Why can’t we read anymore?

为什么我们不能再读书了?

Or, can books save us from what digital does to our brains?

或者,书籍可以让我们免受数字化对大脑的影响吗?

Last year, I read four books.

去年,我读了四本书。

The reasons for that low number are, I guess, the same as your reasons for reading fewer books than you think you should have read last year: I’ve been finding it harder and harder to concentrate on words, sentences, paragraphs. Let alone chapters. Chapters often have page after page of paragraphs. It just seems such an awful lot of words to concentrate on, on their own, without something else happening. And once you’ve finished one chapter, you have to get through another one. And usually a whole bunch more, before you can say finished, and get to the next. The next book. The next thing. The next possibility. Next next next.

我想,这个数字如此低的原因与你去年读的书比你认为应该读的书少的原因是一样的:我发现越来越难集中精力在单词、句子和段落上。更不用说章节了。章节通常有一页又一页的段落。似乎有太多的单词需要专注于它们自己,而没有其他事情发生。一旦你读完一章,你就必须读完另一章。通常还有一大堆,然后你才能说完成并进入下一个。下一本书。接下来的事情。下一个可能。下一个下一个。

I am an optimist 我是一个乐观主义者

Still, I am an optimist. Most nights last year, I got into bed with a book — paper or e — and started. Reading. Read. Ing. One word after the next. A sentence. Two sentences.

尽管如此,我还是一个乐观主义者。去年的大多数晚上,我都会拿着一本书(纸质书或电子书)上床睡觉,然后开始阅读。阅读。读。英格。一字接着一字。一句话。两句话。

Maybe three. 也许三个。

And then … I needed just a little something else. Something to tide me over. Something to scratch that little itch at the back of my mind— just a quick look at email on my iPhone; to write, and erase, a response to a funny Tweet from William Gibson; to find, and follow, a link to a good, really good, article in the New Yorker, or, better, the New York Review of Books (which I might even read most of, if it is that good). Email again, just to be sure.

然后……我只需要一些别的东西。有什么可以让我渡过难关。一些可以缓解我内心深处的小痒的东西——只需在我的 iPhone 上快速浏览一下电子邮件即可;写下并删除对威廉·吉布森的一条有趣推文的回应;找到并关注《纽约客》或更好的《纽约书评》上一篇好文章的链接(我什至可能会读大部分,如果它那么好的话)。再次发送电子邮件,只是为了确定。

I’d read another sentence. That’s four sentences.

我又读了一句话。就这四句话。

Smokers who are the most optimistic about their ability to resist temptation are the most likely to relapse four months later, and overoptimistic dieters are the least likely to lose weight. (Kelly McGonigal: The Willpower Instinct)

对自己抵抗诱惑的能力最乐观的吸烟者四个月后最有可能复吸,而过度乐观的节食者则最不可能减肥。 (凯利·麦格尼格尔:意志力本能)

It takes a long time to read a book at four sentences per day.

每天四句话读一本书需要很长时间。

And it’s exhausting. I was usually asleep halfway through sentence number five.

