only broadens the understanding of job insecurity implications but also illuminates the potential of individual skill proficiency as a mitigating factor in contemporary technology-driven work environments. Consequently, this study offers a unique perspective in understanding the dynamics of psychological safety in an era marked by rapid technological advancements and shifting job securities.

此外,這項研究對現有文獻做出了獨特的貢獻,它對員工自我效能感在工作不安全感-心理安全關係中人工智慧使用中的調節作用進行了細緻入微的探索,而這個領域受到的學術關注有限。與先前主要關注工作不安全感對心理結果的直接影響的研究不同,這項研究深入探討了人工智慧使用中的個人能力如何緩衝工作不安全感對心理安全的不利影響的複雜性。透過在新穎的背景下整合和應用自我效能理論和技術接受模型等理論模型,這項研究不僅拓寬了對工作不安全感影響的理解,而且闡明了個人技能熟練程度作為當代技術緩解因素的潛力。驅動的工作環境。因此,這項研究為理解這個以技術快速進步和工作保障不斷變化為特徵的時代的心理安全動態提供了獨特的視角。

Theory and hypotheses 理論和假設

Job insecurity and depression

工作不安全感和憂鬱

This paper proposes that job insecurity will increase employee depression. While few studies have investigated the influence of job insecurity on depression, an association between the variables is expected based on the previous research. Job insecurity refers to the feeling of uncertainty or concern that employees experience regarding the future of their employment and whether they will keep their jobs (Vander Elst et al., 2016). Scholars have identified job insecurity as a significant stressor that can adversely affect an employee’s psychological state (Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Jiang et al., 2022; Langerak et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2021; Peltokorpi & Allen, 2023; Shoss, 2017; Shoss et al., 2023). Among various psychological states, we focus on employee depression, which is the most common workplace illness (Lin et al., 2018; Rotenstein et al., 2016). Research has shown that depression relates negatively to employee adjustment, social relationships, productivity, and workplace performance (Adler et al., 2006; Birnbaum et al., 2010; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lerner & Henke, 2008; Lin et al., 2018; Rotenstein et al., 2016).

本文提出,工作不安全感會增加員工的憂鬱情緒。雖然很少有研究調查工作不安全感對憂鬱症的影響,但根據先前的研究預期變數之間存在關聯。工作不安全感是指員工對自己就業的未來以及是否會保住工作感到不確定或擔憂(Vander Elst et al., 2016 )。學者認為,工作不安全感是一種重大壓力源,會對員工的心理狀態產生不利影響(Jacobson & Newman, 2017 ;Jiang et al., 2022 ;Langerak et al., 2022 ;Lin et al., 2021 ;Peltokorpi & Allen, 2023) ;肖斯, 2017 ;肖斯等人, 2023 )。在各種心理狀態中,我們將重點放在員工憂鬱症,這是最常見的職場疾病(Lin et al., 2018 ;Rotenstein et al., 2016 )。研究表明,憂鬱症與員工適應、社會關係、生產力和工作場所績效呈負相關(Adler 等人, 2006 年;Birnbaum 等人, 2010 年;Evans–Lacko 和 Knapp, 2016 年;Jacobson 和 Newman, 2017 年;Lerner 和Henke, 2008 ;Lin 等人, 2018 ;Rotenstein 等人, 2016 )。

Based on the literature on depression, three primary mechanisms that influence job insecurity’s impact on depression are suggested: physiological, cognitive, and behavioral perspectives (Daly & Robinson, 2022; Friedet al., 2022; Goodwin et al., 2022; Herrman et al., 2022; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Marwaha et al., 2023; Rotenstein et al., 2016). First, physiological mechanisms suggest that job insecurity may lead to chronic stress, activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), eventually causing increased cortisol levels and other physiological changes that contribute to depression. Second, cognitive mechanisms impacting job insecurity result in negative cognitive appraisals, such as feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and a perceived lack of control over one’s situation. These can cause negative emotions and depressive symptoms (Bhattacharya et al., 2023). Finally, behavioral mechanisms explain that job insecurity can lead to maladaptive coping behaviors, such as avoidance, withdrawal, and substance abuse, which directly influence the development and persistence of depression. Therefore, we focus and rely on cognitive mechanisms to hypothesize that an unstable job will significantly increase an employee’s depression.

根據有關憂鬱症的文獻,提出了影響工作不安全感對憂鬱症影響的三種主要機制:生理、認知和行為觀點(Daly & Robinson, 2022 ;Friedet al., 2022 ;Goodwin 等人, 2022 ; Herrman 等) ., 2022 ;Jacobson和Newman, 2017 ;Marwaha 等, 2023 ;Rotenstein 等, 2016 。首先,生理機製表明,工作不安全感可能導致慢性壓力,激活下丘腦-垂體-腎上腺(HPA)軸和交感神經系統(SNS),最終導致皮質醇水平升高和其他導致憂鬱的生理變化。其次,影響工作不安全感的認知機制會導致負面的認知評估,例如無助感、絕望感以及對自己的處境缺乏控制的感覺。這些可能會導致負面情緒和憂鬱症狀(Bhattacharya et al., 2023 )。最後,行為機制解釋說,工作不安全感會導致適應不良的應對行為,如迴避、退縮和藥物濫用,這直接影響憂鬱症的發展和持續。因此,我們關注並依賴認知機制來假設不穩定的工作會顯著增加員工的憂鬱程度。

Furthermore, this paper seeks to provide a theoretical foundation for understanding how job insecurity influences employee depression, drawing upon established psychological and organizational theories. At the core of the relationship between job insecurity and depression is the concept of stress. Stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) posits that individuals appraise potential stressors in their environment and respond based on their perceived ability to cope with these stressors. Job insecurity, characterized as a significant workplace stressor, is perceived by employees as a threat to their employment continuity, provoking a stress response. This chronic stress state, if persistent, can lead to symptoms of depression (Sverke et al., 2002).

此外,本文試圖利用現有的心理學和組織理論,為理解工作不安全感如何影響員工憂鬱症提供理論基礎。工作不安全感和憂鬱症之間關係的核心是壓力的概念。壓力理論(Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 )認為,個人評估其環境中的潛在壓力源,並根據他們應對這些壓力源的感知能力做出反應。工作不安全感被認為是一種重要的工作場所壓力源,被員工視為對其就業連續性的威脅,從而引發壓力反應。這種慢性壓力狀態如果持續存在,可能會導致憂鬱症狀(Sverke et al., 2002 )。

Next, Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll, 1989) provides a lens to understand the psychological impact of job insecurity. It suggests that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect their valued resources. Job insecurity threatens these resources, not only in terms of actual job loss but also in the perceived loss of career opportunities, social status, and financial stability. The anticipation or experience of resource loss can lead to psychological strain, manifesting as depression (Halbesleben et al., 2014).

接下來,資源保護(COR)理論(Hobfoll, 1989 )提供了一個理解工作不安全感的心理影響的觀點。它表明個人努力獲取、保留和保護他們寶貴的資源。工作不安全感威脅這些資源,不僅體現在實際失業方面,也體現在人們認為的職業機會、社會地位和財務穩定性的喪失。對資源損失的預期或經驗可能會導致心理緊張,表現為憂鬱(Halbesleben et al., 2014 )。

Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) also offers a framework for understanding how job characteristics (demands and resources) affect employee well-being. Job insecurity is conceptualized as a job demand that exhausts an employee’s mental and emotional resources, leading to burnout and subsequently depression. The persistent worry about job stability can deplete psychological resources, such as a sense of control and security, increasing the vulnerability to depression (De Witte et al., 2016).

工作需求-資源 (JD-R) 模型(Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 )也提供了一個框架,用於理解工作特徵(需求和資源)如何影響員工福祉。工作不安全感被概念化為一種工作需求,它會耗盡員工的精神和情感資源,導致倦怠和隨後的憂鬱。對工作穩定性的持續擔憂會耗盡心理資源,例如控制感和安全感,從而增加憂鬱症的可能性(De Witte et al., 2016 )。

Lastly, Psychological contract theory (Rousseau, 1995) suggests that there is an unwritten set of expectations between the employee and the employer. Job insecurity can lead to a perceived breach of this psychological contract, especially when employees feel that their job security is compromised despite their commitment to the organization. Such perceived breaches can lead to feelings of betrayal and unfairness, contributing to emotional distress and depressive symptoms (Staufenbiel & König, 2010). Based on the above arguments, we propose this hypothesis.

