Modern digital tools make it easy to “capture” information from a wide variety of sources. We know how to snap a picture, type out some notes, record a video, or scan a document. Getting this content from the outside world into the digital world is trivial.

现代数字工具使得从各种来源“捕捉”信息变得轻而易举。我们知道如何拍照、打字记录笔记、录制视频或扫描文档。将这些内容从现实世界转移到数字世界是轻而易举的。

It’s even easier to get content that is already digital from one app to another. We know how to copy and paste text, save an image from a webpage, archive an email attachment, or import a video file.

将已经数字化的内容从一个应用程序转移到另一个应用程序甚至更加容易。我们知道如何复制和粘贴文本、从网页保存图片、归档电子邮件附件或导入视频文件。

What is difficult is not transferring content from place to place, but transferring it through time.

困难之处不在于将内容从一个地方转移到另一个地方,而在于跨越时间的传递。

You know what I mean: you read a book, investing hours of mental labor in understanding the ideas it presents. You finish the book with a feeling of triumph that you’ve gained a valuable body of knowledge.

你知道我的意思:你读了一本书,投入数小时的脑力劳动去理解它提出的观点。读完这本书时,你会有一种胜利感,觉得自己获得了宝贵的知识体系。

But then what? 但接下来呢?

You may try to apply the science-based methods the book recommends, only to realize it’s not quite as clear-cut as you thought. You may try to change the way you eat, exercise, communicate, or work, trusting in the power of habits. But then the everyday demands of life come rushing back, and you forget what motivated you in the first place.

你可能会尝试应用书中推荐的基于科学的方法,结果却发现事情并不像你想象的那么简单。你可能会尝试改变你的饮食、锻炼、交流或工作方式,相信习惯的力量。但随后,日常生活的需求又汹涌而至,你忘记了最初激励你的动力。

At this point, people take different paths. Some give up, labeling all “self-help” books a waste of time. Others decide it’s just a problem of remembering everything they read, and invest in fancy memorization techniques. And many people become “infovores,” force-feeding themselves endless books, articles, and courses, in the hope that something will stick.

此时,人们走上了不同的道路。有些人选择放弃,认为所有“自助”类书籍都是浪费时间。另一些人则认为问题在于如何记住所读内容,于是投入精力学习复杂的记忆技巧。还有许多人变成了“信息狂”,强迫自己阅读无尽的书籍、文章和课程,希望其中某些内容能够留下深刻印象。

I want to suggest an alternative to all the approaches above: what you read is good and useful and very important, you’re just reading it at the wrong time.

我想提出一个替代上述所有方法的建议:你读到的内容很好、很有用、也非常重要,只是你在错误的时间阅读了它。

You’re reading about time management techniques now, but they will only be useful two years from now, when you become a manager and have much greater demands on your time.

你现在正在阅读关于时间管理技巧的内容,但它们只有在两年后你成为经理并对时间有更高要求时才会派上用场。

You’re watching YouTube videos on online marketing now, but that knowledge can only be put to use in 9 months, when your new online course gets off the ground.

你现在正在观看关于网络营销的 YouTube 视频,但这些知识只能在 9 个月后你的新在线课程启动时派上用场。

You’re talking to a prospect about his goals and challenges now, but when you could really use that information is next year, when he is taking bids for a huge new contract.

你现在正在与一位潜在客户讨论他的目标和挑战,但真正需要这些信息的时候是明年,当他为一个巨大的新合同招标时。

The challenge of knowledge is not acquiring it. In our digital world, you can acquire almost any knowledge at almost any time.

知识的挑战不在于获取它。在我们的数字世界中,你几乎可以在任何时候获取几乎任何知识。

The challenge is knowing which knowledge is worth acquiring. And then building a system to forward bits of it through time, to the future situation or problem or challenge where it is most applicable, and most needed.

挑战在于知道哪些知识值得获取。然后构建一个系统,将这些知识的片段通过时间传递到未来最适用、最需要它们的情境、问题或挑战中。

At that future point, when you’re applying that knowledge directly to a real-world challenge, you won’t have to worry about memorizing it, integrating it, or even fully understanding it. You will only have to apply it, and any gaps in your understanding will very quickly reveal themselves. By the time you’re done solving a real problem with it, book knowledge has become experiential knowledge. And experiential knowledge is something you carry with you forever.

在未来的某个时刻,当你将所学知识直接应用于现实世界的挑战时,你无需担心记忆、整合或完全理解它。你只需应用它,而理解上的任何空白都会迅速显现。当你用它解决实际问题时,书本知识已转化为经验知识。而经验知识,是你永远随身携带的财富。

This is the job of a “second brain” — an external, integrated digital repository for the things you learn and the resources from which they come. It is a storage and retrieval system, packaging bits of knowledge into discrete packets that can be forwarded to various points in time to be reviewed, utilized, or deleted.