这很累。我通常读到第五句就睡着了。

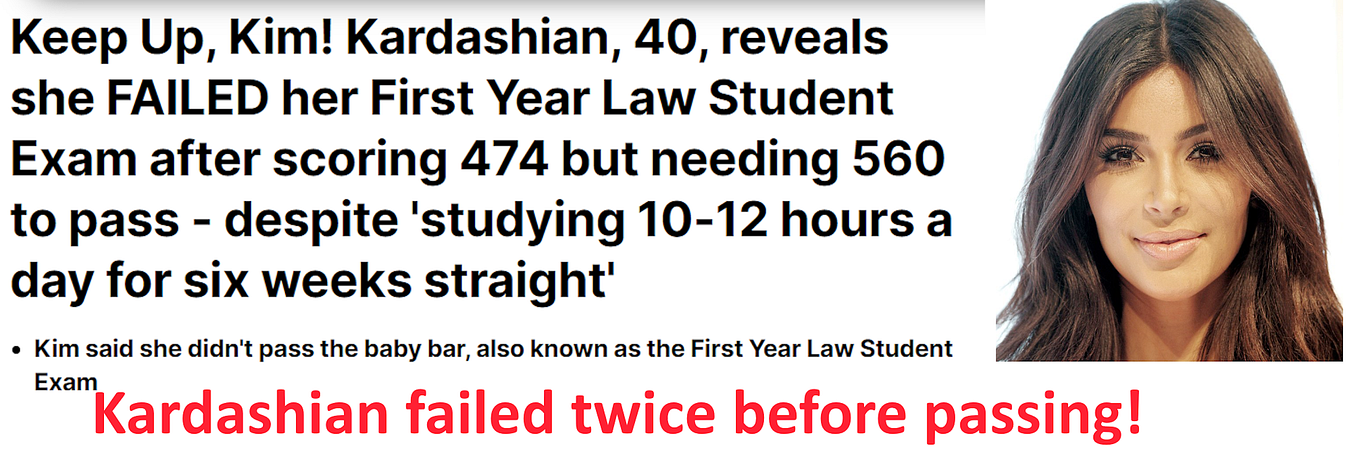

I’ve noticed this pattern of behaviour for a while now, but I think last year’s completed book tally was as low as it has ever been. It was dispiriting, most deeply so because my professional life revolves around books: I started LibriVox (free public domain audiobooks), and Pressbooks (an online platform for making print and ebooks), and I co-edited a book about the future of books.

我注意到这种行为模式已经有一段时间了,但我认为去年完成的图书数量与以往一样低。这令人沮丧,最令人沮丧的是,因为我的职业生活围绕着书籍:我创办了LibriVox (免费公共领域有声读物)和Pressbooks (制作印刷品和电子书的在线平台),并且我共同编辑了一本关于书籍未来的书。

I’ve dedicated my life one way or another to books, I believe in them, yet, I wasn’t able to read them.

我以某种方式将我的一生奉献给了书,我相信它们,然而,我无法阅读它们。

I’m not alone. 我并不孤单。

When the people at the New Yorker can’t concentrate long enough to listen to a song all the way through, how are books to survive?

当《纽约客》的人们无法集中足够的时间从头到尾听一首歌时,书籍如何生存?

I heard an interview on the New Yorker podcast recently, the host was interviewing writer and photographer, Teju Cole.

最近我在《纽约客》播客上听到一个采访,主持人正在采访作家兼摄影师泰朱·科尔。

Host: 主持人:

One of the challenges in culture now is to, say, listen to a song all the way through, we’re all so distracted, are you still able to kind of give deep attention to things, are you able to sort of engage in culture that way?”

现在文化中的挑战之一是,比如说,从头到尾听一首歌,我们都很心烦意乱,你是否仍然能够对事物给予深度关注,你是否能够参与文化那样吗?Teju Cole: 特朱·科尔:

“Yes, very much so.” “是的,非常如此。”

When I heard this, I felt like hugging the host. He couldn’t even listen to a song all the way through, before getting distracted. Imagine what his bedside pile of books does to him.

听到这句话,我真想抱抱楼主。他甚至无法听完一首歌,然后就分心了。想象一下床边的一堆书对他有什么影响。

I also felt like hugging Teju Cole. It’s people like Mr. Cole who give us hope that someone will be left to teach our children how to read books.

我也想拥抱泰朱·科尔。正是像科尔先生这样的人给了我们希望,希望有人能教我们的孩子如何读书。

Dancing to distraction 跳舞分散注意力

What was true of my problems reading books — the unavoidable siren call of the digital hit of new information — was true in the rest of my life as well.