最後,心理契約理論(Rousseau, 1995 )表明,員工和雇主之間存在著一套不成文的期望。工作不安全感可能會導致這種心理契約被感知到的違反,特別是當員工感到儘管他們對組織做出承諾,但他們的工作安全感受到損害時。這種感知到的違規行為可能會導致背叛和不公平的感覺,從而導致情緒困擾和憂鬱症狀(Staufenbiel & König, 2010 )。基於以上論證,我們提出這個假設。

-

Hypothesis 1: Job insecurity will increase employee depression.

假設1:工作不安全感會增加員工憂鬱情緒。

Job insecurity and psychological safety

工作不安全感和心理安全感

This paper proposes that job insecurity will decrease employees’ psychological safety (Kim, 2020). Although relatively few studies have examined the association between job insecurity and psychological safety among employees (Shoss et al., 2023), Edmondson (1999) and Kahn (1990) found that job insecurity negatively impacts employee's perceived psychological safety. Psychological safety refers to employees’ perceived comfort in expressing themselves or taking actions without fearing adverse outcomes affecting their self-image, position, or career (Kahn, 1990; Newman et al., 2017). Employees who perceive that their jobs are secure and guaranteed within an organization are more likely to feel psychologically safe. This sense of safety allows them to address significant issues and take risks without fear of rejection or criticism from colleagues or the organization, as proposed by Edmondson (1999). This increased psychological safety also encourages employees to communicate more openly and seek help from peers because they trust that their colleagues will not harm them (Kim, 2020).

本文提出工作不安全感會降低員工的心理安全感(Kim, 2020 )。儘管相對較少的研究探討了員工的工作不安全感和心理安全感之間的關聯(Shoss等, 2023 ),但Edmondson( 1999 )和Kahn( 1990 )發現工作不安全感會對員工的心理安全感產生負面影響。心理安全是指員工在表達自己或採取行動時感到舒適,而不擔心影響其自我形象、職位或職業的不利結果(Kahn, 1990 ;Newman 等, 2017 )。認為自己的工作在組織內有保障並有保障的員工更有可能在心理上感到安全。正如埃德蒙森(Edmondson, 1999 )所提出的,這種安全感使他們能夠解決重大問題並承擔風險,而不必擔心同事或組織的拒絕或批評。這種增加的心理安全感也鼓勵員工更公開地溝通並向同事尋求幫助,因為他們相信同事不會傷害他們(Kim, 2020 )。

In contrast, it is challenging for employees to maintain their authentic selves when they perceive their jobs to be insecure because they fear abandonment (Edmondson, 1999; Kahn, 1990). In such uncertain conditions, employees are likely to feel psychological burdens and pressures, and a need to perform perfectly to prevent rejection by the organization. Consequently, they may avoid raising uncomfortable yet essential organizational issues, or they may respond passively by concealing or ignoring such concerns to avoid being attacked by colleagues (Edmondson, 1999; Kahn, 1990; Kim, 2019). Moreover, when employees experience job insecurity, they are less likely to ask for help from colleagues, fearing that others may perceive them as incapable. Additionally, they tend to view their colleagues as potential obstacles or competition to their job security (Edmondson, 1999; Kahn, 1990; Kim, 2019).

相較之下,當員工因為害怕被拋棄而認為自己的工作沒有保障時,要保持真實的自我就很困難(Edmondson, 1999 ;Kahn, 1990 )。在這種不確定的情況下,員工可能會感到心理負擔和壓力,並且需要完美地表現以防止被組織拒絕。因此,他們可能會避免提出令人不安但重要的組織問題,或者他們可能會透過隱瞞或忽略此類問題來被動應對,以避免受到同事的攻擊(Edmondson, 1999 ;Kahn, 1990 ;Kim, 2019 ) 。此外,當員工遇到工作不穩定時,他們不太可能向同事尋求幫助,因為擔心其他人可能會認為他們無能。此外,他們傾向於將同事視為工作保障的潛在障礙或競爭者(Edmondson, 1999 ;Kahn, 1990 ;Kim, 2019 )。

Furthermore, this paper aims to elucidate this relationship by drawing upon relevant theoretical frameworks. First, conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) posits that individuals strive to protect their valued resources, which include personal characteristics, objects, conditions, or energies. Job insecurity represents a potential threat to an employee’s valued resources, such as job stability and future career prospects. The anticipation of resource loss can lead to a state of heightened vigilance and chronic stress, eroding the sense of safety and security in the workplace. This theoretical perspective helps explain why employees experiencing job insecurity may also report lower levels of psychological safety (Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007).

此外,本文旨在利用相關理論架構來闡明這種關係。首先,資源守恆(COR)理論(Hobfoll, 1989 )假設個人努力保護他們寶貴的資源,包括個人特徵、物體、條件或能量。工作不安全感對員工的寶貴資源(例如工作穩定性和未來職業前景)構成潛在威脅。對資源損失的預期可能會導致高度警覺和長期壓力,從而削弱工作場所的安全感。這個理論觀點有助於解釋為什麼經歷工作不安全感的員工也可能報告較低的心理安全感(Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007 )。

Next, Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs framework (Maslow, 1943) suggests that safety needs, which include security and stability, are fundamental for individuals. When job insecurity threatens these needs, it can impede an employee's ability to fulfill higher-order needs, such as belongingness or esteem. This unfulfilled need for security can undermine psychological safety, as employees may feel exposed to potential harm or loss in the workplace (Maslow, 1943).

接下來,馬斯洛的需求層次架構(Maslow, 1943 )表明,安全需求,包括保障和穩定,是個人的基本需求。當工作不安全感威脅到這些需求時,它可能會妨礙員工滿足更高層次需求的能力,例如歸屬感或尊重。這種未滿足的安全需求可能會破壞心理安全,因為員工可能會感到在工作場所面臨潛在的傷害或損失(Maslow, 1943 )。

Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) also supports the relationship. In the JD-R model, job demands are aspects of the job that require sustained effort and are associated with physiological and psychological costs. Job insecurity can be seen as a significant job demand that exhausts an employee's mental resources and hinders their ability to feel safe and secure in their work environment. Consequently, high job demands, such as persistent insecurity, can diminish an employee's psychological safety by overwhelming their coping capabilities (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

工作需求-資源 (JD-R) 模型(Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 )也支持這種關係。在JD-R模型中,工作需求是工作中需要持續努力並與生理和心理成本相關的方面。工作不安全感可以被視為一種重要的工作需求,它會耗盡員工的心智資源並阻礙他們在工作環境中感到安全和有保障的能力。因此,高工作要求,例如持續的不安全感,可能會壓倒員工的應對能力,從而降低他們的心理安全感(Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 )。

Lastly, uncertainty management theory (Lind & Van den Bos, 2002) highlights how people react to uncertainty in their environment. Job insecurity inherently involves uncertainty regarding the continuity and stability of employment. This uncertainty can lead to a lack of psychological safety as employees are unable to predict and manage future job-related outcomes, leading to feelings of helplessness and vulnerability (Lind & Van den Bos, 2002). Relying on such logic, this paper hypothesizes that job insecurity can significantly impair employee psychological safety.

最後,不確定性管理理論(Lind & Van den Bos, 2002 )強調了人們如何應對環境中的不確定性。工作不安全感本質上涉及就業連續性和穩定性的不確定性。這種不確定性可能會導致缺乏心理安全感,因為員工無法預測和管理未來與工作相關的結果,從而導致無助和脆弱的感覺(Lind&Van den Bos, 2002 )。基於這樣的邏輯,本文假設工作不安全感會顯著損害員工的心理安全。

-

Hypothesis 2: Employee job insecurity decreases their perceived psychological safety.

假設2:員工工作不安全感降低了他們的心理安全感。

Psychological safety and depression

心理安全與憂鬱

This paper proposes that an employee’s decreased psychological safety would increase the severity of their depression. Although the effect of psychological safety on depression at work has been a topic of growing interest among scholars due to its theoretical importance, few researchers have investigated the impact of psychological safety on depression (Edmondson, 1999; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Kahn, 1990).