这是“第二大脑”的工作——一个外部的、集成的数字知识库,用于存储你所学的内容及其来源资源。它是一个存储与检索系统,将知识片段打包成独立的单元,能够被传送到不同的时间点进行复习、利用或删除。

In The PARA Method, I described a universal system for organizing any kind of digital information from any source. It is a “good enough” system, maintaining notes according to their actionability (which takes just a moment to determine), instead of their meaning (which is ambiguous and depends on the context).

在《PARA 方法》中,我描述了一种通用系统,用于组织来自任何来源的任何类型的数字信息。这是一个“足够好”的系统,根据信息的可操作性(只需片刻即可确定)而非其意义(意义模糊且依赖于上下文)来维护笔记。

The four top-level categories of PARA — Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archives — are designed to facilitate this process of forwarding knowledge through time.

PARA 的四个顶级类别——项目(Projects)、领域(Areas)、资源(Resources)和档案(Archives)——旨在促进知识随时间推移的传递过程。

- By placing a note in a project folder, you are essentially scheduling it for review on the short time horizon of an individual project

通过在项目文件夹中放置一个笔记,您实际上是在为单个项目的短期时间范围内安排审查 - Notes in area folders are scheduled for less frequent review, whenever you evaluate that area of your work or life

区域文件夹中的笔记计划进行较少频率的审查,每当您评估工作或生活的该领域时 - Notes in resource folders stand ready for review if and when you decide to take action on that topic

资源文件夹中的笔记已准备好供您审阅,以便在您决定对该主题采取行动时使用 - And notes in archive folders are in “cold storage,” available if needed but not scheduled for review at any particular time

存档文件夹中的笔记处于“冷存储”状态,需要时可用,但未安排在特定时间进行审查

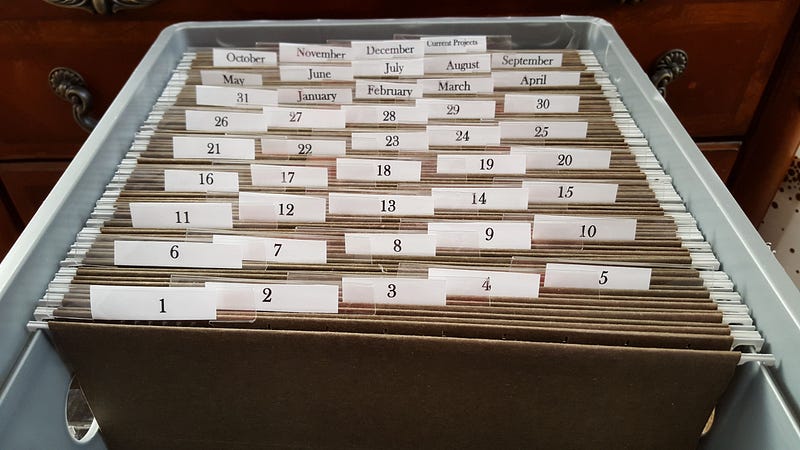

Note that we have re-created the tickler file, except instead of strict time-based horizons (daily, weekly, monthly, annually), they are scheduled contingently — if X happens, when Y arrives, if I want to do Z, etc.

请注意,我们已经重新创建了提醒文件,只不过这次不是基于严格的时间范围(每日、每周、每月、每年),而是根据条件安排——如果 X 发生,当 Y 到来时,如果我想做 Z,等等。

Planning in terms of contingencies gives us all the benefits of planning and researching, without locking us into rigid routines. We have the ability to massively accelerate, using our repository of accumulated notes as rocket fuel. But the actual decision of whether or not to accelerate, and critically, in which direction, we leave to our Future Self, who is older and wiser.

以应急情况为基础的规划让我们享有规划和研究的所有好处,而不会被僵化的常规所束缚。我们拥有大幅加速的能力,利用积累的笔记作为火箭燃料。但实际是否加速,以及关键的是,朝哪个方向加速,我们留给未来的自己决定,他们更年长、更明智。

PARA answers how these “packets of knowledge” are organized: in discrete notes, sorted into 4 categories according to actionability, and resurfaced using RandomNote.

PARA 解答了这些“知识包”是如何组织的:以离散笔记的形式,根据可操作性分为 4 类,并通过 RandomNote 重新呈现。

But now we turn to a more fundamental question: how are these packets made? Once we capture something, how do we structure the note so that it’s easily discoverable and usable in the future? How do we make sure what we’re saving today adds value to future projects, even when we can’t predict or even imagine what those projects might be?

但现在我们转向一个更基本的问题:这些信息包是如何制作的?一旦我们捕捉到某些内容,我们如何构建笔记,以便将来易于发现和使用?我们如何确保我们今天保存的内容能为未来的项目增添价值,即使我们无法预测甚至想象那些项目可能是什么?

That is the job of Progressive Summarization.