我读书时遇到的问题是真实的——新信息的数字冲击不可避免的诱惑——在我的余生中也是如此。

My two-year old daughter, dance recital. Pink tutu. Cat ears on her head. Along with five other two-year-olds, in front of a crowd of 75 parents and grandparents, these little toddlers put on a show. You can imagine the rest. You’ve seen these videos on Youtube, maybe I have shown you my videos. The cuteness level was extreme, a moment that defines a certain kind of parental pride. My daughter didn’t even dance, she just wandered around the stage, looking at the audience with eyes as wide as a two-year old’s eyes starting at a bunch of strangers. It didn’t matter that she didn’t dance, I was so proud. I took photos, and video, with my phone.

我两岁的女儿,舞蹈表演。粉色芭蕾舞短裙。头上长着猫耳朵。这些小孩子与另外五个两岁的孩子一起,在 75 名父母和祖父母面前表演了一场表演。剩下的你可以想象。您已经在 Youtube 上看过这些视频,也许我已经向您展示了我的视频。可爱程度达到了极致,这一刻定义了某种父母的自豪感。我女儿甚至没有跳舞,她只是在舞台上走来走去,用两岁孩子的眼睛睁大眼睛看着观众,看着一群陌生人。她不跳舞没关系,我很自豪。我用手机拍了照片和视频。

And, just in case, I checked my email. Twitter. You never know.

而且,为了以防万一,我检查了我的电子邮件。叽叽喳喳。你永远不知道。

I find myself in these kinds of situations often, checking email or Twitter, or Facebook, with nothing to gain except the stress of a work-related message that I can’t answer right now in any case.

我发现自己经常处于这种情况下,查看电子邮件、推特或脸书,除了收到与工作相关的信息而感到压力之外,什么也得不到,而我现在无论如何都无法回复。

It makes me feel vaguely dirty, reading my phone with my daughter doing something wonderful right next to me, like I’m sneaking a cigarette.

当我的女儿在我旁边做一些美妙的事情时,我会觉得有点肮脏,就像我偷偷地抽烟一样。

Or a crack pipe. 或者是有裂纹的管道。

One time I was reading on my phone while my older daughter, the four-year-old, was trying to talk to me. I didn’t quite hear what she had said, and in any case, I was reading an article about North Korea. She grabbed my face in her two hands, pulled me towards her. “Look at me,” she said, “when I’m talking to you.”

有一次,我正在看手机,而我四岁的大女儿正试图和我说话。我没听清楚她说了什么,无论如何,我正在读一篇关于朝鲜的文章。她用两只手抓住我的脸,把我拉向她。 “当我和你说话时,”她说,“看着我。”

She is right. I should.

她是对的。我应该。

Spending time with friends, or family, I often feel a soul-deep throb coming from that perfectly engineered wafer of stainless steel and glass and rare earth metals in my pocket. Touch me. Look at me. You might find something marvellous.

与朋友或家人共度时光时,我经常会从口袋里那块由不锈钢、玻璃和稀土金属制成的完美设计的晶片中感受到灵魂深处的悸动。触摸我。看着我。你可能会发现一些奇妙的东西。

This sickness is not limited to when I am trying to read, or once-in-a-lifetime events with my daughter.

这种病不仅限于我尝试阅读时,或与我女儿发生的千载难逢的事件。

At work, my concentration is constantly broken: finishing writing an article (this one, actually), answering that client’s request, reviewing and commenting on the new designs, cleaning up the copy on the About page. Contacting so and so. Taxes.

在工作中,我的注意力不断被打破:写完一篇文章(实际上是这篇文章),回答客户的要求,审查和评论新设计,清理“关于”页面上的副本。联系某某。税收。

All these tasks critical to my livelihood, get bumped more often than I should admit by a quick look at Twitter (for work), or Facebook (also for work), or an article about Mandelbrot sets (which, just this minute, I read).