本文提出,員工心理安全感下降會增加他們憂鬱的嚴重程度。儘管心理安全對工作中憂鬱的影響因其理論重要性而成為學者們日益關注的話題,但很少有研究人員調查心理安全對憂鬱的影響(Edmondson, 1999 ;Evans-Lacko & Knapp, 2016 ;Jacobson &紐曼, 2017 ;卡恩, 1990 )。

Psychological safety is dependent upon the level of confidence an individual employee has in expressing themself without fear of negative consequences, such as rejection or punishment (Edmondson, 1999; Kahn, 1990). Researchers have shown that depression is a common mental health disorder that negatively influences individuals’ emotions, behaviors, and daily functions (Birnbaum et al., 2010; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017). Although existing literature on the effects of perceived psychological safety on depression in the workplace is scant, this paper predicts that employees who feel low levels of psychological safety are more likely to experience increased depression (Edmondson, 1999; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Kahn, 1990; Shields, 2006).

心理安全取決於員工個人表達自己的信心程度,而不必擔心拒絕或懲罰等負面後果(Edmondson, 1999 ;Kahn, 1990 )。研究人員表明,憂鬱症是一種常見的心理健康障礙,會對個人的情緒、行為和日常功能產生負面影響(Birnbaum 等, 2010 ;Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016 ;Jacobson & Newman, 2017 )。儘管關於工作場所心理安全感對憂鬱症影響的現有文獻很少,但本文預測,心理安全感較低的員工更有可能經歷憂鬱症的加重(Edmondson, 1999 ;Evans-Lacko & Knapp, 2016 ;雅各布森和紐曼, 2017 ;卡恩, 1990 ; 2006 )。

This study also suggests that the absence of psychological safety in the workplace increases the risk of depression. Employees who do not feel psychologically safe in the workplace may experience increased levels of job stress, anxiety, and fear, which can lead to a variety of negative mental states, such as depression (Birnbaum et al., 2010; Daly & Robinson, 2022; Goodwin et al., 2022; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Friedet al., 2022; Herrman et al., 2022; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Marwaha et al., 2023). Moreover, insufficient psychological safety would limit employees’ capability or willingness to seek help, share their concerns, and engage in open communication with colleagues and supervisors, eventually resulting in feelings of isolation and depression (Adler et al., 2006; Birnbaum et al., 2010; Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lerner & Henke, 2008; Lin et al., 2018; Rotenstein et al., 2016).

這項研究還表明,工作場所缺乏心理安全感會增加憂鬱症的風險。在工作場所感到心理不安全的員工可能會經歷更高程度的工作壓力、焦慮和恐懼,這可能導致各種負面心理狀態,例如憂鬱(Birnbaum 等, 2010 ;Daly 和 Robinson, 2022) ; Goodwin 等人,2022 年;Friedet 等人,2022 年;Jacobson 和Newman 等人,2018 年; Marwaha等人, 2023 年。此外,心理安全感不足會限制員工尋求協助、分享擔憂以及與同事和主管進行公開溝通的能力或意願,最終導致孤立感和憂鬱感(Adler et al., 2006 ; Birnbaum et al., 2006)。 , 2010 ; Jacobson和 Newman, 2008 ;Rotenstein 等, 2016 ;

We seek to provide solid theoretical foundations to comprehend the association. It is essential to anchor the discussion in relevant theoretical frameworks that elucidate how psychological safety, or the lack thereof, can influence depressive symptoms in employees.

我們尋求提供堅實的理論基礎來理解該協會。有必要將討論錨定在相關的理論框架中,以闡明心理安全或缺乏心理安全如何影響員工的憂鬱症狀。

First, self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2013) posits that fulfilling basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness is crucial for psychological health and well-being. Psychological safety in the workplace fosters an environment where these needs can be met, as employees feel free to express themselves, take risks without fear of negative repercussions, and connect meaningfully with their work and colleagues. Conversely, when psychological safety is lacking, these needs are thwarted, leading to negative psychological outcomes, including depression (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

首先,自我決定理論(Deci & Ryan, 2013 )認為,滿足自主性、能力和關聯性的基本心理需求對於心理健康和福祉至關重要。工作場所的心理安全營造了一個可以滿足這些需求的環境,因為員工可以自由表達自己,承擔風險而不用擔心負面影響,並與工作和同事建立有意義的聯繫。相反,當缺乏心理安全感時,這些需求就會受到阻礙,導致負面的心理結果,包括憂鬱症(Ryan & Deci, 2000 )。

Next, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory (Maslow, 1943) emphasizes the importance of safety needs, which include security, stability, and freedom from fear. In a work environment where psychological safety is compromised, employees may feel insecure and anxious, impeding their ability to fulfill higher-order needs such as belongingness and esteem. This unmet need for safety and security can contribute to the development of depressive symptoms (Maslow, 1943).

其次,馬斯洛的需求層次理論(Maslow, 1943 )強調了安全需求的重要性,其中包括保障、穩定和免於恐懼的自由。在心理安全受到損害的工作環境中,員工可能會感到不安全和焦慮,從而妨礙他們滿足歸屬感和尊重等更高層次需求的能力。這種對安全和保障的未滿足的需求可能會導致憂鬱症狀的發展(Maslow, 1943 )。

Also, according to the JD-R model, job resources (such as psychological safety) can buffer the impact of job demands on stress and burnout, which are closely linked to depression. Psychological safety can be viewed as a vital job resource that helps employees cope with job demands. Its absence can lead to heightened stress and burnout, potentially culminating in depressive symptoms (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

此外,根據JD-R模型,工作資源(如心理安全)可以緩衝工作需求對壓力和倦怠的影響,而壓力和倦怠與憂鬱密切相關。心理安全可以被視為幫助員工應對工作需求的重要工作資源。它的缺失會導致壓力和倦怠加劇,最終可能導致憂鬱症狀(Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 )。

And, attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) suggests that secure attachments are critical for psychological well-being. In the workplace, psychological safety can foster a sense of secure attachment, where employees feel supported and valued. A lack of psychological safety might mirror insecure attachment, leading to feelings of isolation, anxiety, and depression (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

而且,依附理論(Bowlby, 1969 )表明,安全依附對於心理健康至關重要。在工作場所,心理安全可以培養安全依附感,讓員工感到被支持和重視。缺乏心理安全感可能反映出不安全的依戀,導致孤立、焦慮和憂鬱的感覺(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007 )。

Lastly, social support theory (Cobb, 1976) also bolster our argument. Social support in the workplace, which is closely tied to the concept of psychological safety, is known to be a buffer against stress and depression. A psychologically safe environment fosters positive social interactions and support among colleagues, which can protect against depressive symptoms. In contrast, a lack of psychological safety may lead to inadequate social support, exacerbating the risk of depression (Cobb, 1976).

最後,社會支持理論(Cobb, 1976 )也支持了我們的論點。工作場所的社會支持與心理安全的概念密切相關,眾所周知,它可以緩衝壓力和憂鬱。心理安全的環境可以促進同事之間的積極社交互動和支持,從而預防憂鬱症狀。相反,缺乏心理安全感可能會導致社會支持不足,從而加劇憂鬱症的風險(Cobb, 1976 )。

Creating a psychologically safe work environment is critical for enhancing employee mental health and overall outcomes. An organization that prioritizes improving its employees’ psychological safety creates a culture of openness, trust, and respect, thereby decreasing the risk of depression among employees. Furthermore, by establishing a work environment in which employees feel free to express their ideas authentically, share their concerns, and seek help, the organization both diminishes the harmful effects of psychological stress originating from job insecurity and facilitates employee well-being. Therefore, the link between psychological safety and depression emphasizes the importance of building a safe workplace that supports employee mental health. Relying on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis.

創造一個心理安全的工作環境對於增強員工的心理健康和整體成果至關重要。一個優先考慮改善員工心理安全的組織會創造一種開放、信任和尊重的文化,從而降低員工憂鬱的風險。此外,透過建立一個讓員工可以自由真實地表達自己的想法、分享自己的擔憂和尋求幫助的工作環境,組織既可以減少因工作不安全感而產生的心理壓力的有害影響,又可以促進員工的福祉。因此,心理安全與憂鬱之間的關聯強調了建立支持員工心理健康的安全工作場所的重要性。基於這些論點,我們提出以下假設。

-

Hypothesis 3: Decreased psychological safety increases the degree of employee depression.