这就是渐进式总结的工作。

Note-first knowledge management

注:第一知识管理

There are two primary schools of thought on how to organize a note-taking program (or really any body of information, but I’ll use terms specific to note-taking apps):

关于如何组织笔记程序(或实际上任何信息体,但我会使用笔记应用特定的术语),主要有两种思想流派:

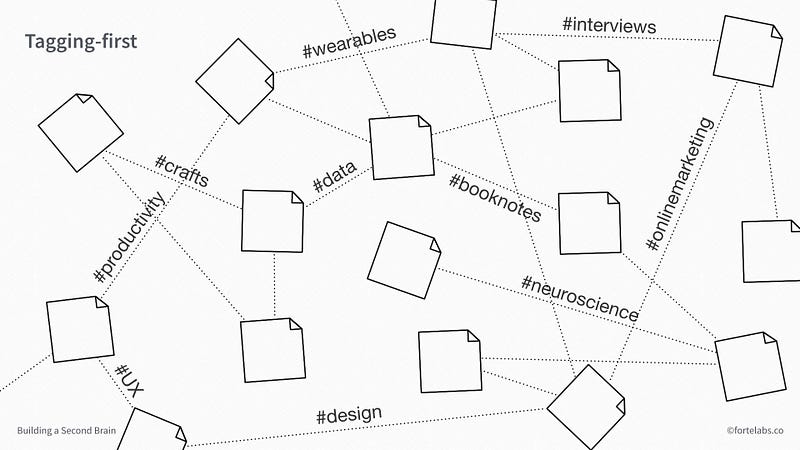

Tagging-first approaches argue that there should be no explicit hierarchy of notes, notebooks, and stacks. Notes are envisioned as an ever-changing, virtual matrix of interconnected, free-floating ideas. Because many tags can be applied to one note, there are multiple pathways to discover any given note. Locating notes in specific notebooks and folders is seen as limiting and static.

标签优先方法主张不应有笔记、笔记本和堆栈的明确层级结构。笔记被设想为一个不断变化的、虚拟的、相互连接的自由浮动想法矩阵。由于一个笔记可以应用多个标签,因此有多种途径可以发现任何给定的笔记。将笔记定位在特定的笔记本和文件夹中则被视为限制性和静态的。

Although tags have their uses, I don’t believe they work as a primary organizational system. In my experience, relying on tagging is too fragile and requires too much maintenance, spreading attention too uniformly across all notes whether or not they are truly valuable. The virtual matrix sounds cool and futuristic, but our minds are not made to work well with such abstract concepts — we understand placing one thing in one place intuitively and automatically.

尽管标签有其用途,但我不认为它们能作为主要的组织系统。根据我的经验,依赖标签过于脆弱且需要大量维护,注意力过于均匀地分散在所有笔记上,无论它们是否真正有价值。虚拟矩阵听起来很酷且未来感十足,但我们的大脑并不擅长处理如此抽象的概念——我们本能且自动地理解将某物放在一个地方。

The second conventional approach to organizing notes is notebook-first. This basically translates how we organize things in the physical world — in a series of discrete containers — into the digital world.

第二种传统的笔记组织方法是笔记本优先。这基本上将我们在物理世界中的组织方式——通过一系列离散的容器——转换到数字世界中。

Notebook-first is better than tagging-first, in my opinion, mostly because it stays out of the way. It doesn’t try to automate and encroach upon the deeply intuitive act of making connections and seeing patterns. PARA on its own is a notebook-first system.

在我看来,笔记本优先优于标签优先,主要是因为它不会干扰。它不会试图自动化并侵入建立联系和发现模式这一深度直观的行为。PARA 本身就是一个笔记本优先的系统。

But if we stopped there, it would still be woefully inadequate for an economy based on creative output. As the tagging enthusiasts correctly point out, notebooks and folders actually suppress the serendipity and randomness that is at the heart of a creative lifestyle.

但如果我们止步于此,对于以创意产出为基础的经济来说,这仍然远远不够。正如标签爱好者们正确指出的那样,笔记本和文件夹实际上抑制了偶然性和随机性,而这正是创意生活方式的核心所在。

I propose a way to break the impasse: a note-first approach.

我提出一种打破僵局的方法:以笔记为先的方法。

I propose we make the design of individual notes the primary factor, instead of tags or notebooks. This has many advantages:

我建议我们将单个笔记的设计作为主要因素,而不是标签或笔记本。这有许多优势:

- It works well with any other organizational system, without depending on them (including but not limited to tags and notebooks, if you want to use those)

它与任何其他组织系统都能很好地配合,而不依赖于它们(包括但不限于标签和笔记本,如果你想使用这些的话) - It makes all work you do on your notes value-added, because you’re spending close to 100% of the time engaging directly with the content itself

它使你在笔记上所做的所有工作都增值,因为你几乎 100%的时间都在直接与内容本身互动 - It can more easily survive migrations to other devices, storage locations, and even programs, because note content is much more likely to be preserved than overarching structure

它可以更容易地在迁移到其他设备、存储位置甚至程序时存活下来,因为笔记内容比整体结构更有可能被保留 - It cultivates skills (succinct communication, finding the core of an idea, visual thinking, etc.) that are inherently valuable and highly transferrable to other activities

它培养的技能(简洁沟通、抓住思想核心、视觉思维等)本身具有价值,并且高度可转移到其他活动中。 - It makes your notes more legible and useful to others (unlike your internal notebook structure, which is only for your use), promoting collaboration and sharing

它使您的笔记对他人来说更易读且更有用(与仅供您使用的内部笔记本结构不同),促进了协作和共享

With a note-first approach, your notes become like individual atoms — each with its own unique properties, but ready to be assembled into elements, molecules, and compounds that are far more powerful.