所有这些对我的生计至关重要的任务,通过快速查看 Twitter(工作)或 Facebook(也用于工作)或一篇关于曼德尔布罗特集的文章(就在这一分钟,我读到了)。

Email, of course, is the worst, because email is where work happens, and even if it’s not the work you should be doing right now it may well be work that’s easier to do than what you are doing now, and that means somehow you end up doing that work instead of whatever you are supposed to be working on now. And only then do you get back to what you should have been focusing on all along.

当然,电子邮件是最糟糕的,因为电子邮件是工作发生的地方,即使这不是您现在应该做的工作,它也可能是比您现在正在做的更容易做的工作,这意味着您以某种方式最终会做那项工作,而不是你现在应该做的任何事情。只有这样你才能回到你应该一直关注的事情上。

Dopamine and digital 多巴胺和数字

It turns out that digital devices and software are finely tuned to train us to pay attention to them, no matter what else we should be doing. The mechanism, borne out by recent neuroscience studies, is something like this:

事实证明,数字设备和软件经过精心调整,可以训练我们集中注意力,无论我们还应该做什么。最近的神经科学研究证实,其机制是这样的:

- New information creates a rush of dopamine to the brain, a neurotransmitter that makes you feel good.

新信息会向大脑产生大量多巴胺,这是一种让你感觉良好的神经递质。 - The promise of new information compels your brain to seek out that dopamine rush.

新信息的承诺迫使你的大脑寻找多巴胺的激增。

With fMRIs, you can see the brain’s pleasure centres light up with activity when new emails arrive.

通过功能磁共振成像,您可以看到当新电子邮件到达时,大脑的快乐中心会活跃起来。

So, every new email you get gives you a little flood of dopamine. Every little flood of dopamine reinforces your brain’s memory that checking email gives a flood of dopamine. And our brains are programmed to seek out things that will give us little floods of dopamine. Further, these patterns of behaviour start creating neural pathways, so that they become unconscious habits: Work on something important, brain itch, check email, dopamine, refresh, dopamine, check Twitter, dopamine, back to work. Over and over, and each time the habit becomes more ingrained in the actual structures of our brains.

因此,您收到的每封新电子邮件都会给您带来大量的多巴胺。每一点多巴胺的涌入都会强化你大脑的记忆,即检查电子邮件会产生大量的多巴胺。我们的大脑被编程为寻找能给我们带来少量多巴胺的东西。此外,这些行为模式开始创建神经通路,使它们成为无意识的习惯:做一些重要的事情,大脑痒,检查电子邮件,多巴胺,刷新,多巴胺,检查推特,多巴胺,回去工作。一次又一次,这种习惯在我们大脑的实际结构中变得更加根深蒂固。

How can books compete? 书籍如何竞争?

Pleasing ourselves to death

取悦我们自己至死

There is a famous study of rats, wired up with electrodes on their brains. When the rats press a lever, a little charge gets released in part of their brain that stimulates dopamine release. A pleasure lever.

有一项著名的研究是对老鼠的大脑进行电极连接。当老鼠按下杠杆时,它们大脑的一部分会释放出一点电荷,刺激多巴胺的释放。一个快乐的杠杆。

Given a choice between food and dopamine, they’ll take the dopamine, often up to the point of exhaustion and starvation. They’ll take the dopamine over sex. Some studies see the rats pressing the dopamine lever 700 times in an hour.