假設3:心理安全感下降會增加員工憂鬱程度。

Mediation of psychological safety in the job insecurity–depression link

工作不安全感與憂鬱連結中心理安全感的中介作用

We propose that the degree of employee psychological safety might play a mediating role in the job insecurity–depression link. An integrated theoretical framework, as evidenced by the earlier detailed exploration in this paper, fundamentally addresses how diverse theoretical concepts combine to explain a particular phenomenon. In this case, such an integrated framework would denote the interconnected relationships between job insecurity, psychological safety, and depression. The framework borrows from prior empirical findings and theoretical foundations to construct a comprehensive explanation of how these three concepts interact; thus, providing an in-depth perspective on the influences and outcomes of job insecurity on employee depression.

我們認為,員工心理安全程度可能在工作不安全感與憂鬱之間發揮中介效果。正如本文早期的詳細探索所證明的,一個綜合的理論架構從根本上解決了不同的理論概念如何結合起來解釋特定現象的問題。在這種情況下,這樣一個綜合框架將表示工作不安全感、心理安全感和憂鬱症之間的相互關聯的關係。該框架借鑒了先前的實證研究結果和理論基礎,對這三個概念如何相互作用建構了全面的解釋;因此,深入了解工作不安全感對員工憂鬱症的影響和結果。

The initial aspect of this integrated framework focuses on job insecurity and its impact on employee depression. Job insecurity, as defined by Vander Elst et al. (2016), implies the subjective perception of threatened job loss or uncertainty concerning job continuity. Research suggests that job insecurity acts as a significant stressor, potentially leading to adverse psychological states, including depression (Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lin et al., 2021; Shoss, 2017; Shoss et al., 2023). It has examined job insecurity as a catalyst for increased depression and also as a detriment of employee psychological safety. Furthermore, prior research has theorized that decreased psychological safety may lead to exacerbated depression levels. The argument combines concepts from organizational behavior and occupational health psychology, underscoring the significance of understanding these variables in an interconnected manner, rather than as discrete phenomena.

這個綜合框架的最初面向著重於工作不安全感及其對員工憂鬱症的影響。工作不安全感,由 Vander Elst 等人定義。 ( 2016 ),暗示了對失業威脅或工作連續性不確定性的主觀看法。研究表明,工作不安全感是一種重要的壓力源,可能導致不良心理狀態,包括憂鬱(Jacobson & Newman, 2017 ;Lin 等, 2021 ;Shoss, 2017 ;Shoss 等, 2023 )。報告將工作不安全感視為導致憂鬱症加劇的催化劑,同時也損害了員工的心理安全。此外,先前的研究認為,心理安全感下降可能會導致憂鬱程度加劇。這個論點結合了組織行為和職業健康心理學的概念,強調了以相互關聯的方式而不是離散現象來理解這些變數的重要性。

Job insecurity is presented as a significant work-related stressor capable of negatively impacting employees' psychological well-being. It denotes the perception of uncertainty regarding one's employment continuity and stability. This uncertainty, born of real or imagined threats to job security, is suggested to directly influence depression levels among employees. Depression is a mental health condition prevalent in the workplace and is known to compromise employee adjustment, social relationships, productivity, and performance. The proposition that job insecurity increases depression pivots on three key mechanisms: physiological, cognitive, and behavioral.

工作不安全感被認為是一種與工作相關的重要壓力源,能夠對員工的心理健康產生負面影響。它表示對一個人就業連續性和穩定性的不確定性的看法。這種由真實或想像的工作保障威脅所產生的不確定性被認為會直接影響員工的憂鬱程度。憂鬱症是一種在工作場所普遍存在的心理健康狀況,已知會影響員工的適應能力、社會關係、生產力和績效。工作不安全感會增加憂鬱症的觀點主要基於三個關鍵機制:生理、認知和行為。

Physiologically, chronic stress induced by job insecurity could over-stimulate the HPA axis and the SNS, leading to increased cortisol levels and other physiological alterations associated with depression. Cognitive mechanisms suggest that insecurity in employment might precipitate negative cognitive appraisals, such as feelings of helplessness and lack of control, which in turn may evoke depressive symptoms. Lastly, behavioral mechanisms imply that job insecurity could instigate maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance, withdrawal, and substance abuse, which may contribute to the onset and persistence of depression.

從生理上來說,工作不安全感引起的慢性壓力可能會過度刺激 HPA 軸和 SNS,導致皮質醇水平升高以及與憂鬱症相關的其他生理變化。認知機製表明,就業中的不安全感可能會引發負面的認知評價,例如無助感和缺乏控制感,進而可能引發憂鬱症狀。最後,行為機製表明,工作不安全感可能會引發適應不良的應對策略,例如迴避、退縮和藥物濫用,這可能會導致憂鬱症的發作和持續。

The framework also emphasizes the pivotal role of psychological safety in mediating the impact of job insecurity on employee depression. Psychological safety is delineated as an individual's perception of being able to voice their thoughts and use their abilities without fear of negative consequences. Being in a job-insecure state tends to compromise one’s sense of safety, thereby inducing psychological strain and negatively affecting employees’ authentic self-expression. This phenomenon could amplify competition among colleagues and stymie their proclivity to seek help or communicate openly, thereby exacerbating feelings of isolation and vulnerability. A significant contention of this paper is that the diminution of psychological safety consequent to job insecurity could elevate employee depression levels. This proposition, while still under-investigated, finds support in the idea that individuals experiencing low psychological safety could likely exhibit increased depression. The absence of a psychologically safe environment can induce work-related stress, anxiety, and fear, possibly triggering a spectrum of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression. Moreover, environments lacking psychological safety could inhibit help-seeking behavior, limit open communication, and increase feelings of isolation, thereby worsening depression.

該框架也強調了心理安全在調節工作不安全感對員工憂鬱的影響方面的關鍵作用。心理安全被描述為個人認為能夠表達自己的想法並運用自己的能力而不用擔心負面後果。處於工作不穩定的狀態往往會損害員工的安全感,進而引發心理壓力,並對員工真實的自我表達產生負面影響。這種現象可能會加劇同事之間的競爭,並阻礙他們尋求幫助或公開溝通的傾向,從而加劇孤立感和脆弱感。本文的一個重要論點是,工作不安全感導致的心理安全感下降可能會提高員工的憂鬱程度。這個命題雖然尚未得到充分研究,但得到了以下觀點的支持:心理安全感較低的個體可能會表現出憂鬱程度增加。缺乏心理安全的環境會引發與工作相關的壓力、焦慮和恐懼,可能引發一系列不良的心理健康結果,包括憂鬱症。此外,缺乏心理安全感的環境可能會抑制尋求協助的行為,限制開放的溝通,增加孤立感,進而加劇憂鬱症。

Moreover, the mediating role of psychological safety in the relationship between job insecurity and depression can be elucidated through an integration of established theoretical frameworks. First, stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) model (Jex, 1998) provides a framework for understanding how stressors (like job insecurity) lead to psychological strains (such as reduced psychological safety), which in turn result in negative outcomes (including depression). Job insecurity serves as an external stressor that disrupts an employee's sense of security and stability. This disruption can strain an employee’s psychological state, diminishing their sense of safety within the workplace. The reduced psychological safety, in turn, can act as a precursor to depression, thereby mediating the impact of job insecurity on depressive symptoms.

此外,可以透過整合現有的理論架構來闡明心理安全感在工作不安全感和憂鬱之間關係中的中介作用。首先,壓力源-壓力-結果(SSO)模型(Jex, 1998 )提供了一個框架,用於理解壓力源(如工作不安全感)如何導致心理壓力(如心理安全感降低),進而導致負面結果(包括憂鬱症) )。工作不安全感是一種外在壓力源,會破壞員工的安全感和穩定感。這種幹擾可能會使員工的心理狀態緊張,從而降低他們在工作場所的安全感。心理安全感的降低反過來可能成為憂鬱症的先兆,進而調節工作不安全感對憂鬱症狀的影響。

Next, conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) also posits that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect their resources. Psychological safety is a valuable resource that employees seek to maintain in their work environment. When job insecurity threatens this resource, employees may experience heightened stress and anxiety, leading to a depletion of psychological safety. This erosion of safety can render employees more susceptible to depression, positioning psychological safety as a mediator in the job insecurity-depression nexus.