采用笔记优先的方法,您的笔记就像一个个独立的原子——每个都有其独特的属性,但随时可以组合成更强大的元素、分子和化合物。

Designing discoverable notes

设计可发现的笔记

A note-first approach to knowledge management means we have to think about design. You are, in a very real sense, designing a product for a demanding customer — Future You.

以笔记为先的知识管理方法意味着我们必须考虑设计。在非常真实的意义上,你正在为一个苛刻的客户——未来的你——设计一个产品。

Future You doesn’t necessarily trust that everything Past You put into your notes is valuable. Future You is impatient and skeptical, demanding proof upfront that the time they spend reviewing notes will be worthwhile. You’ve gotta “sell them” on the idea of reviewing a given note, including all the stages any salesperson has to master: gaining attention, inspiring interest, establishing credibility, stoking desire, and making a case for action NOW.

未来的你并不一定相信过去的你在笔记中记录的所有内容都是有价值的。未来的你缺乏耐心且持怀疑态度,要求提前证明他们花时间复习笔记是值得的。你必须“向他们推销”复习某条笔记的想法,包括任何销售人员都必须掌握的所有阶段:引起注意、激发兴趣、建立可信度、激发欲望,并立即提出行动的理由。

As if all that wasn’t intimidating enough, you have to do this for every single note without spending any extra time. You don’t have extra time, do you?

仿佛这一切还不够令人生畏,你必须在没有任何额外时间的情况下为每一个音符做到这一点。你没有额外的时间,对吧?

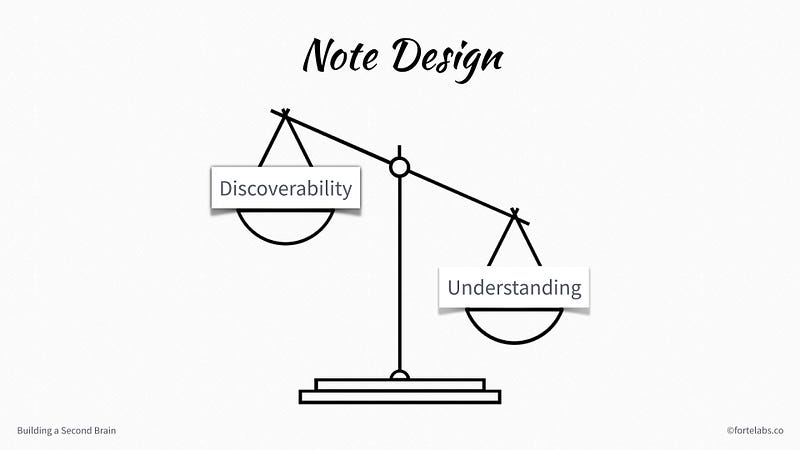

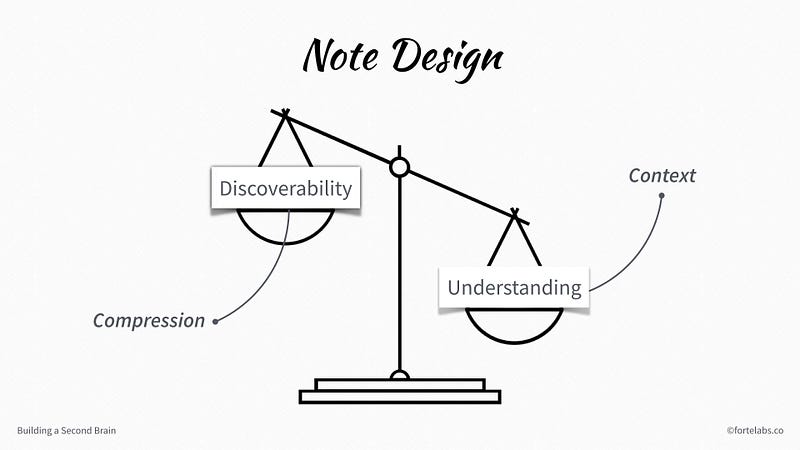

Let’s start at the beginning: at the heart of every design, we are trying to balance priorities. You want one thing, but it has to be balanced against something else that you also want.

让我们从头开始:在每个设计的核心,我们都在努力平衡优先级。你想要一件事,但它必须与你同样想要的其他事情相平衡。

You want a vehicle to protect its occupants, but you can’t just add layers and layers of titanium armor plating. You have to balance safety against weight and cost.