如果在食物和多巴胺之间做出选择,他们会选择多巴胺,通常会导致精疲力尽和饥饿。他们会接受多巴胺而不是性。一些研究发现老鼠在一小时内按下多巴胺杠杆 700 次。

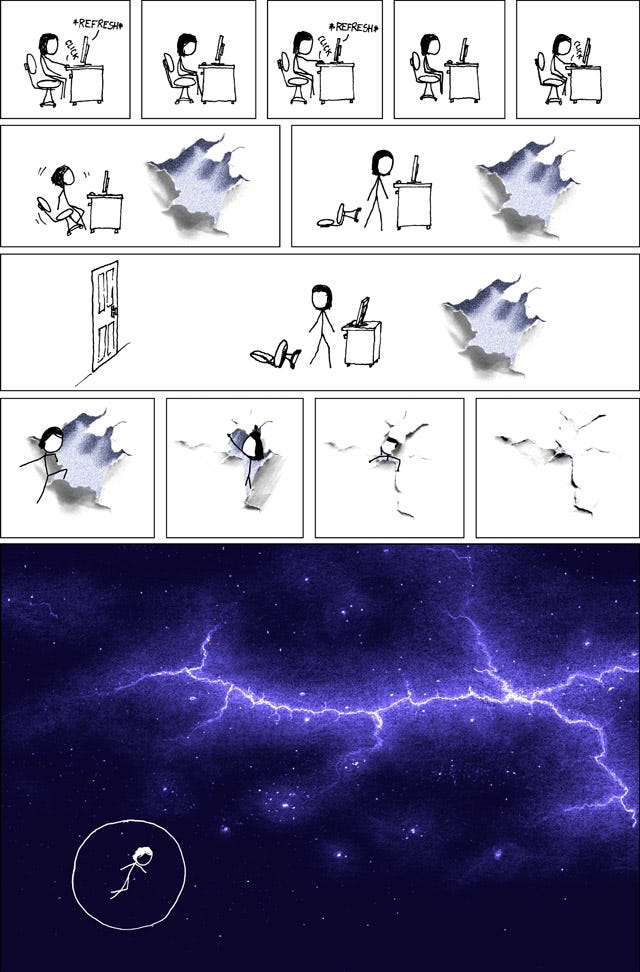

We do the same things with our email. Refresh. Refresh.

我们对电子邮件也做同样的事情。刷新。刷新。

There is no beautiful universe on the other side of the email refresh button, and yet it’s the call of that button that keeps pulling me out of the work I am doing, out of reading books I want to read.