其次,資源節約(COR)理論(Hobfoll, 1989 )也假設個人努力獲取、保留和保護他們的資源。心理安全是員工在工作環境中尋求維持的寶貴資源。當工作不安全感威脅到這項資源時,員工可能會承受更大的壓力和焦慮,導致心理安全感下降。這種對安全感的侵蝕會使員工更容易患上憂鬱症,將心理安全感視為工作不安全感與憂鬱症關係的中介因素。

Lastly, uncertainty management theory (Lind & Van den Bos, 2002) emphasizes how individuals respond to uncertainty. Job insecurity introduces uncertainty, leading to ambiguity in role expectations and future prospects. This uncertainty can undermine employees' psychological safety as they struggle to navigate an unpredictable work environment. The resulting decrease in psychological safety can increase the risk of depression, thus mediating the relationship between job insecurity and depression.

最後,不確定性管理理論(Lind & Van den Bos, 2002 )強調個人如何處理不確定性。工作不安全感帶來了不確定性,導致角色期望和未來前景模糊。當員工努力適應不可預測的工作環境時,這種不確定性可能會損害員工的心理安全。由此導致的心理安全感下降會增加憂鬱症的風險,進而調節工作不安全感和憂鬱症之間的關係。

By integrating the hypotheses into a comprehensive research model, the following hypothesis is proposed.

透過將假設整合到綜合研究模型中,提出以下假設。

-

Hypothesis 4: Employee psychological safety mediates the job insecurity–depression link.

假設4:員工心理安全感在工作不安全感與憂鬱之間發揮中介效果。

Moderating role of employee self-efficacy in AI use in the job insecurity–psychological safety link

員工自我效能感在工作不安全感-心理安全環節人工智慧使用中的調節作用

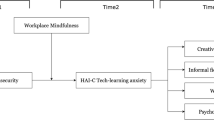

This study analyzes the moderating role of employee self-efficacy related to the use of AI in the link between job insecurity and psychological safety. Specifically, it hypothesizes that employee self-efficacy in AI usage will mitigate the harmful effects of job insecurity on psychological safety. As addressed previously, the conclusion that members who feel a sense of job insecurity may feel a low level of psychological safety would be reasonable and feasible. However, it is noteworthy that the impact of job insecurity on psychological safety can vary in different workplace contexts. This variation is due to many variables, including personal characteristics, working years, the relationships between leaders and followers, and an organization’s rules and culture, and can either positively or negatively moderate the linkage between job insecurity and psychological safety. Of these potential moderators, this paper focuses on the importance of employee self-efficacy in AI usage, drawing on Bandura’s (1982) social cognitive theory, which suggests that self-efficacy beliefs impact an individual’s behavior, motivation, and performance.

本研究分析了與人工智慧使用相關的員工自我效能感在工作不安全感和心理安全感之間的調節作用。具體來說,它假設員工在人工智慧使用中的自我效能感將減輕工作不安全感對心理安全的有害影響。如前所述,感到工作不安全感的成員可能會感到心理安全感較低,這結論是合理且可行的。然而,值得注意的是,工作不安全感對心理安全的影響在不同的工作場所環境中可能有所不同。這種差異是由許多變數造成的,包括個人特徵、工作年限、領導者和追隨者之間的關係以及組織的規則和文化,並且可以積極或消極地調節工作不安全感和心理安全感之間的聯繫。在這些潛在的調節因素中,本文借鑒班杜拉(Bandura, 1982 )的社會認知理論,重點關注員工自我效能在人工智慧使用中的重要性,該理論表明自我效能信念影響個人的行為、動機和績效。

We propose that employee self-efficacy in AI usage can mitigate the harmful effects of job insecurity on psychological safety. The moderating role of employee self-efficacy in AI use within the relationship between job insecurity and psychological safety can be theoretically anchored in several key psychological frameworks. Understanding this moderating role is crucial for comprehending how personal capabilities in AI usage can influence the impact of job insecurity on an employee's sense of psychological safety.

我們認為,人工智慧使用中的員工自我效能可以減輕工作不安全感對心理安全的有害影響。在工作不安全感和心理安全感之間的關係中,員工自我效能感在人工智慧使用中的調節作用理論上可以基於幾個關鍵的心理框架。了解這種調節作用對於理解人工智慧使用中的個人能力如何影響工作不安全感對員工心理安全感的影響至關重要。

First, self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1977) can provide a theoretical foundation for our argument. Central to this discussion is Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments. High self-efficacy in AI use suggests that employees feel confident in their ability to effectively utilize AI technologies. This confidence can serve as a buffer against the negative effects of job insecurity, mitigating its impact on psychological safety. Employees who are proficient in AI may perceive themselves as more adaptable and valuable, thereby reducing the anxiety and vulnerability associated with job insecurity (Bandura, 1997).

首先,自我效能理論(Bandura, 1977 )可以為我們的論證提供理論基礎。這次討論的核心是班杜拉的自我效能概念,它是指個人相信自己有能力執行產生特定績效成就所必需的行為。人工智慧使用的高自我效能顯示員工對自己有效利用人工智慧技術的能力充滿信心。這種信心可以緩衝工作不安全感的負面影響,並減輕其對心理安全的影響。精通人工智慧的員工可能會認為自己更具適應力和價值,從而減少與工作不安全感相關的焦慮和脆弱性(Bandura, 1997 )。

Second, technology acceptance model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) also posits that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are fundamental in determining an individual's acceptance of technology. Employee self-efficacy in AI use can enhance both these perceptions, leading to a more positive outlook toward technology in the workplace. This positive attitude can reduce the perceived threat of job insecurity related to technological advancements, thereby moderating its impact on psychological safety (Davis, 1989).

其次,技術接受模型(TAM)(Davis, 1989 )也假設感知的易用性和感知的有用性是決定個人對技術接受程度的基礎。員工在人工智慧使用中的自我效能可以增強這兩種看法,從而對工作場所的技術產生更積極的看法。這種積極的態度可以減少與技術進步相關的工作不安全感的威脅,從而減輕其對心理安全的影響(Davis, 1989 )。

Lastly, resource-based view (RBV) of the firm (Barney, 1991) bolster the argument of this paper. In the RBV framework, resources, including employee skills and capabilities, are viewed as critical to gaining a competitive advantage. High self-efficacy in AI use can be seen as a valuable resource that employees possess, which might help them feel more secure in their roles despite job insecurity. This sense of security can preserve or enhance their psychological safety within the organization (Barney, 1991).

最後,公司的基於資源的觀點(RBV)(Barney, 1991 )支持了本文的論點。在 RBV 框架中,包括員工技能和能力在內的資源被視為獲得競爭優勢的關鍵。人工智慧使用中的高自我效能感可以被視為員工擁有的寶貴資源,這可能有助於他們在工作不穩定的情況下對自己的角色感到更加安全。這種安全感可以保持或增強他們在組織內的心理安全(Barney, 1991 )。

For example, employees who feel high self-efficacy in AI usage are more likely to adopt and use new technologies effectively (Bandura, 1982). Additionally, they tend to experience a sense of competence and mastery over their tasks. In turn, this sense can increase their feelings of psychological safety because they will likely be more confident in dealing with work-related challenges and uncertainties. Such positive perceptions likely diminish the harmful effects of job insecurity on psychological safety by functioning as a buffering factor (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Bandura, 1982; Tambe et al., 2019). Based on this argument, the following hypothesis is proposed.

例如,在人工智慧使用中感到高度自我效能的員工更有可能有效地採用和使用新技術(Bandura, 1982 )。此外,他們往往會體驗到一種能力感和對任務的掌控感。反過來,這種感覺可以增加他們的心理安全感,因為他們在應對與工作相關的挑戰和不確定性時可能會更有信心。這種正向的認知可能會起到緩衝因素的作用,從而減少工作不安全感對心理安全的有害影響(Ayyagari et al., 2011 ;Bandura, 1982 ;Tambe et al., 2019 )。基於這個論點,提出以下假設。

-

Hypothesis 5: Employee self-efficacy in AI usage mitigates the harmful effects of job insecurity on psychological safety.