你想要一辆能保护乘员的车辆,但不能简单地一层又一层地添加钛合金装甲板。你必须在安全性、重量和成本之间找到平衡。

You want a phone to have the longest possible battery life, but you can’t just give it a 10-pound brick of a battery. You have to balance battery life against size and usability.

你想要手机拥有尽可能长的电池续航,但不能仅仅给它装上 10 磅重的电池块。你必须在电池续航与尺寸及可用性之间找到平衡。

In the case of notes, I believe the two priorities we are trying to balance are discoverability and understanding.

在笔记方面,我认为我们试图平衡的两个重点是可发现性和理解性。

Making a note discoverable involves making it small, simple, and easy to digest. We accomplish this using compression: creating highly condensed summaries, without all the fluff.

使笔记易于发现需要使其简短、简洁且易于消化。我们通过压缩来实现这一点:创建高度浓缩的摘要,去除所有冗余内容。

But we also want to make our notes understandable. This involves including all the context: the details, the examples, and cited sources to be sure nothing falls through the cracks.

但我们也希望让我们的笔记易于理解。这包括包含所有上下文:细节、例子和引用的来源,以确保没有任何遗漏。

This is a difficult tradeoff because you cannot compress something without losing some of its context.

这是一个艰难的权衡,因为你无法在不丢失部分上下文的情况下压缩某些内容。

You cannot summarize an article without discarding most of its points. You cannot make a highlight reel of a video without cutting out most of the footage. You cannot give an 18-minute TED talk without leaving out most of your ideas.

你无法在不舍弃大部分要点的情况下总结一篇文章。你无法在不剪掉大部分镜头的情况下制作视频精彩片段。你无法在不省略大部分想法的情况下进行 18 分钟的 TED 演讲。

In making decisions about what to keep, you are inevitably making decisions about what to throw away.

在决定保留什么时,你不可避免地也在决定丢弃什么。

Compression vs. context

There’s a natural tension between the two, compression and context.

To communicate anything, you have to compress it, like communicating a huge amount of life experience in a wise saying. But in doing so, you lose a lot of the context that made that wisdom valuable in the first place.

Let’s look at some examples.

让我们看一些例子。

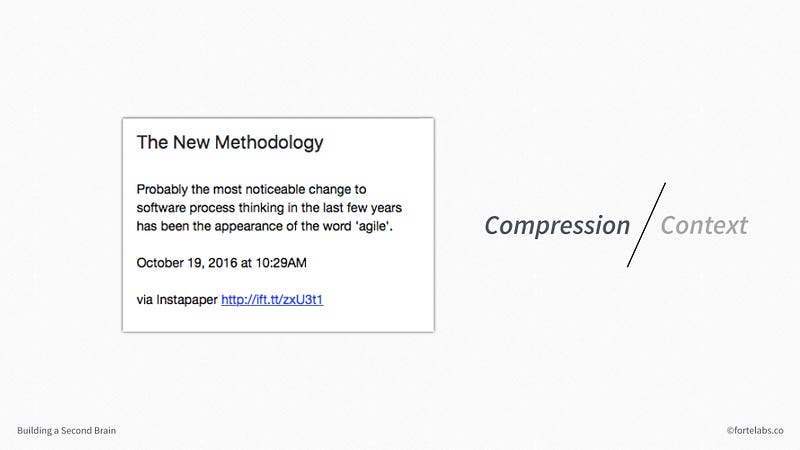

If we compress a note too much, in other words, we make a summary that is too brief, we lose the context and it loses all meaning. In the note above, for example, the information it contains is highly discoverable — I can get the gist of it with just a glance.

如果我们把笔记压缩得太多,换句话说,我们做的摘要过于简短,就会失去上下文,从而失去所有意义。例如,在上面的笔记中,它所包含的信息非常容易被发现——我只需一眼就能抓住要点。

But if I come across this note a year from now, I’ll have no idea what it means or why it’s important. It’s too compressed.

但如果我一年后看到这条笔记,我会完全不明白它的意思或为什么重要。它太简略了。

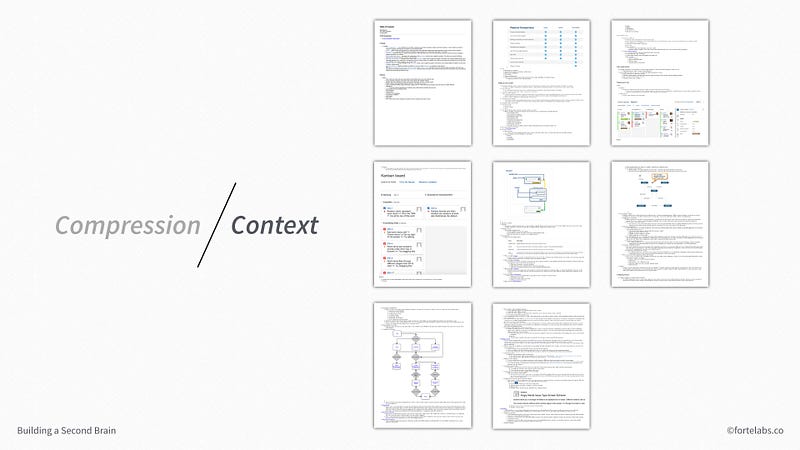

But we can go too far in the opposite direction too. If we make something totally understandable, in other words, if we include every little detail and bit of context, it loses its discoverability.