电子邮件刷新按钮的另一边没有美丽的宇宙,但正是该按钮的调用不断将我从正在做的工作中拉出来,从阅读我想读的书中拉出来。

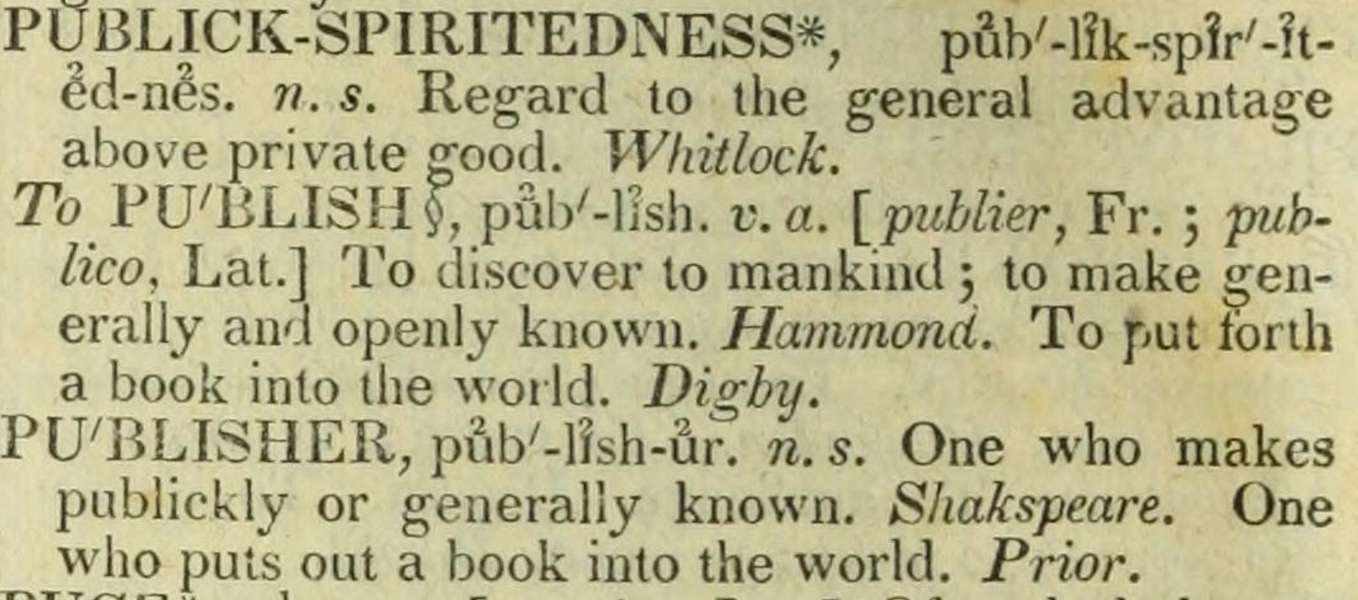

Why are books important? 为什么书籍很重要?

When I think back on my life, I can define a set of books that shaped me — intellectually, emotionally, spiritually. Books have always been an escape, a learning experience, a saviour, but beyond this, greater than this, certain books became, over time, a kind of glue that holds together my understanding of the world. I think of them as nodes of knowledge and emotion, nodes that knot together the fabric my self. Books, for me anyway, hold together who I am.

当我回想我的生活时,我可以定义一套在智力、情感和精神上塑造了我的书。书籍一直是一种逃避、一种学习经历、一种救世主,但除此之外,更重要的是,随着时间的推移,某些书籍成为了一种粘合我对世界的理解的粘合剂。我认为它们是知识和情感的节点,是将我的自我编织在一起的节点。无论如何,对我来说,书籍将我是谁联系在一起。

Books, in ways that are different to visual art, to music, to radio, to love even, force us to walk through another’s thoughts, one word at a time, over hours and days. We share our minds for that time with the writer’s. There is a slowness, a forced reflection required by the medium that is unique. Books recreate someone else’s thoughts inside our own minds, and maybe it is this one-to-one mapping of someone else’s words, on their own, without external stimuli, that give books their power. Books force us to let someone else’s thoughts inhabit our minds completely.

书籍,以不同于视觉艺术、音乐、广播、甚至爱情的方式,迫使我们在数小时甚至数天的时间里,一次一个字地了解他人的想法。我们与作者分享我们当时的想法。这种独特的媒介需要一种缓慢的、强制的反射。书籍在我们的脑海中再现了别人的想法,也许正是这种在没有外部刺激的情况下,对别人的话语进行一对一映射的方式赋予了书籍力量。书籍迫使我们让别人的想法完全占据我们的头脑。

Books are not just transferrers of knowledge and emotion, but a special kind of tool that flattens one self into another, that enable the trying-on of foreign ideas and emotions.

书籍不仅是知识和情感的传递者,而且是一种特殊的工具,可以将一个人变成另一个人,可以尝试外来的思想和情感。

This suppressing of the self is a kind of meditation too — and while books have always been important to me on their own (pre-digital) merits, it started to occur to me that “learning how to read books again,” might also be a way to start weaning my mind away from this dopamine-soaked digital detritus, this meaningless wash of digital information, which would have a double benefit: I would be reading books again, and I would get my mind back.

这种自我压抑也是一种冥想——虽然书籍因其自身(前数字化)的优点而对我来说一直很重要,但我开始意识到“重新学习如何读书”也可能是这是一种让我的思维摆脱这种被多巴胺浸泡的数字碎片、这种毫无意义的数字信息清洗的方法,这将有双重好处:我会再次读书,并且我会恢复我的思绪。

And, there are, often, beautiful universes to be found on the other side of the cover of a book.