假設5:人工智慧使用中的員工自我效能減輕了工作不安全感對心理安全的有害影響。

Methods 方法

Participants and procedure

參與者和程序

The current research recruited participants over 20 years of age from a variety of South Korean firms and collected data during three distinct periods. The recruitment process involved hiring an online survey company with a large panelist population. Using an online survey firm is a recognized method for accessing various samples (Landers & Behrend, 2015). The study aimed to augment the limitations of cross-sectional research design by tracking identical respondents during the three time periods using the online system’s operating functions. The interval between the first and second surveys was 6 or 7 weeks. Additionally, the interval between the second and last surveys was 7 or 8 weeks. The survey system was available for 2 or 3 days during each period.

目前的研究從多家韓國公司招募了 20 歲以上的參與者,並收集了三個不同時期的數據。招聘過程涉及聘請一家擁有大量小組成員的線上調查公司。使用線上調查公司是獲取各種樣本的公認方法(Landers & Behrend, 2015 )。該研究旨在透過使用線上系統的操作功能在三個時間段內追蹤相同的受訪者來擴大橫斷面研究設計的局限性。第一次和第二次調查之間的間隔為6或7週。此外,第二次和最後一次調查之間的間隔為 7 或 8 週。每個時期調查系統的可用時間為 2 至 3 天。

To secure participant agreement, experts from the research institute personally engaged with potential respondents; thus ensuring that their participation was entirely voluntary. These experts also safeguarded participants’ privacy by guaranteeing the anonymity of their responses and their use solely for research purposes. The research institution upheld ethical norms and obtained explicit permission from respondents who willingly participated in the study. Additionally, the respondents were given a financial incentive (US$8–9) for their participation. Finally, this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of a South Korean university.

為了獲得參與者的同意,研究所的專家親自與潛在的受訪者接觸;從而確保他們的參與完全是自願的。這些專家還透過確保參與者的回答匿名且僅用於研究目的來保護參與者的隱私。研究機構恪守道德規範,並獲得自願參與研究的受訪者的明確許可。此外,受訪者的參與也獲得了經濟獎勵(8-9 美元)。最後,這項研究得到了韓國大學機構審查委員會(IRB)的批准。

To reduce participant selection bias, the research institute implemented stratified random sampling. This procedure involves procuring a random selection from each subset or stratum, which helps reduce potential skewing originating from diverse employee characteristics, such as gender, age, position, educational background, and industry type. By utilizing an online survey platform, the research team could supervise participants throughout the three stages of the survey process and confirm the continuity of respondents between the first and third time points.

為了減少參與者選擇偏差,研究所實施了分層隨機抽樣。此過程涉及從每個子集或階層中進行隨機選擇,這有助於減少源自不同員工特徵(例如性別、年齡、職位、教育背景和行業類型)的潛在偏差。透過利用線上調查平台,研究團隊可以對調查過程的三個階段的參與者進行監督,並確認受訪者在第一和第三時間點之間的連續性。

At Time Point 1, 766 employees participated in the survey, while at Time Points 2 and 3, 542 and 409 employees participated in the second and third surveys, respectively. After excluding incomplete data, complete responses were obtained from 408 participants for all three surveys, representing a response rate of 53.26%. The sample size was determined by considering various recommendations from prior research, such as determining sample size suitability using G*Power statistical analysis and ensuring a minimum sample size of 10 cases per variable as suggested by Barclay et al. (1995).

在時間點 1,有 766 名員工參與了調查,而在時間點 2 和時間點 3,分別有 542 名員工和 409 名員工參與了第二次和第三次調查。排除不完整數據後,三項調查均獲得 408 名參與者的完整答复,答复率為 53.26%。樣本量是透過考慮先前研究的各種建議來確定的,例如使用 G*Power 統計分析確定樣本量的適用性,並確保每個變數的最小樣本量為 10 個案例,如 Barclay 等人所建議的。 ( 1995 )。

Measures 措施

Three different surveys were conducted to measure various aspects of our research model. During the first survey, participants were asked about their perceptions of job insecurity and self-efficacy in using AI. The second survey measured their psychological safety, while the third collected data about their experience of depression, if any. All variables were evaluated with multi-item scales on a five-point Likert-type scale, with “1” representing strong disagreement and “5” expressing strong agreement. Each variable’s internal consistency was calculated using Cronbach's α values to ensure result reliability.

進行了三項不同的調查來衡量我們研究模型的各個方面。在第一項調查中,參與者被問及他們對工作不安全感和使用人工智慧的自我效能的看法。第二項調查測量了他們的心理安全性,而第三項調查則收集了有關他們憂鬱經歷的數據(如果有的話)。所有變項均以李克特五點量表的多項目量表進行評估,「1」表示強烈不同意,「5」表示強烈同意。使用Cronbach's α值計算每個變數的內部一致性,以確保結果的可靠性。

Job insecurity (Time Point 1, collected from members of an organization)

工作不安全感(時間點 1,從組織成員收集)

This study measured employee job insecurity by adapting five items from Kraimer et al.’s (2005) job insecurity scale. Sample items include “If my current organization was facing economic problems, my job would be the first to go,” “I will not be able to keep my present job as long as I wish,” and “My job is not a secure one.” The Cronbach’s α value was 0.89.

本研究透過改編 Kraimer 等人 ( 2005 ) 工作不安全感量表中的五個項目來衡量員工的工作不安全感。範例項目包括「如果我目前的組織面臨經濟問題,我的工作將首先消失」、「我將無法如我所願地保留目前的工作」以及「我的工作沒有保障」 」。 Cronbach's α 值為 0.89。

Self-efficacy in AI Use (Time Point 1, collected from employees)

人工智慧使用中的自我效能(時間點 1,從員工收集)

To evaluate the extent of self-efficacy in AI use, Bandura’s self-efficacy scale (Bandura, 2006) was adapted for AI use. Sample items include “I am confident in my ability to utilize artificial intelligence technology (e.g., ChatGPT) appropriately in my work when it is introduced”; “I am able to utilize artificial intelligence technology (e.g., ChatGPT) to perform my job well, even when the situation is challenging”; and “I can utilize artificial intelligence technology (e.g., ChatGPT) to successfully accomplish my goals in the course of my work.” The Cronbach’s α value was 0.94.

為了評估人工智慧使用中的自我效能程度,班杜拉的自我效能感量表(Bandura, 2006 )適用於人工智慧的使用。範例項目包括「當引入人工智慧技術(例如 ChatGPT)時,我對自己在工作中適當利用它的能力充滿信心」; 「即使情況充滿挑戰,我也能夠利用人工智慧技術(例如 ChatGPT)來出色地完成我的工作」; “我可以利用人工智慧技術(例如ChatGPT)在工作過程中成功實現我的目標。” Cronbach's α 值為 0.94。

Psychological safety (Time Point 2, collected from employees)

心理安全(時間點2,從員工收集)

The extent of employee psychological safety was assessed using a four-item scale developed by Edmondson (1999). This scale aimed to gauge employee perceptions of psychological safety in the workplace. Sample items included “It is safe to take a risk in this organization,” “I am able to bring up problems and tough issues in this organization,” “It is easy for me to ask other members of this organization for help,” and “No one in this organization would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts.” Researchers have used these items in other studies with South Korean employees (e.g., Kim et al., 2021). The Cronbach’s α value was 0.83.

員工心理安全程度採用 Edmondson( 1999 )所發展的四項量表進行評估。此量表旨在衡量員工對工作場所心理安全的看法。範例項目包括“在這個組織中冒險是安全的”、“我能夠在這個組織中提出問題和棘手的問題”、“我很容易向這個組織的其他成員尋求幫助”,以及“這個組織中沒有人會故意採取破壞我努力的方式。研究人員在其他針對韓國員工的研究中使用了這些物品(例如 Kim 等人, 2021 )。 Cronbach's α 值為 0.83。

Depression (Time Point 3, collected from employees)

憂鬱症(時間點 3,從員工收集)

To assess the level of depression among participants, the CES-D-10 was utilized, which includes 10 items developed by Andresen et al. (1994). This scale measures various aspects of depression, including, but not limited to, feelings of hopelessness, fear, loneliness, unhappiness, and difficulties with attention and sleep. Sample items included “I felt hopeful about the future,” “I felt lonely,” “I could not get going,” and “I felt depressed.” The Cronbach’s α value was 0.96.