但我们也可能走向另一个极端。如果我们让某样东西完全易懂,换句话说,如果我们包含了每一个小细节和背景信息,它就会失去可发现性。

The example above is my notes on the task management software Jira. It has lots of context, making it highly understandable. But it’s not discoverable at all. It would probably take me a couple hours and tremendous mental effort to read through this note and remember enough context to decide whether or not it’s useful. The main points and key insights are hidden somewhere in the noise.

上面的例子是我对任务管理软件 Jira 的笔记。它包含大量上下文,使其非常易于理解。但它完全不可被发现。我可能需要花费几个小时和巨大的脑力来阅读这个笔记,并记住足够的上下文以决定它是否有用。主要观点和关键见解隐藏在噪音中的某个地方。

Getting the balance between compression and context right is not a trivial matter. When the time comes for Future You to decide whether or not to review this note, seconds count. Because Future You will likely be looking for a solution to a problem, not casual reading, they will be making snap decisions on a tight timeline. Faced with a wall of text of questionable value, they are unlikely to take the risk of committing time for review.

在压缩与上下文之间取得平衡并非易事。当未来的你需要决定是否回顾这条笔记时,每一秒都至关重要。因为未来的你很可能是在寻找问题的解决方案,而非随意阅读,他们将在紧迫的时间线上迅速做出决定。面对一堵价值存疑的文字墙,他们不太可能冒险投入时间去回顾。

This means that all the summarizing work your Past Self did on this note is wasted. It didn’t pay off back then, and it doesn’t pay off in the future. You successfully sent a packet of information forward through time, but not in a state where it could survive the journey.

这意味着你的过去自我在这条笔记上所做的所有总结工作都白费了。它当时没有回报,未来也不会有回报。你成功地将一包信息发送到了未来,但它并未处于能够完好无损地完成这段旅程的状态。

Opportunistic compression

机会性压缩

I’ve found that most people do just fine on the context side of the equation. We know how to take exhaustive notes on a book, a presentation, or a class.

我发现大多数人在处理情境方面都做得很好。我们知道如何对一本书、一次演讲或一堂课做详尽的笔记。

Progressive Summarization focuses therefore on rebalancing the equation. It is a method for opportunistic compression — summarizing and condensing a piece of information in small spurts, spread across time, in the course of other work, and only doing as much or as little as the information deserves.

渐进式总结因此侧重于重新平衡这一等式。它是一种机会性压缩的方法——在其他工作的过程中,分小段时间对信息进行总结和浓缩,且仅根据信息本身的价值来决定压缩的程度。

If you remember, compression is a means to improving discoverability. So our design challenge when creating a note is:

如果你还记得,压缩是提高可发现性的一种手段。因此,我们在创建笔记时的设计挑战是:

“How do I make what I’m consuming right now easily discoverable for my future self?”

“如何让我现在消费的内容容易被未来的自己发现?”

This isn’t an easy question to answer, because you have no idea what Future You remembers, is interested in, or is working on. You have to summarize the note without knowing what it will be used for. It is general purpose summarization, a much greater challenge than extracting takeaways for just one specific project.

这个问题不容易回答,因为你不知道未来的你会记住什么、对什么感兴趣或在做什么。你必须在不知道笔记将用于何处的情况下进行总结。这是一种通用目的的总结,比仅为某个特定项目提取要点要更具挑战性。

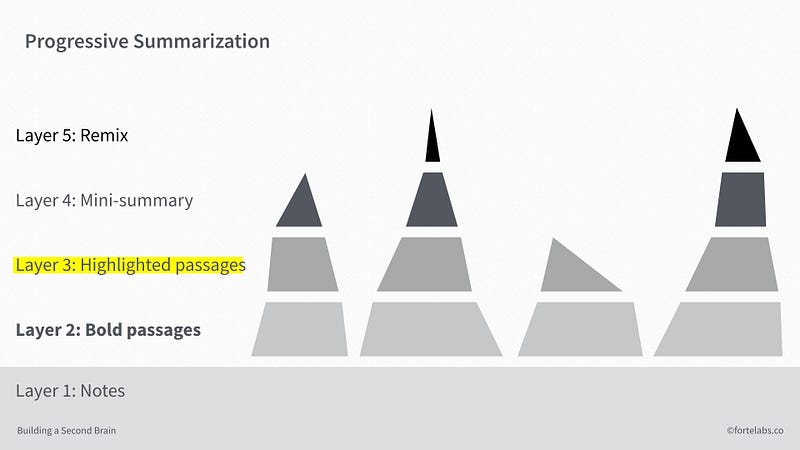

Progressive Summarization works in “layers” of summarization. Layer 0 is the original, full-length source text.