而且,在书的封面的另一面常常可以找到美丽的宇宙。

The problems with digital stuff

数字产品的问题

Recent neuroscience confirms many of the things we sufferers of digital overload know innately. That successful multi-tasking is a myth. Multi-tasking makes us stupider. According to psychologist Glenn Wilson, the cognitive losses from multitasking are equivalent to smoking pot. (UPDATE: thanks to Liza Daly for pointing out that Glenn Wilson has publicly stated that this study was part of a paid PR gig, and misrepresented in the media. See: http://www.drglennwilson.com/Infomania_experiment_for_HP.doc)

最近的神经科学证实了我们这些数字过载患者天生就知道的许多事情。成功的多任务处理只是一个神话。多任务处理让我们变得更愚蠢。心理学家格伦·威尔逊 (Glenn Wilson) 认为,多任务处理造成的认知损失相当于吸大麻。 (更新:感谢Liza Daly指出 Glenn Wilson 公开表示这项研究是付费公关活动的一部分,并在媒体中进行了歪曲。请参阅: http://www.drglennwilson.com/Infomania_experiment_for_HP.doc )

This is bad for so many reasons: it makes us less effective at work, which means either we get less done, or have less time to spend doing other things, or both.

这很糟糕,原因有很多:它降低了我们的工作效率,这意味着要么我们完成的工作更少,要么花在做其他事情上的时间更少,或者两者兼而有之。

Being in a situation where you are trying to concentrate on a task, and an e-mail is sitting unread in your inbox, can reduce your effective IQ by 10 points. (The Organized Mind, by Daniel J Levitin)

当您试图集中精力完成某项任务时,收件箱中有一封电子邮件尚未阅读,您的有效智商可能会降低 10 点。 (丹尼尔·J·莱维汀《有组织的思维》)

It’s worse than that though, because this constant hopping from one thing to another is also exhausting.

但情况比这更糟糕,因为不断地从一件事跳到另一件事也让人筋疲力尽。

My least productive days, the days when I have spent the most time jumping between projects and emails and Twitter and whatever else, are also my most exhausting days. I used to think that my exhaustion was the cause of this lack of focus, but it turns out the opposite might be true.

我效率最低的日子,也就是我花最多时间在项目、电子邮件、推特和其他任何东西之间切换的日子,也是我最疲惫的日子。我曾经认为我的疲惫是导致注意力不集中的原因,但事实证明事实可能恰恰相反。

It takes more energy to shift your attention from task to task. It takes less energy to focus. That means that people who organize their time in a way that allows them to focus are not only going to get more done, but they’ll be less tired and less neurochemically depleted after doing it. (The Organized Mind, by Daniel J Levitin)

将注意力从一个任务转移到另一个任务需要更多的精力。集中精力需要更少的精力。这意味着,以一种能让他们集中注意力的方式安排时间的人不仅会完成更多工作,而且在完成工作后他们会感到不那么疲倦,神经化学物质的消耗也更少。 (丹尼尔·J·莱维汀《有组织的思维》)

The problem defined 问题定义

And so, the problem, more or less, is identified:

因此,问题或多或少已经确定:

- I cannot read books because my brain has been trained to want a constant hit of dopamine, which a digital interruption will provide

我无法读书,因为我的大脑已经被训练需要持续的多巴胺分泌,而数字中断会提供这种作用 - This digital dopamine addiction means I have trouble focusing: on books, work, family and friends

这种数字多巴胺成瘾意味着我很难集中注意力:书籍、工作、家人和朋友

Problem identified, or most of it. There is more.

已发现问题或大部分问题。还有更多。

Oh, and don’t forget about television

哦,别忘了电视

We live in a golden age of television, there is no doubt. The stuff being produced these days is very good. And there is a lot of it.

毫无疑问,我们生活在电视的黄金时代。这些天生产的东西非常好。而且有很多。

For the past couple of years, my evening routine has been a variation on: get home from work, exhausted. Make sure the girls have eaten. Make sure I eat. Get the girls to bed. Feel exhausted. Turn on the computer to watch some (neo-golden-age-era) television. Fiddle with work emails, and generally piddle around while that golden-age-era TV consumes 57% of my attention. Be bad at watching TV and bad at getting emails done. Go to bed. Try to read. Check email. Try to read again. Fall asleep.