為了評估參與者的憂鬱程度,使用了 CES-D-10,其中包括 Andresen 等人開發的 10 個項目。 ( 1994 )。此量表衡量憂鬱症的各個方面,包括但不限於絕望感、恐懼感、孤獨感、不快樂感以及注意力和睡眠困難。範例項目包括「我對未來感到充滿希望」、「我感到孤獨」、「我無法前進」和「我感到沮喪」。 Cronbach's α 值為 0.96。

Control variables 控制變數

Drawing on previous research (Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016; Jacobson & Newman, 2017; Lerner & Henke, 2008), several control variables were included in our analysis to account for the potential influence of factors including employee tenure, gender, position, and education. Control variable data were collected during the first survey. According to the literature, the inclusion of control variables, such as tenure, gender, education, and position in our analysis can be prudent because these variables are often linked to psychological safety, job insecurity, and depression. These control variables are typically chosen because they may reduce omitted variable bias while also allowing for a clearer interpretation of the primary variables of interest.

根據先前的研究(Evans–Lacko & Knapp, 2016 ;Jacobson & Newman, 2017 ;Lerner & Henke, 2008 ),我們的分析中納入了幾個控制變量,以解釋員工任期、性別、職位、和教育。控制變數資料是在第一次調查期間收集的。根據文獻,在我們的分析中納入控制變量,如任期、性別、教育和職位是謹慎的,因為這些變量通常與心理安全、工作不安全感和憂鬱有關。通常選擇這些控制變數是因為它們可以減少遺漏變數偏差,同時還可以更清晰地解釋感興趣的主要變數。

Tenure, for example, is generally included as a control variable in organizational studies because length of service may influence an individual’s perception of job security and psychological well-being. Gender is another common control variable, given well-documented gender-based differences in mental health outcomes. Additionally, education and position may affect an individual’s self-efficacy in AI use, their perceived job insecurity, and their susceptibility to depression.

例如,任期通常被作為組織研究中的控制變量,因為服務年資可能會影響個人對工作保障和心理健康的看法。鑑於心理健康結果中基於性別的差異有據可查,性別是另一個常見的控制變數。此外,教育和職位可能會影響個人在人工智慧使用方面的自我效能、他們感知到的工作不安全感以及他們對憂鬱症的易感性。

However, the lack of statistical significance among these control variables in the analysis requires further consideration. The results indicate that these factors may not be major contributors to job insecurity, psychological safety, and depression in this specific context. The insignificance may have originated for various reasons. For example, it is possible that the impact of the control variables was overshadowed by other, more influential factors not included in our model. Alternatively, the nature of the dataset, or the characteristics of the specific population sampled, could mean that these variables were simply not as salient in this particular context. Further exploration of why these control variables were not significant in the present study could offer valuable insights.

然而,分析中這些控制變數之間缺乏統計顯著性,需要進一步考慮。結果表明,在這種特定情況下,這些因素可能不是導致工作不安全感、心理安全感和憂鬱症的主要因素。這種微不足道的現象可能是由多種原因造成的。例如,控制變數的影響可能被我們模型中未包含的其他更具影響力的因素所掩蓋。或者,資料集的性質或採樣的特定人群的特徵可能意味著這些變數在這個特定背景下並不那麼顯著。進一步探討為什麼這些控制變數在本研究中並不重要,可以提供有價值的見解。

Statistical analysis 統計分析

A frequency analysis was conducted to examine participants’ demographic characteristics. Next, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationships among the study variables. The study utilized the two-step approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), which involved first testing the measurement model and then testing the structural model. Additionally, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to assess the validity of the measurement model. Finally, a moderated mediation model analysis was conducted using AMOS 26 with the maximum likelihood estimator to test the structural model based on SEM.

進行頻率分析以檢查參與者的人口統計特徵。接下來,進行皮爾遜相關分析來探討研究變項之間的關係。研究採用了Anderson和Gerbing( 1988 )推薦的兩步驟方法,首先測試測量模型,然後測試結構模型。此外,還進行了驗證性因素分析(CFA)以評估測量模型的有效性。最後,使用AMOS 26和最大似然估計器進行有調節的中介模型分析,以測試基於SEM的結構模型。

This study utilized various goodness-of-fit indices, including the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) to test whether the model fit was acceptable. Previous studies have suggested that values greater than 0.90 for CFI and TLI and less than 0.06 for RMSEA are appropriate (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Additionally, a bootstrap analysis was conducted to assess whether the indirect effect was significant with a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI), which is used to assess the significance of the mediation effect. If the CI does not include zero (0), it suggests that the indirect effect is statistically significant at a 0.05 level (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

本研究利用各種配適優度指數,包括比較適配指數(CFI)、Tucker-Lewis指數(TLI)和近似均方根誤差(RMSEA)來測試模型適配是否可接受。先前的研究表明,CFI 和 TLI 的值大於 0.90,RMSEA 的值小於 0.06 是適當的(Browne & Cudeck, 1993 )。此外,還進行了引導分析,以評估間接效應是否具有 95% 偏倚校正置信區間 (CI) 顯著性,該區間用於評估中介效應的顯著性。如果 CI 不包括零 (0),則表示間接效應在 0.05 水準上具有統計顯著性(Shrout & Bolger, 2002 )。

Results 結果

Descriptive statistics 描述性統計

The research variables (job insecurity, self-efficacy in AI use, psychological safety, and depression) were significantly associated. Table 1 describes the correlation results.

研究變項(工作不安全感、人工智慧使用的自我效能感、心理安全感和憂鬱症)有顯著相關。表1描述了相關結果。

表1 研究變項之間的相關性

Measurement model 測量模型

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed for all items to confirm the goodness-of-fit of the measurement model and to assess the discriminant validity of the main research variables. The hypothesized four-factor model (job insecurity, self-efficacy in AI use, psychological safety, and depression) was compared to alternative models, including three-, two-, and one-factor models through a series of chi-square difference tests. Results indicated that the hypothesized four-factor model had a good and acceptable fit (χ2 (df = 128) = 202.805, CFI = 0.986, TLI = 0.983, RMSEA = 0.038) compared to the three-factor model (χ2 (df = 131) = 1979.157, CFI = 0.649, TLI = 0.590, RMSEA = 0.186). The four-factor model was also better than both the two-factor model (χ2 (df = 133) = 2492.164, CFI = 0.551, TLI = 0.484, RMSEA = 0.209) and one-factor model (χ2 (df = 134) = 3303.400, CFI = 0.397, TLI = 0.312, RMSEA = 0.241), as indicated by various goodness-of-fit indices. Furthermore, the four-factor model was found to be significantly better than alternative models, suggesting that the four research variables possess appropriate discriminant validity.

對所有題項進行驗證性因素分析(CFA),以確認測量模型的適配優度並評估主要研究變項的區分效度。透過一系列卡方差異檢驗,將假設的四因素模型(工作不安全感、人工智慧使用中的自我效能感、心理安全感和憂鬱症)與其他模型(包括三因素、二因素和單因素模型)進行比較。結果表明,與三因素模型(χ 2 ( df = 128) = 202.805、CFI = 0.986、TLI = 0.983、RMSEA = 0.038)相比,假設的四因素模型具有良好且可接受的適配度(χ 2 ( df = 128) = 202.805)。四因素模型也優於二因素模型(χ 2 ( df = 133) = 2492.164,CFI = 0.551,TLI = 0.484,RMSEA = 0.209)和一因子模型(χ 2 ( df = 134) ) = 3303. 0.397,TLI = 0.312,RMSEA = 0.241),如各種配適優度指標所示。此外,發現四因素模型明顯優於其他模型,顯示四個研究變項具有適當的區分效度。

Structural model 結構模型

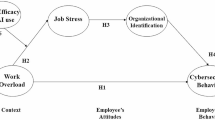

In this study, a model that considered mediation and moderation structures in the relationship between job insecurity and depression was created. In the mediation structure, the employees’ degree of psychological safety mediated the effect of job insecurity on depression. Meanwhile, in the moderation structure, the role of self-efficacy in AI use was explored as a protective factor that buffers the negative impact of job insecurity on psychological safety. To accomplish this, an interaction term was created between the two variables by centering them on their means to reduce the adverse effects of multicollinearity. This method improved the accuracy of the moderation analysis by minimizing the loss of correlations and reducing the degree of multicollinearity among the variables (Brace et al., 2003).