渐进式总结通过“层次”进行总结。第 0 层是原始的完整源文本。

Layer 1 is the content that I initially bring into my note-taking program. I don’t have an explicit set of criteria on what to keep. I just capture anything that feels insightful, interesting, or useful.

第一层是我最初带入笔记程序的内容。我没有明确的标准来决定保留什么。我只是捕捉任何感觉有洞察力、有趣或有用的内容。

This can include virtually any type of media, but for this article I will focus on text. There are many ways of doing this:

这几乎可以包括任何类型的媒体,但在本文中,我将重点讨论文本。实现这一点的方法有很多:

- Copy a paragraph of text from a PDF I’m reading, and paste it into the Evernote menu bar helper

从我正在阅读的 PDF 中复制一段文本,并将其粘贴到 Evernote 菜单栏助手中 - Type my random thoughts into a new note on the Evernote mobile app

在 Evernote 移动应用中输入我的随机想法到新笔记 - Dropping a Word document onto the Evernote icon in the dock on my Mac, which adds it to a note as an attachment

将 Word 文档拖放到我 Mac 上 Dock 中的 Evernote 图标上,即可将其作为附件添加到笔记中 - Downloading all my Kindle highlights from a book using Bookcision, and then copying and pasting them into a new note

使用 Bookcision 下载我 Kindle 中一本书的所有标注,然后将它们复制粘贴到一个新笔记中 - Forward an email with useful information to my personal import address, which automatically imports the whole email to a note

将包含有用信息的电子邮件转发到我的个人导入地址,该地址会自动将整个电子邮件导入为笔记 - Highlight the best passages of an online article using the web highlighter Liner, which exports directly to Evernote

使用网页高亮工具 Liner 突出显示在线文章的最佳段落,该工具可直接导出至 Evernote

The examples above are from my recommended program Evernote (iOS, Android, Mac, Windows, browsers), but all the major note-taking platforms support the above functionality in one way or another: Bear (Mac and iOS), Simplenote (iOS, Android, Mac, Windows, Linux), Microsoft OneNote (iOS, Android, Mac, Windows), and Google Keep (browsers, iOS, Android).

上述示例来自我推荐的程序 Evernote(iOS、Android、Mac、Windows、浏览器),但所有主要的笔记平台都以某种方式支持上述功能:Bear(Mac 和 iOS)、Simplenote(iOS、Android、Mac、Windows、Linux)、Microsoft OneNote(iOS、Android、Mac、Windows)和 Google Keep(浏览器、iOS、Android)。

Layer 1 is the starting point of Progressive Summarization, like the bedrock on which everything else is built:

第 1 层是渐进式总结的起点,如同构建一切的基石:

Layer 2 is the first round of true summarization, in which I bold only the best parts of the passages I’ve imported. Again, I have no explicit criteria. I look for keywords, key phrases, and key sentences that I feel represent the core or essence of the idea being discussed.

第二层是真正的第一轮总结,在这一层中,我只对我导入的段落中最好的部分进行加粗。同样,我没有明确的标准。我寻找那些我认为代表了所讨论思想核心或精髓的关键词、关键短语和关键句子。

I do this bolding layer at a later time, when I’m already reviewing this note anyway. I’m essentially using the attention I’m already spending for a dual purpose: to “buy” the information I need for the project at hand, and also to summarize the note for future use. If you have to pay attention to something, it comes in handy to be able to double-spend.

我在稍后的时间进行这一加粗层操作,那时我已经在回顾这条笔记了。我基本上是在利用已经投入的注意力实现双重目的:既为手头的项目“购买”所需信息,又为未来使用总结笔记。如果你必须关注某件事,能够双重利用这份注意力会非常方便。

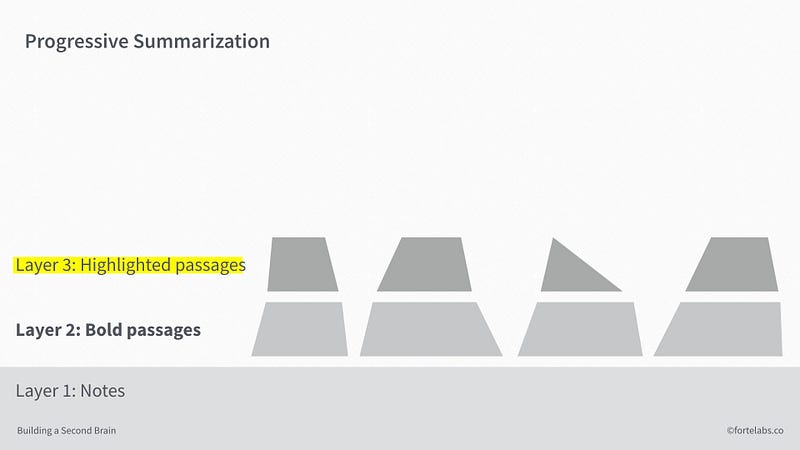

For Layer 3, I switch to highlighting, so I can make out the smaller number of highlighted passages among all the bolded ones. This time, I’m looking for the “best of the best,” only highlighting something if it is truly unique or valuable. And again, I’m only adding this third layer when I’m already reviewing the note anyway.