在过去的几年里,我晚上的例行公事一直在变化:下班回家,筋疲力尽。确保女孩们已经吃饱了。保证我吃饭。让女孩们上床睡觉。感觉筋疲力尽。打开电脑看一些(新黄金时代)电视。摆弄工作电子邮件,通常闲逛,而黄金时代的电视占据了我 57% 的注意力。不擅长看电视,不擅长处理电子邮件。睡觉。尝试阅读。检查电子邮件。尝试再次阅读。睡着。

Those who read own the world, and those who watch television lose it. (Werner Herzog)

读书的人拥有世界,看电视的人失去世界。 (沃纳·赫尔佐格)

I don’t know if Werner Herzog is right, but I do know that I would never say about television — even the great stuff, of which there is plenty — what I say about books. There are no television shows that exist as nodes holding together my understanding of the world. My relationship to television is just not the same as it is to books.

我不知道沃纳·赫尔佐格是否正确,但我确实知道我永远不会像谈论书籍那样谈论电视——即使是伟大的东西,其中有很多。没有电视节目作为节点而存在,将我对世界的理解联系在一起。我与电视的关系与与书籍的关系不同。

And, so, a change 所以,改变

And so, starting in January, I started making some changes. The key ones are:

因此,从一月份开始,我开始做出一些改变。关键是:

- No more Twitter, Facebook, or article reading during the work day (hard)

工作日不再阅读 Twitter、Facebook 或文章(很难) - No reading of random news articles (hard)

不阅读随机新闻文章(难) - No smartphones or computers in the bedroom (easy)

卧室里没有智能手机或电脑(简单) - No TV after dinner (it turns out, easy)

晚饭后不看电视(事实证明,很简单) - Instead, go straight to bed and start reading a book — usually on an eink ereader (it turns out, easy)

相反,直接上床睡觉并开始读书——通常是使用 eink 电子阅读器(事实证明,很简单)

The shocking thing was how quickly my mind adapted to accommodate reading books again. I had expected to fight for that concentration — but I didn’t have to fight. With less digital input (no pre-bed TV, especially), extra time (no TV, again), and without a tempting digital device near at hand … there was time and space for my mind to settle into a book.

令人震惊的是我的大脑很快就适应了再次读书。我原以为要为这种专注而奋斗——但我不必奋斗。由于数字输入较少(尤其是睡前没有电视),额外的时间(再次没有电视),并且手边没有诱人的数字设备……我有时间和空间让我的思绪安定在书本上。

What a wonderful feeling it was.

那是一种多么美妙的感觉啊。

I am reading books now more than I have in years. I have more energy, and more focus than I’ve had for ages. I have not fully conquered my digital dopamine addiction, though, but it’s getting there. I think reading books is helping me retrain my mind for focus.

我现在看书的次数比以前多了。我比多年来更有活力、更专注。虽然我还没有完全克服我的数字多巴胺成瘾,但它正在实现。我认为读书可以帮助我重新训练注意力以集中注意力。

And books, it turns out, are still the same wonderful things they used to be. I can read them again.

事实证明,书籍仍然是和以前一样美妙的东西。我可以再读一遍。

Workday email, however, remains a problem. If you have suggestions for that, please let me know.

然而,工作日电子邮件仍然是一个问题。如果您对此有任何建议,请告诉我。

(By the way, I am starting a little email newsletter about books, reading and the technology that surrounds them both. I’ll aim to have something new every week or two. You can sign up here).

(顺便说一句,我正在开始写一篇关于书籍、阅读和围绕它们的技术的小型电子邮件通讯。我的目标是每周或每两周发布一些新内容。您可以在此处注册)。