在這項研究中,創建了一個考慮工作不安全感和憂鬱之間關係的中介和調節結構的模型。在中介結構中,員工的心理安全度在工作不安全感對憂鬱的影響中扮演中介角色。同時,在調節結構中,自我效能在人工智慧使用中的作用被探討作為緩衝工作不安全感對心理安全的負面影響的保護因子。為了實現這一目標,透過將兩個變數集中在它們的平均值上,在兩個變數之間創建了一個交互項,以減少多重共線性的不利影響。此方法透過最大限度地減少相關性損失並降低變數之間的多重共線性程度,提高了調節分析的準確性(Brace et al., 2003 )。

Furthermore, to assess the impact of multicollinearity bias, the variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerances (Brace et al., 2003) were calculated with the VIF values for job insecurity and self-efficacy in AI use found to be 1.005 and 1.005, respectively. Additionally, the tolerance values for these variables were 0.995 and 0.995, respectively. Because the VIF values were below 10 and the tolerance values were above 0.2, we concluded that multicollinearity did not significantly affect job insecurity and self-efficacy in AI use (Fig. 1).

此外,為了評估多重共線性偏差的影響,計算了方差膨脹因子(VIF)和容差(Brace et al., 2003 ),其中人工智慧使用中工作不安全感和自我效能感的VIF 值分別為1.005和1.005,分別。此外,這些變數的公差值分別為 0.995 和 0.995。由於VIF值低於10且公差值高於0.2,我們得出結論,多重共線性不會顯著影響人工智慧使用中的工作不安全感和自我效能(圖1 )。

Mediation analysis results

中介分析結果

To identify the optimal mediation model, a chi-square difference test was conducted to compare the fit of a full mediation model with a partial mediation model. The former included all the paths in the latter, except for the direct effect from job insecurity to depression. The full mediation model (χ2 = 234.828 (df = 139), CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.969, and RMSEA = 0.041) and the partial mediation model (χ2 = 229.613 (df = 138), CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.970, and RMSEA = 0.040) yielded acceptable fit indices. Nevertheless, the chi-square difference test (Δχ2 [1] = 5.252, p < 0.05) favored the partial mediation model, indicating that job insecurity may have an indirect influence on depression (i.e., via the mediating role of psychological safety), instead of a direct effect.

為了確定最佳中介模型,進行了卡方差異檢定來比較完全中介模型與部分中介模型的適合程度。前者包含了後者的所有路徑,除了工作不穩定對憂鬱症的直接影響之外。完全中介模型 (χ 2 = 234.828 ( df = 139)、CFI = 0.974、TLI = 0.969 和 RMSEA = 0.041) 和部分中介模型 (χ 2 = 229.613 ( df = 138) 和部分中介模型 (χ 2 = 229.613 ( df = 138)、CFI = 0.970. = 0.040)產生了可接受的適配指數。儘管如此,卡方差異檢定(Δχ 2 [1] = 5.252, p < 0.05)有利於部分中介模型,顯示工作不安全感可能對憂鬱產生間接影響(即透過心理安全的中介作用),而非直接的影響。

This study also included control variables, such as tenure, gender, education, and position, to account for their effects on safety behavior. However, the results indicated that none of these control variables were statistically significant and when these control variables were included in the research model, a significant association was found between job insecurity and employee depression (β = 0.13, p < 0.05), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. In the partial mediation model, which was superior to the full mediation model, the coefficient value of the path from job insecurity to employee depression was consistent with the model fit indices of partial mediation being superior to those of full mediation. Conducting the chi-square difference test, and considering the significance of the path, this paper assessed support for Hypothesis 1, suggesting that job insecurity is likely to have both direct and indirect effects on employee depression through various mediators, such as psychological safety.

這項研究還包括控制變量,如任期、性別、教育和職位,以解釋它們對安全行為的影響。然而,結果表明,這些控制變量均不具有統計顯著性,並且當將這些控制變量納入研究模型時,發現工作不安全感與員工憂鬱之間存在顯著關聯(β = 0.13, p < 0.05) ,從而支持假設1.在優於完全中介模型的部分中介模型中,從工作不安全感到員工抑鬱的路徑係數值與部分中介優於完全中介的模型擬合指數一致。透過卡方差異檢驗,並考慮路徑的顯著性,本文評估了對假設1的支持,顯示工作不安全感可能透過各種中介因素(例如心理安全感)對員工憂鬱產生直接和間接影響。

To account for potential confounding variables, our research model included tenure, gender, education, and position as control variables. However, the results indicated that none of the control variables were statistically significant. The research model, which included the control variables, demonstrated that job insecurity had a significant positive association with employee depression (β = 0.13, p < 0.05), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. This finding was consistent with the model fit indices of the partial mediation model being superior to those of the full mediation model. Additionally, relying on the path coefficient’s significant value and the results of the chi-square difference test between the full and partial mediation models, this study concluded that Hypothesis 1 was supported. These findings suggest that job insecurity can directly and indirectly influence employee depression through various mediators, such as psychological safety.

為了解釋潛在的混雜變量,我們的研究模型將任期、性別、教育和職位作為控制變量。然而,結果表明,所有控制變數均不具有統計顯著性。包含控制變數的研究模型表明,工作不安全感與員工憂鬱呈顯著正相關(β = 0.13, p < 0.05),從而支持假設 1。完全中介模型。此外,根據路徑係數的顯著性值以及完全中介模型和部分中介模型之間的卡方差異檢定結果,本研究得出假設1得到支持的結論。這些發現表明,工作不安全感可以透過各種中介因素(例如心理安全感)直接或間接影響員工憂鬱。

Additionally, the results indicate that job insecurity is significantly and inversely related to psychological safety (β = -0.27, p < 0.001), which supports Hypothesis 2. Moreover, psychological safety is significantly and negatively related to depression (β = -0.17, p < 0.01), which supports Hypothesis 3. The statistical finding details are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

此外,結果表明,工作不安全感與心理安全感有顯著負相關(β = -0.27, p < 0.001),這支持了假設2。 , p < 0.001 )。

表2 結構模型結果

Bootstrapping 自舉

To test Hypothesis 4, which proposes that psychological safety mediates the relationship between job insecurity and depression, a bootstrapping analysis was conducted with a sample size of 10,000 (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). The significance of the indirect mediation effect was determined by examining the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) for the mean indirect mediation effect. The result was a statistically significant indirect mediation effect at the 5% level, given that the bias-corrected CI for the mean indirect effect did not include 0 (95% CI = [0.007, 0.096]). This supports Hypothesis 4. The direct, indirect, and total effects of the paths from job insecurity to depression are shown in Table 3.

為了檢驗假設 4(提出心理安全感介導工作不安全感和憂鬱之間的關係),我們對 10,000 個樣本進行了引導分析(Shrout & Bolger, 2002 )。間接中介效應的顯著性是透過檢查平均間接中介效應的 95% 偏倚校正信賴區間 (CI) 來確定的。鑑於平均間接效應的偏倚校正 CI 不包括 0 (95% CI = [0.007, 0.096]),結果是 5% 水準上具有統計顯著性的間接中介效應。這支持了假設4 。

表3 最終研究模型的直接效果、間接效果與總效應

Moderation analysis results

調節分析結果

In the present study, the moderating effect of self-efficacy in AI use on the association between job insecurity and psychological safety was examined, and an interaction term was created by performing a mean-centering procedure. The result revealed a statistically significant coefficient value of the interaction term (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), indicating that self-efficacy in AI use was a positive moderator in the job insecurity–psychological safety link because it serves as a buffer. Thus, when an employee’s self-efficacy in AI usage was high, job insecurity had a reduced harmful influence on psychological safety. Therefore, these findings support Hypothesis 5 (see Fig. 3).