对于第三层,我转向高亮显示,这样我就能在所有加粗的段落中辨认出较少的高亮部分。这次,我寻找的是“精华中的精华”,只有当内容真正独特或具有价值时,才会进行高亮。同样,我仅在已经审阅笔记的情况下添加这第三层。

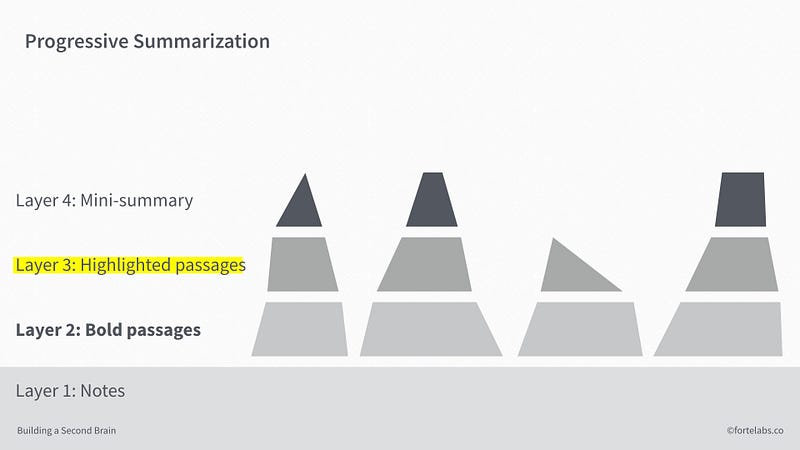

For Layer 4, I’m still summarizing, but going beyond highlighting the words of others, to recording my own. For a small number of notes that are the most insightful, I summarize layers 2 and 3 in an informal executive summary at the top of the note, restating the key points in my own words.

对于第四层,我仍在总结,但不仅仅是突出他人的话语,而是记录我自己的见解。对于少数最具洞察力的笔记,我在笔记顶部以非正式的执行摘要形式总结第二层和第三层,用自己的话重述关键点。

Note that all the previous layers are preserved in context, giving you the freedom to leave things out without worrying that you’ll lose them. Summarization is risky — you may be making the wrong decision about what’s important. But with the safety net of multiple layers of preserved notes, you can strike out decisively on daring intellectual expeditions.

请注意,所有之前的层次都保留在上下文中,让您可以自由地省略内容,而不用担心会丢失它们。总结是有风险的——您可能会对重要内容做出错误的判断。但有了多层保留笔记的安全网,您就可以在勇敢的智力探索中果断出击。

And finally, for a tiny minority of sources, the ones that are so powerful and exciting I want them to become part of how I think and work immediately, I remix them. After pulling them apart and dissecting them from every angle in layers 1–4, I add my own personality and creativity and turn them into something else.

最后,对于极少数资源,那些如此强大且令人兴奋以至于我希望它们立即成为我思考和工作方式的一部分的资源,我会对它们进行混音。在通过第 1 至 4 层将它们拆解并从各个角度剖析后,我会加入自己的个性和创造力,将它们转化为别的东西。

This could include a blog post interpreting, critiquing, or extending the argument an author is making, such as in Strategically Constrained, The Inner Game of Work, and Supersizing the Mind.

这可能包括一篇博客文章,解释、批评或扩展作者在《战略约束》、《工作的内在游戏》和《超级心智》等书中提出的论点。

But it doesn’t have to be difficult or time-consuming. It could even be…(gasp) fun! Making a sketch, designing a slide, recording a short video on your phone, and sharing on social media are all forms of wrestling deeply with information.

但这不必是困难或耗时的。它甚至可以是…(惊讶)有趣的!绘制草图、设计幻灯片、用手机录制短视频并在社交媒体上分享,都是深入处理信息的形式。

我写的关于《丰田套路》一书的第一条推文风暴

In Part II, we’ll look at some examples of Progressive Summarization in action.

在第二部分中,我们将看一些渐进式总结的实际示例。

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

关注我们,获取关于生产力和在 X、Facebook、Instagram、LinkedIn 和 YouTube 上构建第二大脑的最新动态和见解。如果您已准备好开始构建您的第二大脑,请获取这本书,学习经过验证的方法来组织您的数字生活并释放您的创造潜力。

- Posted in Attention, Building a Second Brain, Curation, Flow, How-To Guides, Note-taking, Workflow

发布于 注意力,构建第二大脑,策展,心流,操作指南,笔记,工作流程 - On

2017 年 12 月 27 日 - BY Tiago Forte